Perfecto! :)

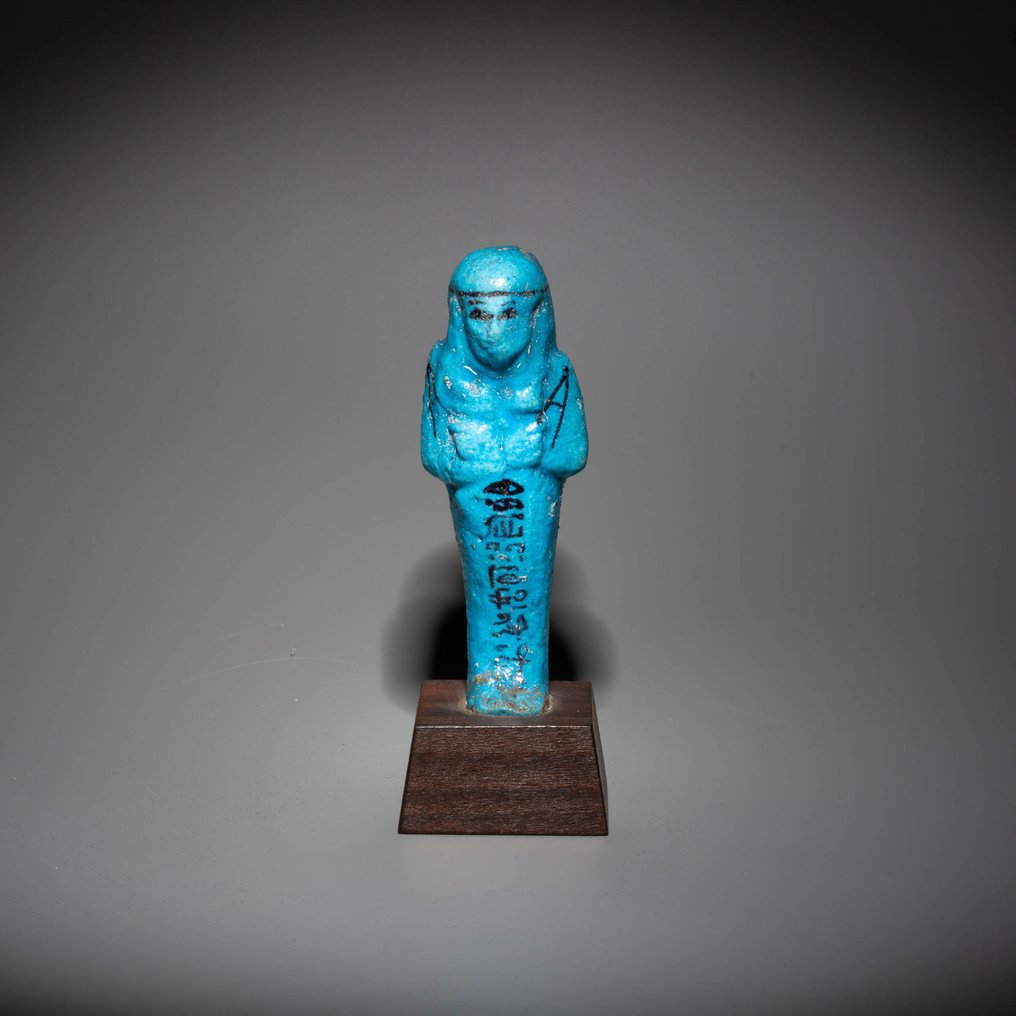

Vizualizați traducereaEgiptul Antic Faianță Shabti pentru supraveghetorul grânarelor, Djedkhonsu-iwf-ankh. 10,5 cm H. Intact. Licență de export

Nr. 85155383

Ushabti or Shabti Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh, the 'Overseer of Granaries',

- important shabti -

- nice blue color -

-museum quality-

The front has a vertical column of text: "The Osiris, overseer of granaries, Djedkhonsu-iwf-ankh, justified".

Ancient Egypt, Third Intermediate Period, 1070 - 650 BC

MATERIAL: Faience

DIMENSIONS: Height 10,5 cm without stand.

PROVENANCE: Private collection, France, 1970 - 1980. Excavated by Herbert Winlock at Deir el-Bahri.

CONDITION: Intact.

Museum quality ushabti figure, named Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh, the 'Overseer of Granaries', Egyptian faience, Deir el-Bahri, Egypt, Dynasty 21, Third Intermediate Period (1080-945 BC)

On the cover of the more than 1.100 pages book about shabtis from Luis Manuel de Araujo, Estatuetas funerárias Egípcias da XXI dinastia, a worker shabti from this series is printed on the cover, see photo. Several shabtis of this series were given to foreign musea by the Egyptian authorities and sold to private collectors at the end of the 19th century.

The iconography and purpose of the ushabtis seem to have been standardized from the late New Kingdom.

The statuette is in the form of a mummy, wrapped in a shroud and standing upright with both feet together. The hands are crossed on the chest and hold a pair of A-shaped hoes, tools necessary for agricultural work, and seed sack, painted in black. The ushabti wears a tripartite wig with locks of hair indicated by incised lines. The facial features are carefully modeled and suggest the individual portrait. The narrow tressed beard is attached under the chin.

The front has a vertical column of text: "The Osiris, overseer of granaries, Djedkhonsu-iwf-ankh, justified".

It was produced for a deceased man named "Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh" (whose tomb was excavated by Herbert Winlock at Deir el-Bahri). This name appears on other similar shabtis in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (E.9.1946 and E.10.1946), Kazan (15701), Lisbon (MNA E 99), Manchester, Moscow, New York (MMA 10.130.1063 a-d and 26.32.3), Toulouse and Winterthur (6780 (429)).

Ushabti were made from one original bi-valve mold. Once the two pieces were joined and the rough edges removed, and while the material was still moist, the details of the image were retouched and the columns were marked on which the hieroglyphs would be incised. This meant that each ushabti was unique, even though they had come from the same mold.

The material used for the creation of this ushabti is faience, composed of fine sand cemented with sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate extracted from natron. Fired at 950 degrees C, the mixture gives an enamel-like finish with the carbonates forming a vitreous surface. It was a simple procedure and therefore not costly. The green and blue tones were achieved by the addition of a few grams of copper oxide extracted from malachite or azurite. The red tones were achieved with iron oxide, the intense blues with cobalt, the black by mixing iron oxide and magnesium oxide with water. All that was needed was to paint the chosen details in the selected colour with a brush before the firing.

The Egyptian Afterlife was understood as a mirror of the real world, where both good and evil had their place. Those who were unfair or evil were punished for eternity, while the just enjoyed a comfortable existence travelling with the solar god. Even then, the deceased who were so blessed were still obliged to fulfil human responsibilities and needs, in the same way they had to in life. Their need to have food and drink in the Afterlife was a constant worry for them. If they were obliged to work in the Fields of Aaru, in the Realm of the Dead, and as members of a society which was a hierarchy governed by the gods, everyone – men and women, lords and servants, kings and queens – had to be willing to cultivate, sow and harvest the crops.

In the world of the living these basic tasks of production were carried out by the lower classes in society. To avoid this fate, Egyptians looked for a magic solution: they created one or more figures of themselves to be able to hand over to the emissaries of the reigning god, Osiris, when these called on the deceased to fulfil his obligations. These statuettes, placed amongst the grave goods in the tomb, were images which represented both the master and the servant.

They are known by the name of ushabtis, the term coming from sabty or shabty, derived from Sawab, the meaning of which corresponds to the Greek word “persea”, a sacred tree from whose wood the ancient Egyptians began to produce these funerary effigies. It was towards the Third Intermediate Period, in Dynasty XXI, around 1080 BC when they began to use the term wsbty, that is, “ushebty”. From then on the name “ushabti” derived from the verb wsb meaning “to answer” was used to name “he who answers”.

The use of ushabtis was incorporated into the burials in Ancient Egypt from the First Intermediate Period on. Their use grew during the Middle Kingdom, the time when the Egyptians began to write a spell in the Coffin Texts, number 472, so that the ushabtis would answer to the call: “The justified N. says ‘Oh ushabti, allotted to N, if N is summoned to do any work, or if a disagreeable task was asked of N as for any man for his duty, you are to say ‘I am here’. If N is called to watch over those who work there, ploughing the new fields to break the earth, or to ferry sand in a boat from east to west, you will say ‘I am here’. The justified N.”

This spell or utterance went on to be inscribed on ushabtis, and so in most cases, it appears there engraved. From the New Kingdom on, a great number of innovations were introduced. Examples with texts started to proliferate. Some of these were somewhat longer texts from Chapter VI in the Book of the Dead. Even so, in many cases the text simply indicates the name of the deceased, or a basic utterance, with the name of a family member or the posts that he held.

Ushabtis at first were made above all from wax, later from wood, and then towards the end of the Middle Kingdom they appeared in stone. From the New Kingdom on, the material par excellence was faience. We know they were produced in multiples thanks to moulds which have been preserved, and where in some cases, the engraved texts were unfinished, as the name of the owner was missing. The most popular form was that of the mummy until the introduction, towards the end of Dynasty XVIII, of figures decorated with everyday clothing. Many carried implements to work in the fields, such as a basket, a hoe or a pick, as a reference to the task to be carried out which was awaiting them in the Afterlife, as the symbolic representation of their master. The iconography, texts, materials, colours and their placing in the tomb could suggest other symbolic meanings.

Sometimes they were placed in wooden boxes, which could be either simple ones or with sophisticated decoration. In the New Kingdom they came to be placed in miniature sarcophagi.

While at first they were considered to be replicas of the deceased, in the New Kingdom and later, the ushabtis came to be seen as servants or a manner of slave, and for this reason they were produced en masse. There were both women and men, including specialists in different activities. Sometimes they were under the supervision of overseers, and these were distinguished by the use of a kilt. This is the case for the pharaoh Tutankhamun: he had three hundred and sixty five ushabtis at his command, one for each day of the year; thirty six overseers, one for each team of ten workers; and twelve master overseers, one for each month of the year. This came to a total of four hundred and thirteen servants in the Otherworld. The fear of having to carry out these tasks demanded of the dead by Osiris meant that in some burials there were even ushabtis who were there to act as substitutes or stand-ins, if necessary, for the main ones.

It is logical to think that no pharaoh would have wanted to carry out this type of task personally, and so at the necessary moment the utterance written on the body of the ushabti was read out so that this object acquired life to answer to the call, substituting for the pharaoh in the work.

Kanawati, N., "The tomb and its significance in Ancient Egypt" (Giza, 1987)

Kitchen, K., "The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt" (Warminster, 1973)

Nicholson, P., "Egyptian Faience and Glass" (Buckinghamshire, 1993)

Petrie, W.M.F., "Shabtis" (London, 1935)

Schneider, H. D., "Shabtis" vols. 1-3 (Leiden, 1977)

Ranke, H., "Die Agyptischen Personannamen" vols. 1-2 (Holstein, 1935)

Notes:

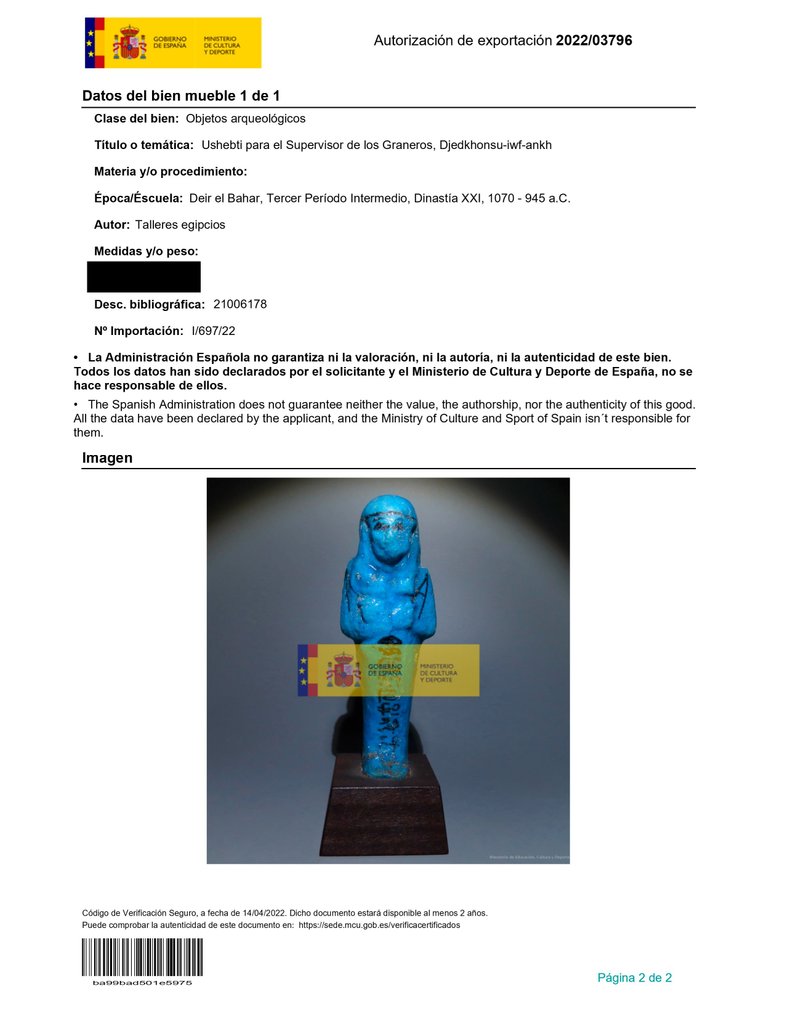

- The piece includes authenticity certificate.

- The piece includes Spanish Export License (Passport for European Union).

- The seller guarantees that he acquired this piece according to all national and international laws related to the ownership of cultural property. Provenance statement seen by Catawiki.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE FROM SPAIN ASKS ALL SELLERS FOR INVOICES OR OTHER DOCUMENTATION ABLE TO PROVE THE LEGALITY OF EACH ITEM BEFORE PROVIDING AN IMPORT OR EXPORT LICENSE.

#ExclusiveCabinetofCuriosities

Povestea Vânzătorului

Ushabti or Shabti Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh, the 'Overseer of Granaries',

- important shabti -

- nice blue color -

-museum quality-

The front has a vertical column of text: "The Osiris, overseer of granaries, Djedkhonsu-iwf-ankh, justified".

Ancient Egypt, Third Intermediate Period, 1070 - 650 BC

MATERIAL: Faience

DIMENSIONS: Height 10,5 cm without stand.

PROVENANCE: Private collection, France, 1970 - 1980. Excavated by Herbert Winlock at Deir el-Bahri.

CONDITION: Intact.

Museum quality ushabti figure, named Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh, the 'Overseer of Granaries', Egyptian faience, Deir el-Bahri, Egypt, Dynasty 21, Third Intermediate Period (1080-945 BC)

On the cover of the more than 1.100 pages book about shabtis from Luis Manuel de Araujo, Estatuetas funerárias Egípcias da XXI dinastia, a worker shabti from this series is printed on the cover, see photo. Several shabtis of this series were given to foreign musea by the Egyptian authorities and sold to private collectors at the end of the 19th century.

The iconography and purpose of the ushabtis seem to have been standardized from the late New Kingdom.

The statuette is in the form of a mummy, wrapped in a shroud and standing upright with both feet together. The hands are crossed on the chest and hold a pair of A-shaped hoes, tools necessary for agricultural work, and seed sack, painted in black. The ushabti wears a tripartite wig with locks of hair indicated by incised lines. The facial features are carefully modeled and suggest the individual portrait. The narrow tressed beard is attached under the chin.

The front has a vertical column of text: "The Osiris, overseer of granaries, Djedkhonsu-iwf-ankh, justified".

It was produced for a deceased man named "Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh" (whose tomb was excavated by Herbert Winlock at Deir el-Bahri). This name appears on other similar shabtis in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (E.9.1946 and E.10.1946), Kazan (15701), Lisbon (MNA E 99), Manchester, Moscow, New York (MMA 10.130.1063 a-d and 26.32.3), Toulouse and Winterthur (6780 (429)).

Ushabti were made from one original bi-valve mold. Once the two pieces were joined and the rough edges removed, and while the material was still moist, the details of the image were retouched and the columns were marked on which the hieroglyphs would be incised. This meant that each ushabti was unique, even though they had come from the same mold.

The material used for the creation of this ushabti is faience, composed of fine sand cemented with sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate extracted from natron. Fired at 950 degrees C, the mixture gives an enamel-like finish with the carbonates forming a vitreous surface. It was a simple procedure and therefore not costly. The green and blue tones were achieved by the addition of a few grams of copper oxide extracted from malachite or azurite. The red tones were achieved with iron oxide, the intense blues with cobalt, the black by mixing iron oxide and magnesium oxide with water. All that was needed was to paint the chosen details in the selected colour with a brush before the firing.

The Egyptian Afterlife was understood as a mirror of the real world, where both good and evil had their place. Those who were unfair or evil were punished for eternity, while the just enjoyed a comfortable existence travelling with the solar god. Even then, the deceased who were so blessed were still obliged to fulfil human responsibilities and needs, in the same way they had to in life. Their need to have food and drink in the Afterlife was a constant worry for them. If they were obliged to work in the Fields of Aaru, in the Realm of the Dead, and as members of a society which was a hierarchy governed by the gods, everyone – men and women, lords and servants, kings and queens – had to be willing to cultivate, sow and harvest the crops.

In the world of the living these basic tasks of production were carried out by the lower classes in society. To avoid this fate, Egyptians looked for a magic solution: they created one or more figures of themselves to be able to hand over to the emissaries of the reigning god, Osiris, when these called on the deceased to fulfil his obligations. These statuettes, placed amongst the grave goods in the tomb, were images which represented both the master and the servant.

They are known by the name of ushabtis, the term coming from sabty or shabty, derived from Sawab, the meaning of which corresponds to the Greek word “persea”, a sacred tree from whose wood the ancient Egyptians began to produce these funerary effigies. It was towards the Third Intermediate Period, in Dynasty XXI, around 1080 BC when they began to use the term wsbty, that is, “ushebty”. From then on the name “ushabti” derived from the verb wsb meaning “to answer” was used to name “he who answers”.

The use of ushabtis was incorporated into the burials in Ancient Egypt from the First Intermediate Period on. Their use grew during the Middle Kingdom, the time when the Egyptians began to write a spell in the Coffin Texts, number 472, so that the ushabtis would answer to the call: “The justified N. says ‘Oh ushabti, allotted to N, if N is summoned to do any work, or if a disagreeable task was asked of N as for any man for his duty, you are to say ‘I am here’. If N is called to watch over those who work there, ploughing the new fields to break the earth, or to ferry sand in a boat from east to west, you will say ‘I am here’. The justified N.”

This spell or utterance went on to be inscribed on ushabtis, and so in most cases, it appears there engraved. From the New Kingdom on, a great number of innovations were introduced. Examples with texts started to proliferate. Some of these were somewhat longer texts from Chapter VI in the Book of the Dead. Even so, in many cases the text simply indicates the name of the deceased, or a basic utterance, with the name of a family member or the posts that he held.

Ushabtis at first were made above all from wax, later from wood, and then towards the end of the Middle Kingdom they appeared in stone. From the New Kingdom on, the material par excellence was faience. We know they were produced in multiples thanks to moulds which have been preserved, and where in some cases, the engraved texts were unfinished, as the name of the owner was missing. The most popular form was that of the mummy until the introduction, towards the end of Dynasty XVIII, of figures decorated with everyday clothing. Many carried implements to work in the fields, such as a basket, a hoe or a pick, as a reference to the task to be carried out which was awaiting them in the Afterlife, as the symbolic representation of their master. The iconography, texts, materials, colours and their placing in the tomb could suggest other symbolic meanings.

Sometimes they were placed in wooden boxes, which could be either simple ones or with sophisticated decoration. In the New Kingdom they came to be placed in miniature sarcophagi.

While at first they were considered to be replicas of the deceased, in the New Kingdom and later, the ushabtis came to be seen as servants or a manner of slave, and for this reason they were produced en masse. There were both women and men, including specialists in different activities. Sometimes they were under the supervision of overseers, and these were distinguished by the use of a kilt. This is the case for the pharaoh Tutankhamun: he had three hundred and sixty five ushabtis at his command, one for each day of the year; thirty six overseers, one for each team of ten workers; and twelve master overseers, one for each month of the year. This came to a total of four hundred and thirteen servants in the Otherworld. The fear of having to carry out these tasks demanded of the dead by Osiris meant that in some burials there were even ushabtis who were there to act as substitutes or stand-ins, if necessary, for the main ones.

It is logical to think that no pharaoh would have wanted to carry out this type of task personally, and so at the necessary moment the utterance written on the body of the ushabti was read out so that this object acquired life to answer to the call, substituting for the pharaoh in the work.

Kanawati, N., "The tomb and its significance in Ancient Egypt" (Giza, 1987)

Kitchen, K., "The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt" (Warminster, 1973)

Nicholson, P., "Egyptian Faience and Glass" (Buckinghamshire, 1993)

Petrie, W.M.F., "Shabtis" (London, 1935)

Schneider, H. D., "Shabtis" vols. 1-3 (Leiden, 1977)

Ranke, H., "Die Agyptischen Personannamen" vols. 1-2 (Holstein, 1935)

Notes:

- The piece includes authenticity certificate.

- The piece includes Spanish Export License (Passport for European Union).

- The seller guarantees that he acquired this piece according to all national and international laws related to the ownership of cultural property. Provenance statement seen by Catawiki.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE FROM SPAIN ASKS ALL SELLERS FOR INVOICES OR OTHER DOCUMENTATION ABLE TO PROVE THE LEGALITY OF EACH ITEM BEFORE PROVIDING AN IMPORT OR EXPORT LICENSE.

#ExclusiveCabinetofCuriosities

Povestea Vânzătorului

- 750

- 7

- 0

Wunderbares Stück. Alles wie beschrieben. Hervorragender Kontakt.

Vizualizați traducereaExtremely rapid courrier service from Barcelona to Flanders, picture was nicely and carefully packaged. Muchas gracias!

Vizualizați traducereaVery fine specimen! Thanks.

Vizualizați traducereagoede foto's, goede omschrijving, goed verpakt en snel verzonden.

Vizualizați traducereamolto bello tutto ok

Vizualizați traducereaPezzo come da descrizione, davvero notevole. Venditore molto consigliato in quanto gentile e disponibile. spedizione molto veloce. Ottimo!

Vizualizați traducereaVenditore davvero ottimo e gentile. Merce come da descrizione, spedizione veloce. Ottimo l'avere certificato di autenticità.

Vizualizați traducereaUn 100 como empresa un 100 como envío . Empresa muy especial con mucha exquisitez en todos los productos y en personal . Muchas gracias

Vizualizați traducereaAll well! Thanks.

Vizualizați traducereaVery nice and fine cut little jewel! Well packed too! Thanks!

Vizualizați traducereanice piece and very fast shipping!

Vizualizați traducereaEs una maravilla de moneda, donde se le nota los pasos de los años y me encanta. Servido muy rápido y bien empaquetado. Con su certificación. Qué más se puede pedir?

Vizualizați traducereaSnelle en correcte levering, alleen was de verpakking voor het schilderij niet stevig genoeg.

Vizualizați traducereaHerzlichen Dank!

Vizualizați traducereaAll OK and with very fast shipping.

Vizualizați traducereaPrachtig schilderij. Zo blij mee. Zeer nette verkoper en zeer snelle levering.

Vizualizați traducereaperfect ! very fast and high quality delivery !

Vizualizați traducereaAll well! Thanks.

Vizualizați traducereaVendeur très professionnel, top +++×

Vizualizați traducereaPhotos trop contrastées pour bien percevoir les défauts, mais ces défauts étaient visibles pour autant. Le "Bon état" est trompeur. Sinon, envoi rapide et correctement emballé. Frais de port exagérés.

Vizualizați traducereaGreat communication, delivery and product. Came with a well made certificate of authenticity and good packaging. Overall very happy with the purchase! Delivery is a bit expensive, but I recommend it

Vizualizați traducereaMagnifique témoin du passé, envoyé avec tous les justificatifs, impeccable. Encore une fois très satisfait, un grand merci

Vizualizați traducereaThank you for the Special offer and the fast shipping of this excellent piece of art!

Vizualizați traducerea