羅馬 大理石 帶有彩色遺跡的浮雕碎片 - 21×17×.. cm

編號 82682891

編號 82682891

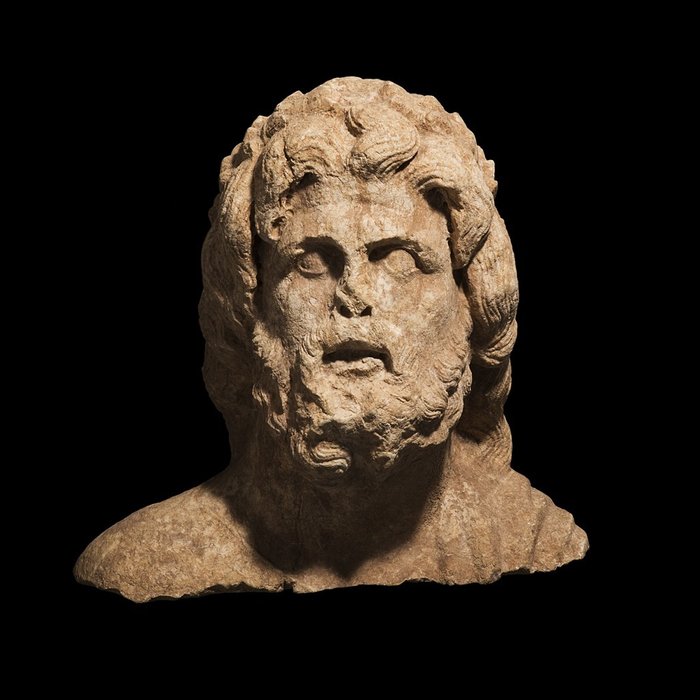

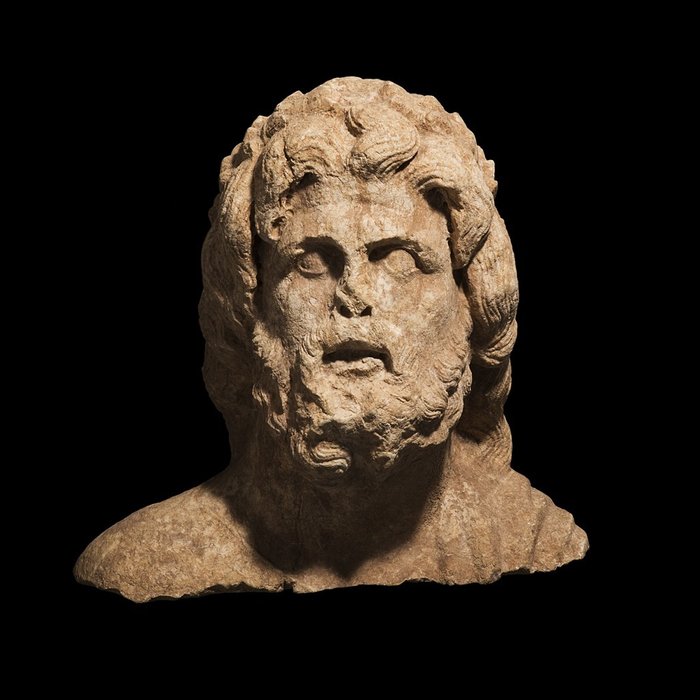

Monumental head of the god Sabazios

CULTURE: Greek

PERIOD: Hellenistic Period, 2nd century BC

MATERIAL: Marble

DIMENSIONS: Height 43.5 cm

PROVENANCE: From a private German collection. Acquired from the Galerie Puhze, in Freiburg, in 1985.

PUBLICATIONS: - Catalogue "Kunst der Antike 6", Freiburg im Breisgau, 1985, N. 28.

- Optimus Princeps. J. Bagot Arqueología. Barcelona. 2017. Fig 29.

- Aisthetike. J. Bagot Arqueología. Barcelona. 2018. Fig 22.

CONDITION: In a good state of preservation. In its original state without any restoration.

DESCRIPTION:

A monumental bust extoling the Phrygian god, Sabazios. It is sculpted from a single block of marble and has an earthy-brown patina. The head is slightly inclined to the right. His mighty mane of hair arranged in waving tresses and his thick curly beard stand out. A crown of laurel leaves rests on the head. The bust is made up of the head and neck with only a small part of the shoulders remaining. The piece was previously part of a monumental sculpture in one of the temples dedicated to this god.

The garments that would be covering the body can be seen over the shoulders: a light tunic visible over the right shoulder, and a bulkier cloak covering the left shoulder. These garments might be respectively, a chiton and a himation.

The expression on the face is poetic, almost dramatic, expressing a strong sense of melancholy. The gaze is fixed; the mouth a little open and movement expressed through the hair and the beard. These features point to the chronology of the sculpture, which would be between the middle of the 3rd century and the middle of the 2nd century BC. This was a period when, in the Hellenistic world, a baroque-type current, the “School of Pergamon”, was dominant. It was marked by ornamental motifs, complex pyramidal compositions, with figures in anguished, dramatic poses and with exaggerated musculature.

The preferred theme of the Hellenistic artists was the struggle of the Pergamon monarchs against the Galatians when the latter invaded Asia Minor. They created figures depicting these battles and which celebrate their victory, such as the Ludovisi Gaul in Rome. These are works overflowing with pathos and drama, with many characteristically anecdotic details.

In contrast, the most important relief in the Pergamon Altar of Zeus is the Gigantomachy frieze, which represents the clearest example of a sentiment of ferocity with a twisting and turning rhythm. It is a monumental composition, both for the scale of the exterior frieze as well as for the great number of characters – over one hundred – who are depicted. The frieze in the lower part of the structure is original, in that the sense of grandeur is heightened by the proximity of the viewer. It is here that the sensation of movement and the intensity of the action reach their highest expression, thanks to the diversity of the poses and the exaggeration of the gestures. The expression of anguish and pain of the giants who are defeated by the gods, as well as the so-named “horror vacui”, reinforce this baroque-like idea. The tension sculpted in the musculature of the male figures and the movement of the female figures is important. As to their clothing, they bring to mind the work of Phidias, although in this case, the clothing is not subordinate to the body it covers.

Clearly this bust does not have a gaze as powerful as those on the Altar, but it is a clear example of the dramatism and monumentality of this artistic current.

Sabazios is a god of mystery, of orgiastic and telluric character. In the Greek and Roman inscriptions his name appears with prominent adjectives like saintly, invincible and great, along with his designation as a divinity.

It seems that Thrace is the birthplace of the mystery of this god. From there, in the 5th century BC, he came to Greece through Phrygia, along the route normally followed by the Thraco-Phrygian caravans. In the 4th century BC, the epoch of splendour of individualistic aspirations of piety, his cult was consolidated. During the Hellenistic period it reached its greatest moment of expansion, arriving in Rome through the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia (Italy).

The myth of Sabazios has its roots in the telluric substratum. The defining features of this god, along with his origin and the trajectory of the diffusion of his cult, explain the diverse implications of the syncretism of which he was the object.

Frequently in the Greek world he was assimilated into Dionysus, and was considered as a more ancient Dionysus, son of Zeus and Persephone. The numerous features in common between Sabazios and Dionysus stem from their nature as young gods of vegetation. The idea of domesticating oxen and submitting them to the yoke is attributed to him. This explains the images where he is represented with horns on his forehead. According to certain myths, after Dionysus arrived in Phrygia, the Great Mother of the Gods (known in Asia Minor as Cybele and among the Greeks as Meter-Gaea, Rea or Demeter) initiated him into the mysteries and he took on the name of Sabazios. This is the reason why he was worshipped in Athens in the very temple of the goddess Demeter (Rea). Part of his cult included the annual death of the god in the cornfields, where the participants in this ritual would weep for him.

His celestial condition is in a certain manner a reflection of the Thracian celestial god. These are incompatible with Dionysus but, on the other hand, explain his identification with Zeus and Jupiter. This is yet another case of the absorption of cults and inferior divinities by a god with a much stronger cult. Tradition assimilates him as a descendent of Zeus. The latter had coupled with Persephone taking on the form of a snake and had engendered Sabazios. The snake was, of course, a sacred animal of the god and had an important role in his mysteries. Myth has it, for example, that the god had also coupled in the form of a snake, with one of his priestesses in Asia Minor, who then bore him children.

Sabazios does not strictly speaking form part of the Greek pantheon. He is imported, and does not possess his own personal cycle of myths, or at least exoteric myth. Perhaps, in the mysteries celebrated in his honour, his legend was richer. His mysteries had a certain fame, as he was a god chosen by his devotees, not a common deity. A priest of Sabazios had the following written on his tomb: “Eat, drink and be merry before coming to join me. While you live, enjoy yourself, and only bring this to me. Here lies Vicentius, priest of Sabazios, who celebrated the holy and divine rites.”

Little is known about the rites and ceremonies that were developed around his cult. It would seem that his followers had eschatological aspirations and that in their ceremonies of initiation there were abundant elements related to the agricultural cycle and the fruitfulness of the fields. In this way, the initiate had a mixture of dirt and bran scattered over him while these words were pronounced: “I ran from evil and found what was best” (Demosthenes, On the Crown 259). Both the ritual and the formula allude to resurrection after death, and all of it has a strange similarity with the Christian rite of baptism. Other initiation ceremonies had to do with snakes. In this case, there was an evident telluric meaning, which we see repeated in many other religions of mystery originating in the East. Above all, there was one with undeniable sexual content, during which a metal serpent was placed underneath the garments of the initiate, and which, in the opinion of the experts, was meant to be a form of sexual union with the god. That is why Sabazios was frequently called “God between the folds of the tunic”, or “God through the abdomen”. When one considers the conditions in which these initiation ceremonies into the mystery cults were held, it would seem that this one in particular must have been, at the very least, terrifying for the initiates, who didn’t know for sure what they were going to find in a space, poorly illuminated by burning torches.

In Asia Minor, the spread of the cult of Sabazios seems to have been influenced by the ruling monotheism in the last years before the coming of Christ, above all due to the number and importance of the Jewish communities established there. It can be imagined that this monotheistic climate made possible the implantation of the Christian religion a few years later.

In Spain the presence of the cult of Sabazios has been documented with considerable evidence, specifically along the Mediterranean coast. As can be imagined, this was due to the fact that the region was open to the sea. Thanks to trading, it was more open to eastern influence and the adoption of foreign divinities, which in many cases ended up conflated with other local gods. One of the pieces conserved in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología in Cartagena, is a "Hand of Sabazio". This type of piece was relatively common, and different museums have similar examples, which are almost the only images that make reference to this god, with the exception of a very few busts like this one.

The hand here mentioned is making a gesture of blessing called “Benedicito Latina” and it is associated with various symbols. It corresponds to the sort of Mano Pantea related to the cult of Sabazio, an authentic liturgical object which may have been affixed to a sceptre in processions, or destined to be placed in sanctuaries or for use in domestic cult. This votive hand in bronze conserved in Cartagena comes from Phrygia, and contains a figurine with a Phrygian cap and breeches, with the feet placed on the head of a ram, raising the thumb, the index finger and the middle finger in the gesture of the “Benedicto Latina”: the thumb of Venus to obtain prosperity, the index finger of Jupiter which guides one to a destiny and the middle finger of Saturn for rain. The figurine imitates the gesture of the hand which is holding it, and Jupiter’s eagle sits on the index finger. This was not so much a gesture of blessing as a propitiatory gesture used before the beginning of a recital or discourse: Greek and Latin orators never omitted this.

PARALLELS:

- Bust of the god Sabazios, Roman Empire, 2nd Century AD, bronze. Musei Vaticani, Rome, Italy.

- Relief of Zeus, Roman Empire, 1st-2nd Century AD, marble. Burdu Museum Turkey.

- Sculpture of the god Zeus-Sabazios, Roman Empire, 170 – 230 AD, marble. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

- Bust of the god Dionysus-Sabazios, Roman Empire, bronze. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Naples, Italy.

Notes:

The seller guarantees that he acquired this piece according to all national and international laws related to the ownership of cultural property. Provenance statement seen by Catawiki.

The seller will take care that any necessary permits, like an export license will be arranged, he will inform the buyer about the status of it if this takes more than a few days.

The piece includes authenticity certificate.

The piece includes Spanish Export License (Passport for European Union) - If the piece is destined outside the European Union a substitution of the export permit should be requested.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE FROM SPAIN ASKS ALL SELLERS FOR INVOICES OR OTHER DOCUMENTATION ABLE TO PROVE THE LEGALITY OF EACH ITEM BEFORE PROVIDING AN IMPORT OR EXPORT LICENSE.

#ExclusiveJurassicAntiquity