Oud-Romeins bronzen Bacchische Panter - 3.3 cm

Nr. 82773961

Nr. 82773961

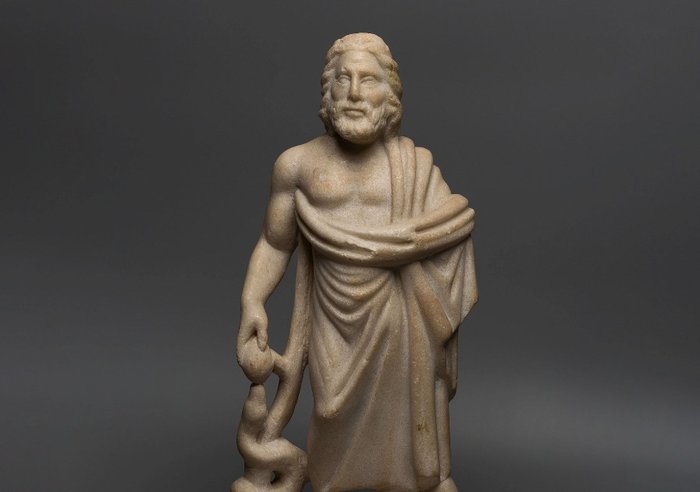

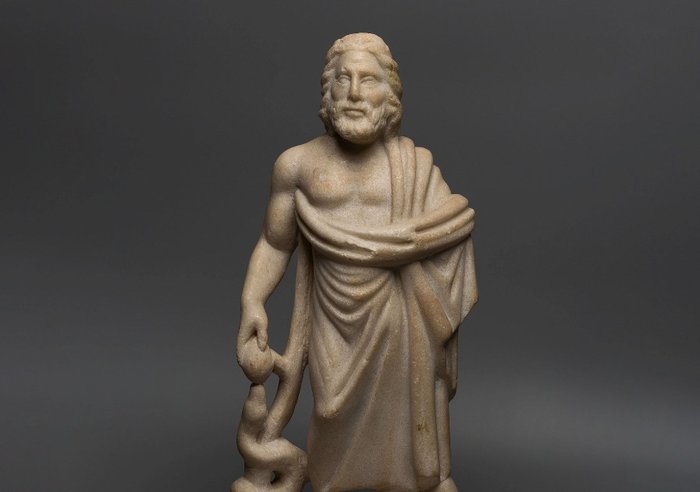

GOD AESCULAPIUS

Marble, with remains of original iron pin on the back side and some bronze deposits on the base.

Height 43 cm

Provenance: Auction House Paris, France.

Good condition, intact and unrestored.

Description:

Roman marble statuette representing Asclepius/Aesculapius, Greek and Roman god of medicine. It is carved in a round shape, although the back part shows a rougher, sketched finish, since it would have been hidden from the viewer's eyes. In fact, the back preserves remains of an iron fixing pin, which has stained the stone reddish; This piece would have allowed the sculpture to be secured to a niche or wall, making it impossible to see its back.

The work shows a somewhat disproportionate anatomical treatment, with a large head and a very long torso in relation to the legs. However, the sculptor has been able to give the image a slow and elegant movement, as evidenced by the carving of the right arm, which extends relaxed in a graceful and soft movement. The god Asclepius is represented as is usual in Greco-Latin art, as a mature, bearded man with long hair. The muscular torso reflects the Greek ideal of virility, being that of a man in the prime of his life. The face turns slightly to the left side, and is perfectly framed, symmetrically, by the thick beard and hair, which fall in curls on both sides of the face. The facial expression reveals the serenity of a god, with a closed but relaxed mouth, thick lips, wide-open, almond-shaped eyes with differentiated upper eyelids, and a forehead furrowed by a single horizontal wrinkle, which reveals concentration, activity of the mind in contrast to relaxation of the body.

The posture follows a soft contrapposto, with the weight of the body supported on the left leg, which remains tense in contrast to the right, which is flexed by advancing the knee and slightly raising the foot, whose heel is separated from the ground. In contrast, the right arm is the one that is extended while the right arm is bent at the elbow, resting the hand on the hip. The god holds an egg in his right hand, towards which is approached the head of the snake that is coiled around his staff. The latter is especially long, extending until its upper end is lodged in the armpit; The rod thus functions as a prop that helps support the weight of the sculpture. The god appears dressed in a himation or mantle that, rolled over the torso, under the pectorals, passes over the arm at the elbow and crosses the back horizontally. Over the left shoulder, one end of the cloak falls vertically, forming a soft zigzag in its profile. The other end covers the body from the waist, forming well-defined folds, carved with great depth based on diagonal lines that reveal the anatomical shapes, including the right knee, which can be clearly seen under the fabric.

The statuette features rare iconography, called the Nea Paphos-Alexandria-Trier type after the cities hosting the first three identified examples: Nea Paphos in Cyprus, Alexandria in Egypt, and Trier in Germany. These are images of a smaller format than life, between 14 and 119 cm high, which present the god Asclepius standing, following the usual formula of himation and rod with the snake, but adding an egg in his right hand. All these works follow the same compositional structure, with the position of the body and cloak close to the type of Asclepius Amelung (archetype of the cult statue of the Asclepeion of Epidaurus), although some examples can be related to the type of Asclepius Eleusinus, very similar. although it shows more bare surface of the torso and a cloak with more folds. The most common is the scheme illustrated by the piece under study, which we find practically identical in other examples of the type (fig. 1): folds grouped horizontally across the width of the torso, vertical fall over the shoulder, triangular folds under the elbow and above the belly and one or several very marked folds that fall diagonally from the left hip to the right ankle.

This is a very small group of works – in 2014 only eighteen examples were known – that presents great compositional and iconographic uniformity, although it contains some variants. Most of the pieces have a particularly long rod, held in the armpit and functioning as a structural element (fig. 2). The god is always represented with a thick beard, but there are two variants for the hair: long and divided in the center and, less frequently, with two long curls hanging on both sides of the face (fig. 3), as is the case of the piece that concerns us. Finally, some statuettes of the Nea Paphos type show the god accompanied by his son Telesphorus (fig. 4), who represents recovery from the illness. Hygieia, daughter of Asclepius and goddess of hygiene, also appears in a single example. All these works come from domestic or religious contests.

The type of Asclepius Nea Paphos-Alexandria-Trier was identified by G. Grimm in 1989. According to him, it would have its origin in the small Greek city of Abonutico, on the coast of the Black Sea (present-day Inebolu, Turkey), during the second half from the 2nd century AD There, around the year 165 AD, the famous Alexander of Abonuticus, called the False Prophet, became famous, creating a new cult of Asclepius based on the belief that the god of medicine had once again incarnated in the serpent-god. oracular Glycon, born from a goose egg. The popularity of this new cult was such that, during the Marcomannic wars, the Romans took into account one of its oracles, proclaimed by Alexander, according to which a great victory would be achieved if two lions were sacrificed in the waters of the Danube. The Romans followed the advice, but the battle turned out to be an absolute disaster, with some 20,000 men killed; Alexander would later excuse himself by saying that the oracle had not specified which side would be the victor. Grimm directly relates the snake and egg symbols of the Nea Paphos type to Glycon, and theorizes that all statuettes representing this new iconography would therefore be copies of the cult image of Asclepius made for the temple of Glycon at Abonuticus.

In the mid-1990s F. Sirano studied the type again and provided new examples. In his analysis of the expanded corpus of images, he proposes that the archetype for this iconography would be the cult statue of the Asclepeion of Cos, one of the Greek islands of the Dodecanese. Specifically, the type would follow the model of the new cult image placed in the sanctuary in the 2nd century AD. After the reconstruction of the temple, C. Sirano also questions the connection of the Nea Paphos type with the cult of Glycon, based on the great difference between the serpent on the staff of Asclepius and the iconography of the oracular god, represented as an ophidian body curled up on itself, with human hair and ears (fig. 5).

In the most recent study to date, from 2014, V. Mazzuca once again expands the catalog of examples of the Nea Paphos type and reconsiders the matter. He adds seven more works to those identified by Grimm and Sirano, reaching a total of eighteen, which allows him to come up with new hypotheses. He concludes that the iconographic type of Asclepius holding an egg in his right hand is represented by statuettes from the full imperial period, mainly from the second half of the 2nd century AD, although some are dated between the 3rd and 4th centuries (fig. 6). They come from mainland Greece, Asia Minor, the Greek islands, Alexandria, the Danube provinces and Rome. Therefore, it does not appear in the Western Mediterranean, but only around Greece (except for the two examples from Rome) and, more specifically, Thrace. Mazzuca considers that the type does not reproduce the cult image of an important sanctuary, because if it were so there would be many more copies and more widely spread. Although it follows the type of Asclepius Amelung, the most widespread in the territory of the Empire, the appearance of the egg is rare; The scholar proposes that this very specific iconography could be related to a very specific cultural environment, that of the medical profession. He quotes Galen's words about the Hippocratic Oath, clearly addressed to doctors, in which he describes how Asclepius should be represented: a bearded man leaning on a wooden staff around which a snake is coiled, in his right hand a egg that symbolizes the Universe, alluding to the universal need for Asclepius' medicine. Mazzuca proposes that the Nea Paphos type could therefore be related to the doctors and the places where they carried out their activity, that is, the sanctuaries of Asclepius. They would probably be votive statuettes offered to the god by the doctors themselves.

Hero and god of medicine, Asclepius was venerated in Greece and, later, in Rome under the name Aesculapius. He received his first medical teachings from his father, Apollo, although he was later instructed in the art of medicine by the centaur Chiron, and received secret knowledge from a snake, a sacred animal in Greece and associated with wisdom, healing. and the resurrection. Other versions narrate that, when he was ordered to bring Glaucus back to life, he was confined in a secret prison. There a snake climbed up his staff and the god, lost in thought, unconsciously struck the staff against the ground and killed the animal. A second snake then appeared, carrying a herb in its mouth; He placed it on the head of his dead sister and she was resurrected. Seeing this, Asclepius used the same plant to get Glaucus to return from the dead.

During his life, Asclepius became the most renowned doctor in Greece, surpassing not only Chiron but also his own father, the divine Apollo, and was therefore awarded the power to bring the dead back to life. Hades, irritated at seeing how many of his subjects were taken from him, complained to his brother Zeus. Other sources explain instead that the king of Olympus was concerned that he would teach the art of resurrection to other human beings. In any case, Zeus ended Asclepius's life with one of his fearsome lightning bolts although, thanks to the intervention of Apollo, he finally granted him divinity and gave him a place on Olympus.

Notes:

- The piece includes authenticity certificate.

- The piece includes Spanish Export License (Passport for European Union) - If the piece is destined outside the European Union a substitution of the export permit should be requested, can take between 1-2 weeks maximum.

- The seller guarantees that he acquired this piece according to all national and international laws related to the ownership of cultural property. Provenance statement seen by Catawiki.

Zo koop je op Catawiki

1. Ontdek iets bijzonders

2. Plaats het hoogste bod

3. Veilig betalen