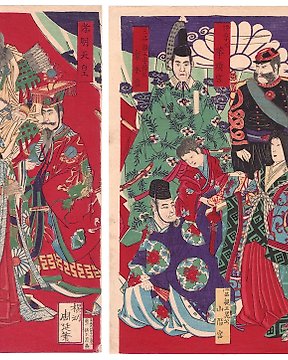

"Gli imperatori del Grande Giappone" 大日本皇統鏡 - 1881 - Toyohara Yōshū Chikanobu 楊洲周延 (1838-1912) - Japon - Période Meiji (1868–1912)

Nº 82177111

Nº 82177111

Title: Tsūzoku isoppu monogatari 通俗伊蘇普物語, volumes 1 and 6 (2 vol)

Date: 1875 (Meiji 8)

Artist: Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889)

Editor: Watanabe On 渡部温

6 volumes in modern case, fukurotoji (pouch binding), woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers, hanshibon format, no wood worms, no tears, impeccable condition.

Can be viewed here: https://pulverer.si.edu/node/389/title?search_api_views_fulltext=%E9%80%9A%E4%BF%97%E4%BC%8A%E8%98%87%E6%99%AE%E7%89%A9%E8%AA%9E&sort_by=search_api_relevance&sort_order=ASC

Dimensions: 22.4 x 15.1 x 0.7 cm

"The most famous edition in modern Japan was that of 1872–1875, entitled Tsūzoku Isoppu Monogatari

[Aesop’s fables for all]. The translation of two hundred and twenty-seven fables included in this six-volume edition was done from English by On Watanabe (1837–1898), a progressive activist and educator of the Japanese Enlightenment, the teacher of English in a very progressive school at that time (Numazu Heigakkō). The first five volumes of Aesop’s Fables for All were based on the English translation of Aesop’s Fables

done by Thomas James and published in 1863 by John Murray in London. That book was brought to Japan in 1868 by another famous educator and writer, Masakazu Toyama, who was then in England on a scholarship. The sixth volume was based on Three Hundred Aesop’s Fables translated by Flyer Townsend in London, as well as on premodern editions of Isopo Monogatari . It was a completely newtranslation, compared with the previous ones which had been based on texts from the Edo period. The epochal significance of this edition, so famous in Japan, consisted in using simple, everyday language in the translation, just like the sixteenth-century missionary translations. Watanabe introduced a completely modern style of translation using the spoken language, which was a phenomenon at a time when literature was still styled on the difficult, Chinese model of writing (so-called kanbun). Watanabe chose women and childrenas the main addressees of the fables; not only from the cities, but also from the provinces, which had been mentioned in the introduction of his book."

Each volume was also enriched with illustrations by well-known masters of painting and woodcuts, such as Kyosai Kawanabe, who painted with the vigorous line of the Kanōschool; Kōson Sakaki, famous for his sketches; and Bainan Fujisawa

--------------- from Aesop’s Fables in Japanese Literature for Children:Classical Antiquity and Japan, Beata Kubiak Ho-Chi

Shipping insured and express by DPD, FedEx and UPS, reaching anywhere in EU and US in 4-6 days.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One more quote, the history of Aesop in Japan is fascinating:

"When in the very first year of the Meiji period Toyama Masakazu 外山正一 (1848–1900) returned from his studies in England, he brought with him a copy of a modern version of Aesop’s Fables, written by the reverend Thomas James and first published in London by John Murray in 1848. This was translated into Japanese by the English scholar and entrepreneur Watanabe On 渡部温 (18371898). Watanabe’s Tsūzoku Isoppu monogatari 通俗伊蘇普物語 (A Popularized Aesop’s Tales) was published in 1872 in a woodblock edition. Its illustrations were reworkings of the original illustrations by John Tenniel by, among others, the wellknown painter Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831–1889). Inspired by Watanabe’s 25 A Forgotten Aesop translation, Kyōsai in 1873 began publishing a lavishly colored nishiki-e 錦絵 print series on the theme of “Among the tales of Aesop” (Isoppu monogatari no uchi 伊蘇普物語之内).3 Watanabe’s book quickly became a bestseller, with reprints set in type, and was used as a textbook in the new primary school system that was established in that very same year. Several versions of Aesop’s fables were to follow, creating an ‘Aesop boom’ and establishing the tales as one of the earliest Meiji absorptions of European literature. It is fairly safe to claim that Meiji’s interest in Western literature began large-scale with Aesop’s fables. Few in Japan at the time realized that by 1872 Aesop’s fables had already been present in Japan for nearly three centuries. Today, it is fairly common knowledge that as part of their enterprise in Japan, the Jesuits established a printing center with a press that was brought to Kazusa 加津佐, Kyushu, in 1590, and which from 1592 onwards was located on the island of Amakusa 天草, not too far from Nagasaki, where the printing operation was conducted under the protection of its Christian daimyō.4 In 1593, the Jesuit mission press printed a Japanese translation of Aesop’s fables, type-set with Roman letters in a transcription system that the Jesuits had developed, titled ESOPONO FABULAS, “translated from the Latin to Japanese speech” (Latinuo vaxite Nippon no cuchi to nasu mono nari).5 In addition to its professed aim to introduce European moral ideas, an important goal of this publication seems to have been to help Europeans learn the Japanese language: “Not only is this [book] truly dependable when learning the Japanese language, but it can also be an instrument in teaching people the right way.” (Core macotoni Niponno cotoba qeicono tameni tayorito naru nominarazu, yoqi michiuo fitoni voxiye cataru tayoritomo narubeqi mono nari).6 What this targeting of non-Japanese readers meant for the circulation of this early Japanese translation of the fables is an open question; in any case, the fables ultimately did reach a Japanese readership."

Comment acheter sur Catawiki ?

1. Découvrez des objets d’exception

2. Faites la meilleure offre

3. Effectuez un paiement sécurisé