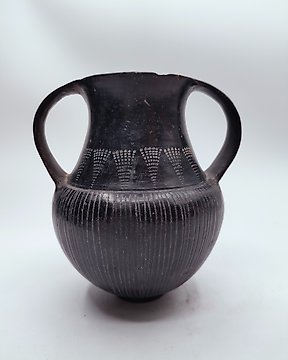

Etruscan Bucchero Nero Amphore décorée. Licence d'importation espagnole.

Nº 82680415

Nº 82680415

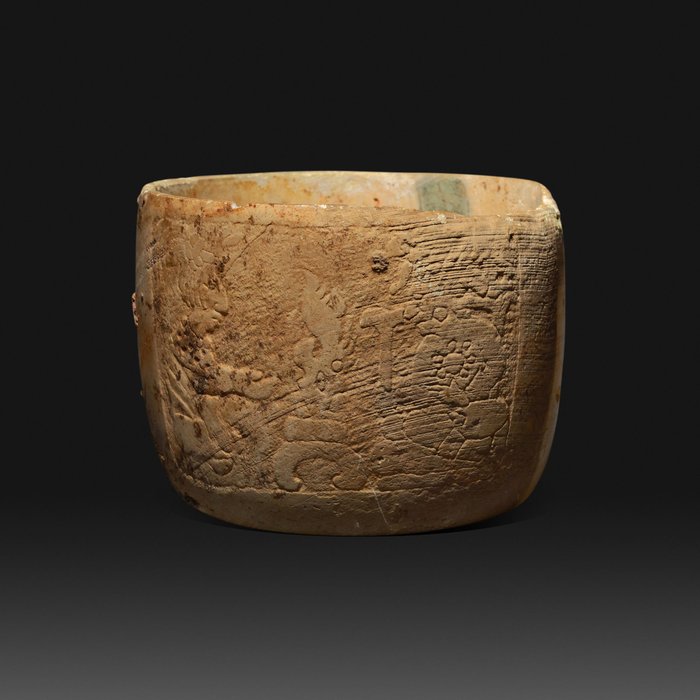

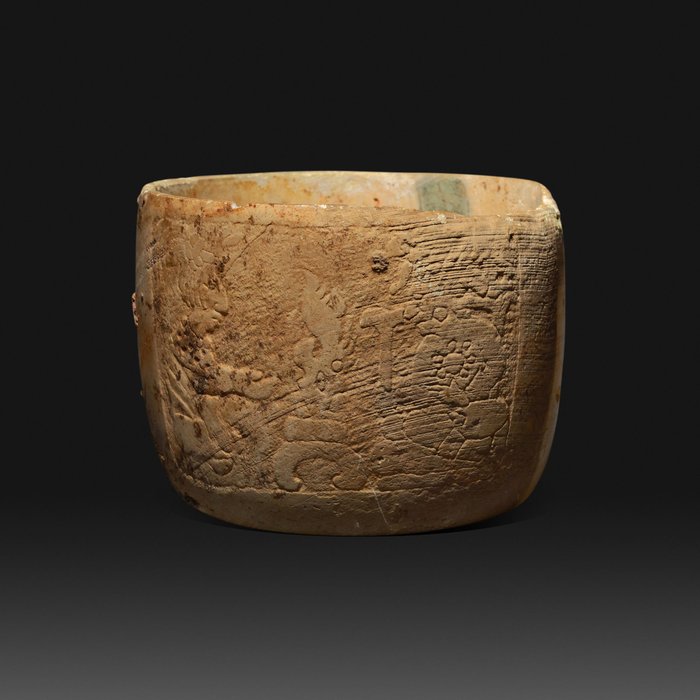

Cylindrical Container with Figurative Reliefs.

Mayan, Classic Period, 600 - 900 AD.

MATERIAL: Alabaster (thecali stone).

DIMENSIONS: Diameter 12 cm. 9.5 cm height.

PROVENANCE:

- Antique collection Le Corneur, France. Rémy Audoin, 1967.

- Arts des Amériques Gallery, circa 1980.

- Collection of Michel Vinaver, French writer and playwright (Paris, 1927 -2022).

- To his children, Anouk, Barbara, Delphine and Ivan Vinaver, 2022.

- French art market,

CONDITION: In good condition, it has a vertical crack on one side up to the middle of the base. It presents two holes parallel to the crack, a sign of an old restoration of the time. Inside, traces of polychromy and stucco are preserved in the more translucent areas of the vase.

DESCRIPTION:

Cylindrical vessel with slightly curved walls and base, with a straight and narrow mouth, without a lip. It presents two pairs of parallel holes around an old crack, which show an old restoration with staples. Currently, marks of the roots of the plants that grew around the piece when it was buried can be seen, irregular and asymmetric shapes that enrich the texture of the vase. It is made of tecali stone, a type of travertine also known as Mexican onyx or alabaster, although it is a different mineral from Egyptian alabaster. The stone presents a translucent vein, of regular width, which was probably the reason why the artist chose this specific piece of tecali, given its prominence at an ornamental level: it forms a vertical line, perpendicular to the mouth, which crosses the base, dividing it in two halves and finally rises from the opposite end of the glass, forming a meander. A similar effect can be observed, obtained in this case with varnish or pigment, in the ceramic vase cataloged by Kerr as K623 (fig. 1). The formal importance of this vein is also reflected in the preserved remains of polychrome stucco, applied only to it and leaving the rest of the piece free.

In the case of this glass, the translucent vein could represent a snake, an animal of great importance within the Mayan religion; vehicle for contact with heavenly bodies, it was a symbol of death and resurrection. One of the most important serpents in Mayan mythology, the Vision Serpent, was considered the gate between the natural and supernatural worlds, and was therefore often depicted on ritual vessels, usually carved stone.

The glass is also decorated with a figurative scene that occupies approximately one third of its surface. It is worked in relief on two planes, and is framed by a smooth rectangular profile with rounded corners. It is a composition with two characters facing each other, usual to indicate dialogue, something that is also reflected in the conventional gestures of the hands (fig. 2). The formal style is synthetic: the background has been sunk, clearly delimiting the silhouettes of the characters, which are perfectly drawn. This linearity is repeated in the internal details of the figures, indicated by fine incisions. The schematism, however, is combined with a certain naturalism in the movement of the figures: slightly inclined heads, the position of an arm on the lap... One of the fundamental characteristics of Mayan figurative art was the search for naturalistic positions and compositions, dynamic, with bodies that rotate and elements that overlap, reaching between the 7th and 8th centuries a mastery unmatched by any other Mesoamerican culture. This search for naturalism was combined with a symbolic convention that never quite disappeared.

The figure on the left appears seated in profile to the right, with a headdress tied in the front, a pectoral ornament, and a skirt typical of Mayan art, which forms parallel folds at the base of the back and whose end falls over the top. the hip (fig. 3). The figure extends her right hand towards the center of the composition, where an altar with an inverted C-shaped base is located. A fire seems to be burning on it with what could be offerings, two rounded shapes represented within the flames. The representation of the fire is strange, asymmetrical and crested, which could indicate that it is not flames but rather the representation of a scepter of the type known as a flint eccentric (fig. 4).

On the right side is the second figure, seated facing forward with its head inclined towards the center of the composition, turned in profile to the left. With his legs crossed, he rests his left arm on his lap, pointing at his interlocutor with a clearly differentiated index finger, and extends his right, now lost due to erosion, towards the fire. She sports ankle, cheek and wrist ornaments, and a large headdress. On her chest she wears a medallion with a possibly solar motif, a central circle surrounded by six smaller ones. The character is seated on a throne, a symbol of authority; with seat, cushion and high, wide and open backrest, adorned with projections on both sides. The figure on the opposite side instead sits on a simple pedestal, indicating his inferior position relative to his companion, possibly a deity or ancestor.

The circle on the cheek (allusive to the fur of the jaguar) and the pendant of the supernatural character allow a possible identification with the god of corn (fig. 5), one of the most important of the Mayan pantheon. He was a benevolent deity who represented life, prosperity, and abundance. He could be considered the creator of the world, and he was also associated with the change of seasons. Likewise, the story of his death and rebirth was a central metaphor for the belief in the apotheosis of Maya kings. Identified as Hun-Hunahpu in the Popol Vuh, a compendium of Maya lore put down in writing in the 16th century, the maize god achieved cultural hero status during the Classic period.

The use of tecali, a precious material used to manufacture luxury and ritual objects, spread throughout Mesoamerica. The vases made of this stone are relatively rare, and for the most part they are painted, following the models of contemporary ceramic vases. Within the corpus of Mayan carved vessels, on the other hand, it is more common to find vessels made of this and other stones, although the majority will be ceramic. Among them, simple relief on two planes predominates, as in the case of the piece under study, with figurative motifs, inscriptions or geometric patterns, often combined (fig. 6). Some present compositions similar to that of this tecali stone vase, with one or more pairs of characters seated and facing each other, in an attitude of dialogue (fig. 7).

Mayan vases or cylinders are an inexhaustible source of information about their culture. They are a privileged support where they were able to masterfully capture their imaginary: they inform about the history and life of the elites, but, above all, they are an important element to learn about mythology; both the images of the gods and the myths, frequently accompanied by glyphs indicating the name of the person or god, which define the activity they are representing. Sometimes other types of inscriptions appear on Mayan vases, the so-called dedications, in which it is named who has paid for the making of the vase, for what purpose and, in some cases, the name of the author. In this way it is known which shape was used to contain which liquids; the concave and cylindrical containers were intended to store drinks inside to be consumed during the parties of the privileged classes —especially chocolate. These highly valuable containers were exchanged among themselves for diners or gift items. Even though they were of funerary origin, the vast majority were made to be used while still alive, although it was common for them to be taken to the grave, or similar ones, to include them in their trousseau.

Developed in an immense area that included Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, a large part of Mexico and the western zone of Honduras, the Mayan culture developed from the year 2000 B.C. approximately. What differentiates it from the rest of Mesoamerican cultures is the use of writing. In fact, it was probably the main tool for its extraordinary development, since it allowed distance communications and historical records; It encompassed not just one or two population centers, but dozens of cities and towns belonging to the same belief system, sharing the same culture.

In the Protoclassic Period (50 BC – 250 AD) the first stelae appear representing religious and power-related scenes, and the first pyramids are built. This is also the moment of the founding of Teotihuacán, whose culture exerted a notable influence on the Mayans, especially their cult of war. As Mesoamerica flourished during the Classic Period (AD 250-900), Maya cities prospered under a dynastic regime whose power was reflected in the numerous depictions of individual kings on stelae, accompanied by texts glorifying their reigns. Different dynasties emerged in the different cities, Tikal being probably the first to initiate wars of conquest against its neighbors, following the warlike ideology and technology promulgated by the Teotihuacans. The Mayan kings then began to record their victories, genealogies, and the passage of time on their monuments. By the beginning of the eighth century, the Maya aristocracy enjoyed wealth unparalleled until then, but lived in a time of continuous conflict between cities and kings. The population was growing rapidly, which also led to a rapid degradation of the natural environment, unable to produce enough food. By the end of the 8th century, and during the 9th, the so-called Mayan Collapse took place: the ceremonial precincts were abandoned and the population was drastically reduced. By the year 900, the Mayan domain had already been replaced by the new power: the Toltecs.

Complete Description

Cylindrical vessel with slightly curved walls and base, with a straight and narrow mouth, without a lip. It presents two pairs of parallel holes around an old crack, which show an old restoration with staples. Currently, marks of the roots of the plants that grew around the piece when it was buried can be seen, irregular and asymmetric shapes that enrich the texture of the vase. It is made of tecali stone, a type of travertine also known as Mexican onyx or alabaster, although it is a different mineral from Egyptian alabaster. The stone presents a translucent vein, of regular width, which was probably the reason why the artist chose this specific piece of tecali, given its prominence at an ornamental level: it forms a vertical line, perpendicular to the mouth, which crosses the base, dividing it in two halves and finally rises from the opposite end of the glass, forming a meander. A similar effect can be observed, obtained in this case with varnish or pigment, in the ceramic vase cataloged by Kerr as K623 (fig. 1). The formal importance of this vein is also reflected in the preserved remains of polychrome stucco, applied only to it and leaving the rest of the piece free.

In the case of this glass, the translucent vein could represent a snake, an animal of great importance within the Mayan religion; vehicle for contact with heavenly bodies, it was a symbol of death and resurrection. One of the most important serpents in Mayan mythology, the Vision Serpent, was considered the gate between the natural and supernatural worlds, and was therefore often depicted on ritual vessels, usually carved stone.

The glass is also decorated with a figurative scene that occupies approximately one third of its surface. It is worked in relief on two planes, and is framed by a smooth rectangular profile with rounded corners. It is a composition with two characters facing each other, usual to indicate dialogue, something that is also reflected in the conventional gestures of the hands (fig. 2). The formal style is synthetic: the background has been sunk, clearly delimiting the silhouettes of the characters, which are perfectly drawn. This linearity is repeated in the internal details of the figures, indicated by fine incisions. The schematism, however, is combined with a certain naturalism in the movement of the figures: slightly inclined heads, the position of an arm on the lap... One of the fundamental characteristics of Mayan figurative art was the search for naturalistic positions and compositions, dynamic, with bodies that rotate and elements that overlap, reaching between the 7th and 8th centuries a mastery unmatched by any other Mesoamerican culture. This search for naturalism was combined with a symbolic convention that never quite disappeared.

The figure on the left appears seated in profile to the right, with a headdress tied in the front, a pectoral ornament, and a skirt typical of Mayan art, which forms parallel folds at the base of the back and whose end falls over the top. the hip (fig. 3). The figure extends her right hand towards the center of the composition, where an altar with an inverted C-shaped base is located. A fire seems to be burning on it with what could be offerings, two rounded shapes represented within the flames. The representation of the fire is strange, asymmetrical and crested, which could indicate that it is not flames but rather the representation of a scepter of the type known as a flint eccentric (fig. 4).

On the right side is the second figure, seated facing forward with its head inclined towards the center of the composition, turned in profile to the left. With his legs crossed, he rests his left arm on his lap, pointing at his interlocutor with a clearly differentiated index finger, and extends his right, now lost due to erosion, towards the fire. She sports ankle, cheek and wrist ornaments, and a large headdress. On her chest she wears a medallion with a possibly solar motif, a central circle surrounded by six smaller ones. The character is seated on a throne, a symbol of authority; with seat, cushion and high, wide and open backrest, adorned with projections on both sides. The figure on the opposite side instead sits on a simple pedestal, indicating his inferior position relative to his companion, possibly a deity or ancestor.

The circle on the cheek (allusive to the fur of the jaguar) and the pendant of the supernatural character allow a possible identification with the god of corn (fig. 5), one of the most important of the Mayan pantheon. He was a benevolent deity who represented life, prosperity, and abundance. He could be considered the creator of the world, and he was also associated with the change of seasons. Likewise, the story of his death and rebirth was a central metaphor for the belief in the apotheosis of Maya kings. Identified as Hun-Hunahpu in the Popol Vuh, a compendium of Maya lore put down in writing in the 16th century, the maize god achieved cultural hero status during the Classic period.

The use of tecali, a precious material used to manufacture luxury and ritual objects, spread throughout Mesoamerica. The vases made of this stone are relatively rare, and for the most part they are painted, following the models of contemporary ceramic vases. Within the corpus of Mayan carved vessels, on the other hand, it is more common to find vessels made of this and other stones, although the majority will be ceramic. Among them, simple relief on two planes predominates, as in the case of the piece under study, with figurative motifs, inscriptions or geometric patterns, often combined (fig. 6). Some present compositions similar to that of this tecali stone vase, with one or more pairs of characters seated and facing each other, in an attitude of dialogue (fig. 7).

Mayan vases or cylinders are an inexhaustible source of information about their culture. They are a privileged support where they were able to masterfully capture their imaginary: they inform about the history and life of the elites, but, above all, they are an important element to learn about mythology; both the images of the gods and the myths, frequently accompanied by glyphs indicating the name of the person or god, which define the activity they are representing. Sometimes other types of inscriptions appear on Mayan vases, the so-called dedications, in which it is named who has paid for the making of the vase, for what purpose and, in some cases, the name of the author. In this way it is known which shape was used to contain which liquids; the concave and cylindrical containers were intended to store drinks inside to be consumed during the parties of the privileged classes —especially chocolate. These highly valuable containers were exchanged among themselves for diners or gift items. Even though they were of funerary origin, the vast majority were made to be used while still alive, although it was common for them to be taken to the grave, or similar ones, to include them in their trousseau.

Developed in an immense area that included Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, a large part of Mexico and the western zone of Honduras, the Mayan culture developed from the year 2000 B.C. approximately. What differentiates it from the rest of Mesoamerican cultures is the use of writing. In fact, it was probably the main tool for its extraordinary development, since it allowed distance communications and historical records; It encompassed not just one or two population centers, but dozens of cities and towns belonging to the same belief system, sharing the same culture.

In the Protoclassic Period (50 BC – 250 AD) the first stelae appear representing religious and power-related scenes, and the first pyramids are built. This is also the moment of the founding of Teotihuacán, whose culture exerted a notable influence on the Mayans, especially their cult of war. As Mesoamerica flourished during the Classic Period (AD 250-900), Maya cities prospered under a dynastic regime whose power was reflected in the numerous depictions of individual kings on stelae, accompanied by texts glorifying their reigns. Different dynasties emerged in the different cities, Tikal being probably the first to initiate wars of conquest against its neighbors, following the warlike ideology and technology promulgated by the Teotihuacans. The Mayan kings then began to record their victories, genealogies, and the passage of time on their monuments. By the beginning of the eighth century, the Maya aristocracy enjoyed wealth unparalleled until then, but lived in a time of continuous conflict between cities and kings. The population was growing rapidly, which also led to a rapid degradation of the natural environment, unable to produce enough food. By the end of the 8th century, and during the 9th, the so-called Mayan Collapse took place: the ceremonial precincts were abandoned and the population was drastically reduced. By the year 900, the Mayan domain had already been replaced by the new power: the Toltecs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- EVANS, S.T.; WEBSTER, D.L. Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. 2000.

- KERR, J. The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases. Kerr Associates. 1989.

- MILLER, M.; TAUBE, K. The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames & Hudson. 1997.

- MILLER, M. Maya Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson. 1999.

- SHARER, R.J.; TRAXLER, L.P. The Ancient Maya. Stanford University Press. 2006.

- THOMPSON, J.E.S. Maya History and Religion. University of Oklahoma Press. 1970.

PARALLELS:

Fig. 1 Vase with aquatic landscape and mythical animal. Maya, Late Classic period, A.D. 600-900, ceramic. Princeton University Art Museum (USA), inv. 2020.684. Kerr K623.

Fig. 2 Carved lintel with two supernatural characters. Maya, Late Classic period, A.D. 600-900, stone. Amparo Museum, Puebla (Mexico), inv. 52 22 MA FA 57PJ 1365.

Fig. 3 Relief with two characters conversing. Maya, Mexico, Late Classic period, A.D. 600-900, stucco and polychrome. Amparo Museum, Puebla (Mexico), inv. 52 22 MA FA 57PJ 1363.

Fig. 4 Flint eccentric. Maya, Late Classic period, A.D. 600-700, Flint. Metropolitan Museum, New York, inv. 1978.412.195.

Fig. 5 Representation of the maize god as a scribe on a codex-style vase. Maya, Classic period, A.D. 250-900, ceramic. Particular collection.

Fig. 6 Jug with representation of gods, inscriptions and geometric motifs. Maya, Protoclassic period, c. 50 BC – 50 AD, hardened limestone. Metropolitan Museum, New York, inv. 1999.484.3.

Fig. 7 Vase with pairs of characters (display). Maya, Classic period, A.D. 250-900, ceramic. Particular collection. Kerr K1120.

Notes:

- The piece includes authenticity certificate.

- The piece includes Spanish Export License (Passport for European Union) - If the piece is destined outside the European Union a substitution of the export permit should be requested, can take between 1-2 weeks maximum.

- The seller guarantees that he acquired this piece according to all national and international laws related to the ownership of cultural property. Provenance statement seen by Catawiki.

Comment acheter sur Catawiki ?

1. Découvrez des objets d’exception

2. Faites la meilleure offre

3. Effectuez un paiement sécurisé