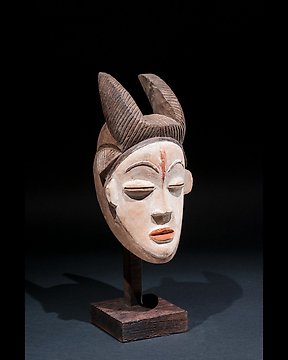

KWELE

Nr 82726379

Nóż do rzucania/waluta - Kapsiki - Kamerun

Nr 82726379

Nóż do rzucania/waluta - Kapsiki - Kamerun

This crested bird-shaped throwing knife/currency hails from the remote northern region of Cameroon, nestled within the Mandara Mountains and inhabited by the Kapsiki and Fali people. It showcases a sturdy rusty patina, adorned with intricate small dot patterns. Remarkably, the leather covering on the handle remains intact. Its origins trace back to the early 20th century or potentially even earlier. The bronze-finished steel base is of high quality.

Some words about African iron currencies.

Ancient texts mention the use of iron currency in East Africa as early as the 1st millennium AD in Ethiopia. Copper coins circulated in West Africa during the 2nd millennium AD. In the Akan world (Ghana), iron coins were in use before the introduction of gold dust, as specified by O. Dapper in 1686. These were small iron rods primarily used for minor transactions and held less value than copper.

With the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century, European iron entered West Africa in the form of bars, becoming so significant that by the 17th century, on the Senegambian coast, the iron bar or "barriferri" became the standard unit against which goods were evaluated. English explorer Mungo Park observed in 1796 regarding the inhabitants of Gambia: "It was mainly iron that attracted their attention. Its utility in making weapons and tools for cultivation makes it superior to all other metals." An enslaved person was worth 150 bars at that time.

In the 19th century, other forms of iron rods circulated in West Africa under various names like "guinze" or "sompe." They consisted of an elongated body with the lower part flattened by hammering and an upper part consisting of a strip of iron added hot and hammered.

In Chad, some currencies depicted a crescent shape, while among the Kota (Gabon, Congo), they were simply varying weights of iron masses.

In Central Africa, the forms varied, ranging from hoes, single or double bells, arrowheads, and even hairpins. J. Rivallain, who provided much of the information above, further notes: "Hair served as storage space, a wallet, for people moving about scantily dressed. The pins, stuck in the hair, had little chance of getting lost." Among the Zande, only women used them as currency. For major transactions like marriage or land purchase, weapons were used for payments, with some undergoing modifications in shape or size. From combat weapons, they transitioned to prestige weapons and then to currency weapons. Freed from functional necessities (maneuverability, resistance), these often became artworks in the eyes of Westerners.

Bibliographic source: Meyer, Laure - Les arts des métaux en Afrique noire – Sepia, 1998

Przedmioty, które mogą Ci się spodobać

- 16+

Ten przedmiot został zaprezentowany w

Jak kupować w serwisie Catawiki

1. Odkryj coś wyjątkowego

2. Złóż najwyższą ofertę

3. Dokonaj bezpiecznej płatności