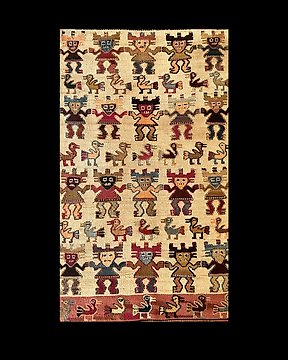

Chançay Arazzo in lana camelide. Licenza di esportazione spagnola. 76 x 42 cm. Danza cerimoniale di esseri multirazziali che si tengono per mano. - 76 cm

N. 84111063

N. 84111063

Decorative discs with a carved depictions of the Moche deity Ai Apaec, most feared and adored of all punitive gods, it was also referred to as the “headsman”and was worshipped as the creator god, protector of the Moche

Enriched copper alloy circular discs of stylised jaguar face having heavy gilt surfaces. Repoussé method of decorating metals in which parts of the design are raised in relief from the back or the inside of the article by means of hammers and punches. Moche and later Inca artisans created feline imagery over and over again, with the focus often being the animals' faces and in particular their mouths full of sharp teeth. Peruvian cultures, associated felines with military, religious, and political leaders; the animals' method of attacking the head of its prey was also a symbol for decapitation in a culture that revered taking trophy heads.

Frontal decorations of copper alloys : One of the most frequent themes in indigenous art is the race of human beings or anthropomorphic beings with animal features. In this race, the runners participate in their best clothes, and they wear elaborate head and body decorations. One of the most characteristic is the circular frontal ornament. .

Brass: a copper-zinc alloy that was used by some Andean cultures, such as the Moche and the Chimu has a yellowish color and a lower melting point than copper alone. The proportion of zinc to copper in brass can range from 1% to 40%.

Alloy Metallurgy

The availability of certain metals also played a crucial role in determining the composition of these alloys. Andean societies had access to various mineral resources, and they utilised what was readily available to them. This influenced the choice of alloying elements. If a particular region had abundant zinc or nickel resources, it might lead to a higher usage of these metals in the local copper alloys.

The knowledge and technological expertise of the metallurgists of these civilisations also played a role in alloy composition. They experimented with different ratios of metals to achieve the desired properties and characteristics for specific applications.

It's important to note that the exact composition of these alloys can vary widely between different artefacts and time periods. There isn't a single fixed composition for Ancient Peruvian copper alloys because each piece was tailored to its specific purpose and the available resources at the time of creation. Analysing the composition of these alloys through modern techniques like X-ray fluorescence or mass spectrometry has provided valuable insights into the metallurgical sophistication of these ancient cultures.

The continuity of traditional metallurgy skills from the Pre-Columbian and Inca cultures during the colonial period in Peru is indeed a complex and multifaceted historical phenomenon. This topic sheds light on the resilience of indigenous knowledge and the ways in which it adapted and transformed in the face of European colonisation. To explore this topic in depth, we can examine it from several angles.

The use of nickel and zinc in copper alloys in Peru can be linked to the influence of European metallurgy, especially during the colonial period. Some Andean cultures, such as the Lambayeque, the Chancay, and the Inca, used these metals for making various objects such as ceremonial knives, funerary masks, vessels, and ornaments.

Regarded today for their craftsmanship and historical significance, their metalworking techniques involved the use of copper, gold, silver, and metal alloys. Ancient metalworkers of Peru experimented with different alloys of copper, tin, gold, silver, and other metals to create various colours, strengths, and effects. Zinc and nickel were among the metals that were sometimes added to copper to produce bronze alloys. For example, one source states that a bronze knife from Peru had a composition of 82% copper, 13% zinc, 3% nickel, and 2% iron.

Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallurgy_in_pre-Columbian_America

Another source mentions that some Peruvian bronze objects had up to 5% zinc and 1% nickel:

Ancient metalworking in South America: a 3000-year-old copper mask from the Argentinian Andes.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/ancient-metalworking-in-south-america-a-3000yearold-copper-mask-from-the-argentinian-andes/80E3CFE81BC10CFFA5602230A16B40DF

Pre-Columbian Metallurgy in the Andes:

Before the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century, the Andean region, including what is now modern-day Peru, was home to advanced metallurgical practices. The Inca Empire, in particular, was known for its skilled metalworkers who crafted intricate jewellery, ceremonial objects, and tools primarily from gold and silver. This metallurgical expertise was deeply ingrained in the Inca society and had religious and cultural significance.

Impact of Spanish Conquest:

With the arrival of the Spanish, many aspects of indigenous cultures, including metallurgy, were disrupted. The Spanish sought to extract precious metals for export, leading to the exploitation of indigenous labour and the melting down of precious objects. This disruption threatened the continuity of indigenous metallurgical skills.

Syncretism and Adaptation:

Despite the disruptions, indigenous artisans adapted to the new colonial context. They began to incorporate European techniques and materials, such as copper, into their traditional practices. This led to a fusion of indigenous and European styles, resulting in unique forms of colonial art and jewellery that incorporated elements of both worlds.

Continuation of Traditional Knowledge:

In some cases, indigenous metallurgists managed to preserve their traditional knowledge secretly. They continued to create pieces in the pre-Columbian style, hidden from Spanish authorities. This underground resistance allowed the preservation of traditional techniques and forms.

Religious and Cultural Significance:

Metallurgy had profound religious and cultural significance in the Andean societies. Many of the objects created during the colonial period continued to be used in religious ceremonies and were essential for maintaining cultural identity.

Legacy and Revival:

The resilience of traditional metallurgy skills is reflected in the continued existence of skilled indigenous artisans in Peru. In the modern era, there has been a resurgence of interest in traditional techniques and a revival of pre-Columbian styles in contemporary art and jewellery.

References:

Rowe, John H. "Inca culture at the time of the Spanish conquest." Handbook of South American Indians, Vol. 2: The Andean Civilizations (1946).

Brundage, Burr Cartwright. "Empire of the Inca." University of Oklahoma Press, 1963.

Bray, Tamara L., et al. "Materializing colonial encounters: Peruvian silverwork, 1600-1800." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 10.1 (2000): 55-77.

Peters, Damie. "Crafting Inca jewelry in the Spanish colonial Andes: Metalwork, gender, and material culture." In Gender in Pre-Hispanic America, pp. 73-95. Springer, 2017.

Moore, Jerry D. "Metals and Metallurgy in the Pre-Columbian Americas." Handbook of South American Archaeology (2008): 51-67.

This complex history of continuity and adaptation in metallurgy is a testament to the resilience and cultural richness of indigenous traditions in the face of colonial challenges.

Salvador Rovira "Inca metallurgy: study from the collections of the Museum of America in Madrid"

https://journals.openedition.org/bifea/8155

Artwork with well-documented legal provenance and Spanish Historical Patrimony Export Certificate. The Ministry of Culture from Spain asks all sellers for invoices or other documentation able to prove the legality of each item before providing an import or export license.

Family Heirloom Private Collection Ex. Dr Rivadeneyra collection, Berlin late 1960s to early 1970s. To present owner by descent.

Collected through the years by my father Dr. Jose Rivadeneyra Leon and by my grandfather

Engr. Julio Rivadeneyra who lived in northern Peru central coast near Chiclayo.

Privately purchased and/or gifted by family members who loved collecting like his cousin,

Carlos Williams Leon who was a Peruvian renowned architect and archeologist. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Williams_Le%C3%B3n/

Most of the collection was taken to Berlin in 1969 where my father was doing medical research.

Any other costs or charges such as customs or import duties, customs clearance and handling may also apply during the shipment of your lot and will be charged to you by the involved party at a later stage if applicable.

Any necessary permits are/will be arranged. The seller will inform the buyer immediately about any delays in obtaining such permits.

If the piece goes outside the European Union a new export license will be requested by us, this process can take between 1 and 2 months. Items sent outside the European Union are subject to export taxes and will be added to the invoice, at the buyer's expense. These export fees are fixed on the final auction price and the tax rate is not applied directly on the total value of the item to be exported, but rather the different percentages by sections are applied to it:

- Up to 6,000 euros: 5%. Shipped with Insurance.

Item legal to buy/sell under U.S. Statute covering cultural patrimony Code 2600, CHAPTER 14

This object is subject to the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Protection Act. For shipment to a non-EU member state, export regulations will vary.

Come fare acquisti su Catawiki

1. Scopri oggetti speciali

2. Fai l’offerta più alta

3. Paga in tutta sicurezza