Bruno Munari - Libro illeggibile bianco nero giallo. - 1956-2011

Bidder 5982 Bidder 5982 | €69 | |

|---|---|---|

Bidder 0993 Bidder 0993 | €64 | |

Bidder 2354 Bidder 2354 | €59 | |

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123536 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

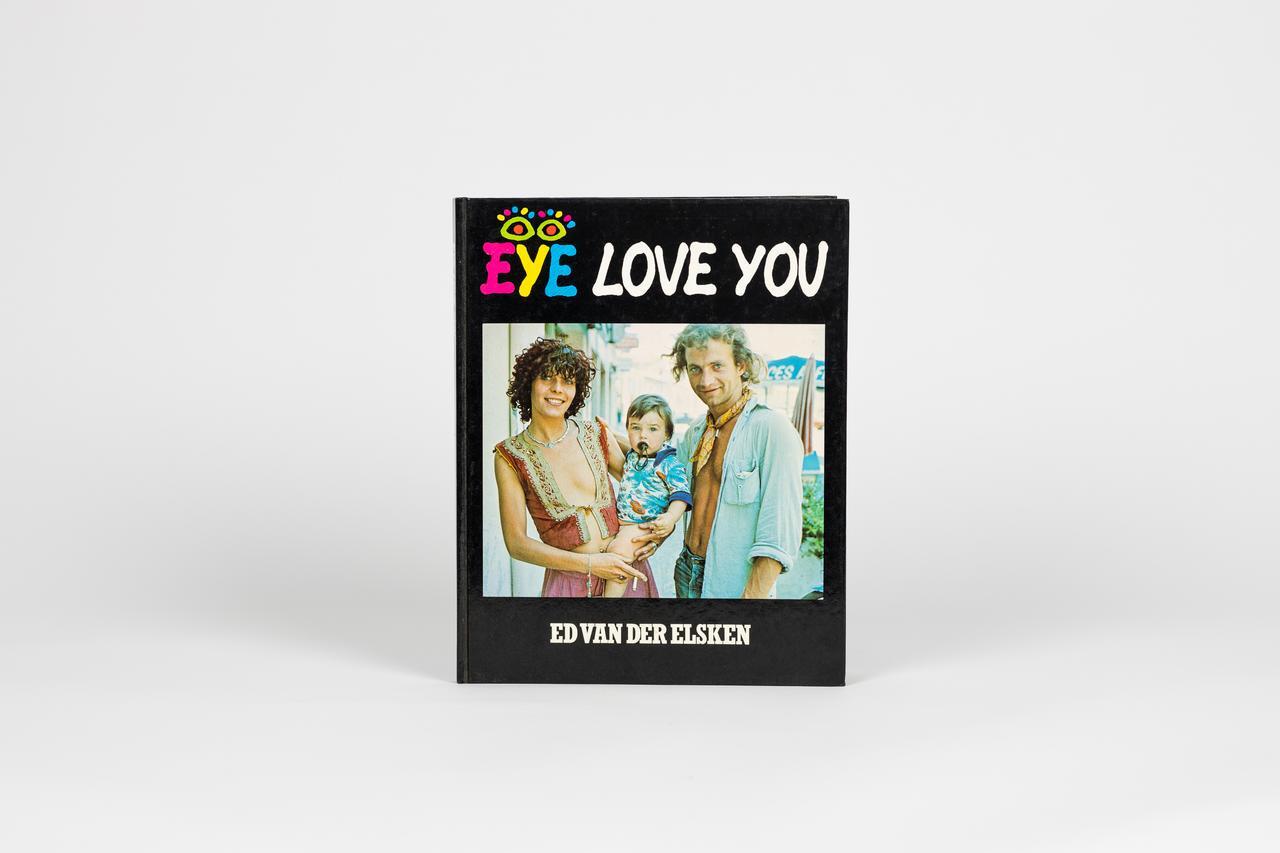

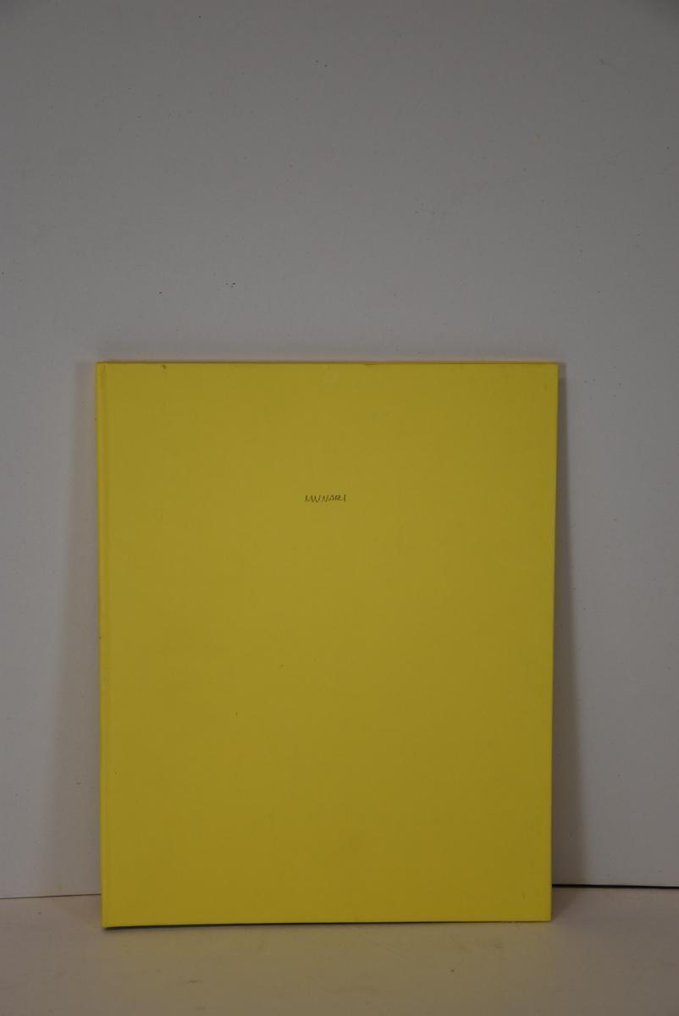

Bruno Munari's Libro Illeggibile Bianco Nero Giallo is a 1956 Italian book, here issued in a 2011 off-commercial edition in the 30×24 cm format, with 50 pages, hardcover binding and Italian text.

Description from the seller

Bruno Munari. Book Illeggibile Bianco Nero Giallo 1956. Milan, Giorgio Lucini Editore, 2011. Out-of-commerce edition with copies dedicated to individuals, kindly provided by Alberto Munari. Size 30x24 cm. Editorial softcover in half cloth with a yellow hardcover cardboard folder. Facsimile of Munari's signature on the front cover of the folder and on the penultimate sheet. 50 white, black, and yellow unnumbered cards, cut in various ways to form geometric designs. In excellent condition — minimal, marginal, and negligible signs of use on the cover.

Bruno Munari (Milan, October 24, 1907 – Milan, September 30, 1998) was an Italian artist, designer, and writer.

Alongside the spatial artist Lucio Fontana, Bruno Munari established himself on the Milanese scene of the fifties and sixties; these are the years of the economic boom, during which the figure of the artist operator-visual emerged—becoming a corporate consultant and actively contributing to Italy's post-war industrial renaissance.

Munari, at a very young age, participated in Futurism, from which he distanced himself with a sense of lightness and humor, inventing the aircraft (1930), the first mobile in art history, and the useless machines (1933). In 1948, he founded the MAC (Movimento Arte Concreta) together with Gillo Dorfles, Gianni Monnet, and Atanasio Soldati. This movement acts as a coalition of Italian abstractist ideas, proposing a synthesis of the arts capable of combining traditional painting with new communication tools and demonstrating to industrialists and artists the possibility of convergence between art and technology. In 1947, he created Concavo-convesso, one of the earliest installations in art history, almost contemporary, though earlier, than the black environment presented by Lucio Fontana in 1949 at the Galleria Naviglio in Milan. This is clear evidence that the issue of art becoming environment, in which the viewer is engaged not only mentally but in a multi-sensory way, has now matured.

In 1950, he created projected painting through abstract compositions enclosed between slide glass and split light using the Polaroid filter, resulting in polarized painting in 1952, which he presented at MoMA in 1954 with the exhibition Munari's Slides. He is considered one of the protagonists of programmed and kinetic art, but eludes any definition or categorization due to the multiplicity of his activities and his great and intense creativity, which results in highly refined art.

Biography

When someone says: I can do this too, it means they know how to do it; otherwise, they would have already done it before.

(Bruno Munari, Verbale scritto, 1992)

Born in Milan to Pia Cavicchioni, a fan and handkerchief embroidery artist, and Enrico Munari, a native head waiter from Badia Polesine, Bruno Munari spent his childhood and adolescence in the paternal town of Badia Polesine, where his parents had moved to manage a hotel. In 1925, he returned to Milan to work in several graphic design studios. In 1927, he began to associate with Marinetti and the futurist movement, exhibiting with them in various shows. In 1929, Munari opened a studio for graphics and advertising, decoration, photography, and staging together with Riccardo Castagnedi, another artist from the Milanese futurist group, signing his works with the initials R + M at least until 1937. In 1930, he created what can be considered one of the first pieces of furniture in art history, known as the 'air machine,' which Munari reproduced in 1972 as a limited edition of 10 copies for the Danese editions of Milan.

In 1933, the search for moving artworks continued with useless machines, hanging objects, where all elements are in harmonious relation to each other, in terms of measurements, shapes, and weights.

During a trip to Paris in 1933, he met Louis Aragon and André Breton.

In 1934, he married Dilma Carnevali.

From 1939 to 1945, he worked as a graphic designer at the publisher Mondadori and as the art director of the magazine Tempo, simultaneously beginning to write children's books, initially conceived for his son Alberto. In 1948, together with Gillo Dorfles, Gianni Monnet, Galliano Mazzon, and Atanasio Soldati, he founded the Concrete Art Movement.

In the 1950s, his visual research led him to create negative-positive images, abstract paintings that allow the viewer to freely choose the foreground shape from the background. In 1951, he presented the arithmetic machines, where the machine's repetitive movement is interrupted by randomness through humorous interventions. Also from the 1950s are the unreadable books, where the narrative is purely visual. In 1954, using Polaroid lenses, he built kinetic art objects known as Polariscopes, which exploit the phenomenon of light decomposition for aesthetic purposes. In 1953, he presented the research 'the sea as craftsman,' recovering objects shaped by the sea, while in 1955, he created the imaginary museum of the Eolie Islands, where theoretical reconstructions of imaginary objects emerge—abstract compositions at the border between anthropology, humor, and fantasy.

In 1958, by modeling the tines of forks, he created a sign language using talking forks. In 1958, he presented travel sculptures, a revolutionary reinterpretation of the concept of sculpture, no longer monumental but portable, available to the new nomads of today's globalized world. In 1959, he created the fossils of 2000, which humorously provoke reflection on the obsolescence of modern technology.

In the 1960s, trips to Japan became increasingly frequent, as Munari felt a growing affinity for its culture, finding precise confirmations of his interest in the Zen spirit, asymmetry, design, and packaging within Japanese tradition. In 1965, in Tokyo, he designed a fountain with five drops that fall randomly at predetermined points, creating an intersection of waves, whose sounds, collected by microphones placed underwater, are amplified and played back in the square hosting the installation.

In the sixties, he dedicated himself to serial works with creations such as Aconà Biconbì, double spheres, nine spheres in a column, Tetracono (1961-1965), or Flexy (1968); to visual experiments with the photocopier (1964); to performances with the action 'show the air' (Como, 1968); to cinematic experiments with films like 'The Colors of Light' (music by Luciano Berio), 'Inox', 'Moire' (music by Pietro Grossi), 'Time in Time', 'Checkmate', and 'On Escalators' (1963-64). In fact, together with Marcello Piccardo and his five children in Cardina, on the hill of Monteolimpino in Como, between 1962 and 1972, he produced avant-garde films. From this experience, the 'Cineteca di Monteolimpino - International Center for Research Film' was born.

A Cardina, also known as 'The Hill of Cinema,' Bruno Munari lived and worked there for many summers, up until the last years of his life. His home-studio, still existing today and now the headquarters of the Cardina Association, was located right at the end of the paved road, on Via Conconi, opposite the Crotto del Lupo restaurant.

In the book 'The Cinema Hill' by Marcello Piccardo (NodoLibri, Como 1992), the experience of those years is summarized. In the story 'High Tension' (1991) by Bruno Munari, the artist describes his close relationship with the woods on the hill of Cardina.

In 1974, he explored the fractal possibilities of the curve named after the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano, a curve that Munari filled with colors for purely aesthetic purposes.

In 1977, in fulfillment of the ongoing interest in the world of childhood, it created the first children's workshop in a museum, at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

In the eighties and nineties, his creativity did not exhaust itself and he created several cycles of works: the Filipesi sculptures (1981), the graphic constructions of friends' and collectors' names (from 1982), the rotors (1989), high-voltage structures (1990), large corten steel sculptures displayed along the Naples seafront, Cesenatico, Riva del Garda, Cantù, xeror portraits (1991), and the material ideograms of trees (1993).

After numerous significant recognitions in honor of his extensive career, Munari created his last work a few months before his death at the age of 91 in his hometown.

The painter and poet Tonino Milite was his collaborator and worked in his studio for years.

Munari was the sixth among the eight greats of Milan buried in the Famedio at the Cimitero Monumentale.

Visual arts

The artist's dream is still to reach the Museum, while the designer's dream is to reach the local markets.

(Bruno Munari, artist and designer, 1971)

Munari's strictly artistic production is a volcanic array of techniques, methods, and forms, appearing in more than 200 solo exhibitions and 400 group shows.

During the fascist years, Munari worked as a graphic designer in journalism, creating covers for various magazines. He exhibited some paintings with the futurists, but as early as 1930, he created the first 'useless machines,' true abstract works developed in space that involve the surrounding environment. He dedicated himself to increasingly unconventional works, such as the 'air machine' (1930), the 'tactile board' (1931), the 'useless machines' (1933), collages (1936), the mosaic for the Milan Triennale (1936), and structures with oscillating elements (1940).

In the 1940s and 1950s, he began to outline some guidelines for his exploration.

Art as environment: Munari was among the first to conceive and anticipate installations ('Concavo-convesso', 1946) and video installations ('direct projections', 1950) and 'projections with polarized light', 1953).

Kinetic art ('Ora X' from 1945 is probably the first work of kinetic art produced in series in the history of art).

Concrete art (the 'Positive Negatives' starting from 1948)

the light (the photographs from 1950, the experiments with polarized light from 1954)

Nature and Chance ('Objects Found' from 1951, 'The Sea as Craftsman' from 1953)

The game (the 'Artist's Toys' from 1952)

the imaginary objects (the 'Unreadable writings of unknown peoples' from 1947, the 'Imaginary museum of the Eolie Islands' in Panarea from 1955, the 'Talking forks' from 1958, the 'Fossils of 2000' from 1959)

In 1949, he began creating the 'unreadable books,' books where words disappear to make space for the imagination of those who can envision other stories by reading different colored papers, tears, holes, and threads crossing the pages. The series of unreadable books continued until 1988, while in 1954, he created his fountain for the Venice Biennale.

In the 1960s, thanks to the adoption of all the new technologies available to the general public (projectors, photocopiers, film cameras), Munari's artistic activity became an encyclopedia of do-it-yourself art, where each work carried the implicit message to the viewer: 'try it yourself.' This included xerographies, studies on movement, fountains, flexible structures, optical illusions, and experimental films ('Colors in Light,' from 1963, which included music by Luciano Berio). In 1962, he organized the first exhibition of programmed art at the Olivetti store in Milan.

In 1969, Munari, concerned about the incorrect critical perception of his artistic work, which is still often confused with other genres (teaching, design, graphic design), chose art historian Miroslava Hájek to curate a selection of his most important artworks. The collection, structured chronologically, illustrates his ongoing creativity, thematic consistency, and the evolution of his aesthetic philosophy until his death.

During the seventies, given the greater interest in actual teaching and writing, artistic production in the strict sense diminished, only to resume at the end of the decade. In 1979, he was commissioned by the Teatro comunale di Firenze to create the chromatic score for the symphonic work Prometheus by Aleksandr Nikolaevič Skrjabin. The work, with its chromatic staging created in collaboration with Davide Mosconi and Piero Castiglioni, was then performed in March 1980.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Munari continued his creative exploration with 'oil on canvas' works (from 1980, re-exhibited in a personal room at the Venice Biennale in 1986), the 'filipesi' sculptures in 1981, the 'rotors' in 1989, and the 'high voltage' sculptures from 1990-91, along with large-scale public installations between 1992 and 1996, and the material ideograms 'trees' from 1993.

In recent works, the private dimension is becoming more prominent, which is reflected in the extensive production of limited edition books printed with Maurizio Corraini for friends and bibliophiles.

Collaboration with the magazine 'Domus'.

Bruno Munari, between the late 1940s and early 1950s, was overwhelmed by an explosive creativity that led to the creation of important works, including useless machines and negative-positive paintings, abstract and sign-based. All these experiments contributed, albeit with varying degrees, to the design and production of some covers for the magazine 'Domus,' which can be easily associated with the movement of Concrete Art. This movement, unlike pure abstraction, believes that the subject is the painting itself, that is, forms and colors freely invented.

Bruno Munari photographed by Federico Patellani, 1950

Concrete art is therefore that which reveals the inner nature of man or woman, human thought, sensitivity, aesthetics, the sense of balance, and everything that is part of the inner nature, just as much as the outer nature.

Concrete abstraction thus proposes autonomous forms, which are not figures of reality but autonomous realities themselves, concrete realities. Among the various covers created by the artist, numbers 357, 361, and 367 stand out, in which the central subjects are basic shapes such as squares and rectangles, arranged individually in succession lines. In all three magazines, black and white are present, paired respectively with yellow, the combination of red and green, and gray, with flat color fields that strongly evoke useless machines. Thanks to this expressive choice, the forms seem to move suspended in space, as if connected by a thin nylon thread; yet, at the same time, they appear independent of each other, contributing to the creation of an apparent movement.

Perceptual instability is therefore sought by Munari through combinations of basic shapes and opposing primary colors, aiming to go beyond any rules related to the support or materials used. However, to understand the artist's choices, it is necessary to refer to his positive-negative works. In these, each shape and every part of the composition is either in the foreground or the background depending on the viewer's interpretation. The following principles apply:

Behind the concrete forms, there is no longer any background.

- Every form within the artwork has an exact compositional value; the artwork exists at every point.

- each element that makes up the framework must be considered the subject.

There should be no posed subject in the background.

The structuring of the work based on these principles indeed results in a perceptual instability in the composition, achieved through the way the drawn lines divide it. This causes the background to be nullified in relation to the figures in the foreground.

The absence of a background is essential to achieve equality and coplanarity between the drawn forms, as the artist himself explains in the writing: 'The negative positives.'

The line is a boundary between two equivalent forms.

The figure and the background are equivalent.

A and B together in a square, or also isolated.

The resulting effect makes each shape in the work appear to move, to advance, or to retreat within the viewer's perceptual optical space, creating a chromatic dynamic and an optical instability depending on how the viewer considers each shape.

In the specific case of cover no. 357 of 'Domus,' the background is divided into vertical bands by lines of adjacent and overlapping squares, while it is divided into horizontal bands by the spacing between the squares of the same row. As just illustrated, the figure of the square is as essential in this magazine as in others, because it is the basic element with which positive and negative shapes are constructed; these appear more or less in the foreground depending on what the observer perceives, somewhat like a chessboard (although in this case, the black and white are equivalent, whereas in positive-negative images there is a disproportion of space and color). Another reason why the square plays a particularly important role in graphic production is that, thanks to its structural characteristics, it offers a harmonious skeleton on which to base artistic construction, to the extent that Munari himself considers it the principal element of every era and style.

It is also interesting to note the influence that Mondrian's painting had on Munari, in fact many of his characteristics can also be found in these compositions, such as:

the presence of elementary forms

the asymmetry of the composition

the presence of a lot of white space and emptiness.

However, the artist goes beyond Mondrian's minimalist essentialism: the negative-positive, in fact, is more of a concept than a painting. In these new works, there is no longer any sense of depth or expression, and the colors are flat; therefore, the negative-positives could be 'read' as architectures of shapes and colors. This concept is summarized by a phrase from Munari himself: 'A blue is not a sky, a green is not a meadow, even if inside us these colors evoke sensations of skies and meadows. The concrete artwork is no longer even definable within the categories of painting, sculpture, etc.: it is an object that can be hung on the wall or ceiling, or placed on the ground. Sometimes it may resemble a painting or a sculpture (in the modern sense) but has nothing in common with these.'

In this last cover, no. 361, the artist's preference for pairing complementary colors is evident: in this case, red and green are associated. This choice is not accidental but relates to the theory of negatives-positives, as Munari believes that contrasting elements can bring a particular harmony to the composition. Also worth considering is Munari's passion for Eastern culture, from which he draws the concept of Yin and Yang, representing the unity formed by the balance of two opposing, equal, and contrary forces. This unity is embodied in a dynamic disc composed of two rotating shapes in opposite directions (black/white). "Yang is the positive force: it is masculine, warmth, hardness, firmness, light, the sun, fire, red, the base of a hill, the source of a river. Yin is the negative principle: it is feminine, mysterious, soft, moist, secret, dark, ethereal, turbid, and inactive; it is the north shadow of a hill, the estuary of a river. Yang and Yin are present in all things (...). It is the balance of opposing forces: effort alternating with rest, light with darkness, yes with no."

In his/her retina, an excess of red light causes green images (…)

Industrial design

Modular and disassemblable structure in various configurations. The habitable structure is a living space, an almost invisible support for your microcosm. It weighs 51 kilograms and can carry up to twenty people.

(Bruno Munari, artist and designer, 1971)

One day I went to a sock factory to see if they could make me a lamp. - We don't make lamps, sir. - You'll see that you will make them. And so it was.

Bruno Munari, about the Falkland lamp

As a freelance professional, Munari designed several dozen pieces of furniture from 1935 to 1992, including tables, armchairs, bookshelves, lamps, ashtrays, carts, and combinable furniture, most of which were for Bruno Danese. It was precisely in the field of industrial design that Munari created his most successful objects, such as the monkey toy Zizi (1953), the foldable 'travel sculpture' designed to recreate a familiar aesthetic environment in anonymous hotel rooms (1958), the Maiorca pen holder and the Cubo ashtray (1958), the Falkland lamp, the Abitacolo (1971), and the Dattilo lamp (1978).

In addition to designing furniture objects, Munari also created window displays (La Rinascente, 1953), color combinations for car paints (Montecatini, 1954), display elements (Danese, 1960, Robots, 1980), and even fabrics (Assia, 1982). At the age of 90, he signed his last work, the 'Tempo libero' Swatch watch, in 1997.

Books and editorial graphics

Munari's editorial production spans seventy years, from 1929 to 1998, and includes actual books (technical essays, poetry, manuals, 'artistic' books, children's books, school texts), advertising pamphlet books for various industries, covers, dust jackets, illustrations, and photographs. In all his works, there is a strong experimental drive that pushes him to explore unusual and innovative forms, from layout design, unreadable books without text, to the pre-hypertext of popular science works like the famous Artista e designer (1971). In addition to his extensive work as an author, numerous covers and illustrations for books by Gianni Rodari, Nico Orengo, and others are also part of his contributions.

To assess the impact that Munari's design work had on the image of culture in Italy, one can take the work for the publisher Einaudi as an example. Munari, together with Max Huber, created the graphics for the series Piccola Biblioteca (with the colored square at the top), Nuova Universale (with red horizontal stripes), Collezione di poesia (with verses on a white background on the cover), Nuovo Politecnico (with the central red square), Paperbacks (with the central blue square), Letteratura, Centopagine, and the multi-volume works (Storia d'Italia, Enciclopedia, Letteratura italiana, Storia dell'arte italiana) between 1962 and 1972. Among other highly successful graphic projects, there are the Nuova Biblioteca di Cultura and the Works of Marx-Engels for Editori Riuniti, as well as two essay series for Bompiani.

In 1974, together with Bob Noorda, Pino Tovaglia, and Roberto Sambonet, he designed the logo and corporate identity of the Lombardy Region.

Educational games and workshops

There is always some old lady who faces the children making scary faces and saying silly things in an informal language full of 'ciccì', 'coccò', and 'piciupaciù'. Usually, the children look at these people, who have aged in vain, with great severity; they don't understand what they want and go back to their simple and very serious games.

(Bruno Munari, Art as a Craft, 1966)

From 1988 to 1992, Munari personally collaborated on the educational workshops at the Luigi Pecci Center for Contemporary Art in Prato, training the internal staff, namely Barbara Conti and Riccardo Farinelli, who continued and coordinated the museum workshops consistently until 2014, when the Pecci's management decided to abolish the Munarian educational activities.

The wooden constructions 'Architecture Box' for Castelletti (1945)

The Gatto Meo toys (1949) and the Zizì Monkey (1953) for Pirelli

From 1959 to 1976, various games for Danese (Direct Projections, ABC, Maze, Plus and Minus, Put the Leaves, Structures, Transformations, Sign Language, Images of Reality)

Le mani guardano (1979), Milan

First children's workshop at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan (1977)

Laboratory 'Playing with Art' at the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza (1981) in collaboration with Gian Carlo Bojani.

The children's laboratory at Kodomo no shiro (Castle of Children) in Tokyo (1985)

Playing with Art (1987) Palazzo Reale, Milan

Playing with nature (1988) Natural History Museum, Milan

Playing with Art (1988) Luigi Pecci Centre for Contemporary Art, Prato, permanent workshops

Find Childhood (1989) Fiera Milano, Workshops dedicated to the elderly, Milan

A flower with love (1991) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Playing with the photocopier (1991) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

The 'Read Book,' a written quilt that is both a book and a bed (1993) by Interflex.

Lab-Lib (1992) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Playing with the needle (1994) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Tactile Boards (1995) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Awards and Recognitions

Compasso d'Oro Award from the Industrial Design Association (1954, 1955, 1979)

Gold medal from the Milan Triennale for unreadable books (1957)

Andersen Award as Best Children's Author (1974)

Honorable Mention from the New York Academy of Sciences (1974)

Bologna Fair Graphic Award for Children (1984)

Prize from the Japan Design Foundation, 'for the intense human value of its design' (1985)

LEGO Award for its outstanding contribution to the development of creativity in children (1986)

Ulma's 'Spiel Gut' award (1971, 1973, 1987)

Feltrinelli Prize ex aequo for Graphics (1988), awarded by the Accademia dei Lincei

Honorary degree in architecture from the University of Genoa (1989)

Honorary Member of the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera - Marconi Award (1992)

Knight of the Grand Cross (1994)

'Compasso d'oro' Lifetime Achievement Award (1995)

Honorary Member of Harvard University

Bruno Munari in museums

MAGA Art Museum of Gallarate (VA)

MART - Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto (Province of Trento)

Selected exhibitions

Bruno Munari. Everything, (2023), edited by Marco Meneguzzo, Fondazione Magnani-Rocca, Mamiano di Traversetolo, Parma.

PataAsemica, (2023), edited by Duccio Scheggi, Marco Garofalo, and Giuseppe Calandriello, Stecca 3, Milan

Bruno Munari, (2022), edited by Manuel Fontán Del Junco, Marco Meneguzzo, and Aida Capa, Fundación Juan March, Madrid

Tra Munari and Rodari, (2020), Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome

XXXV Venice Biennale, (1970), Venice

XXXIII Venice Biennale, (1966), Venice

Books by Bruno Munari

Design and visual communication

Tree

the very slow explosion

of a seed

(Bruno Munari, 'Bifront Phenomena', 1993)

Palette of graphic possibilities, with Ricas - Muggiani publisher (1935)

Photographic chronicles by Munari - Domus (1944)

Supplement to the Italian dictionary - Carpano (1958)

Munari's forks - La Giostra (1958)

The discovery of the square - Scheiwiller (1960)

Theorems on Art - Scheiwiller (1961)

Italian shop windows - Editrice L'ufficio moderno (1961)

Good design - Scheiwiller (1963)

The discovery of the circle - Scheiwiller (1964)

Art as a profession - Laterza (1966)

Design and Visual Communication - Laterza (1968)

Artist and designer - Laterza (1971)

Obvious code - Einaudi (1971)

The discovery of the triangle - Zanichelli (1976)

Fantasia - Laterza (1977)

Original xerographies - Zanichelli (1977)

Guide to woodworking - Mondadori (1978)

From one thing, another arises - Laterza (1981)

The children's workshop at Brera - Zanichelli (1981)

The children's workshop at the Faenza International Museum of Ceramics - Zanichelli (1981)

Ciccì Coccò - FotoSelex (1982)

A Light Show - Zanichelli (1984)

The tactile laboratories - Zanichelli (1985)

Surprise direction, with Mario De Biasi - Cordani (1986)

Games and graphics - Municipality of Soncino (1990)

The Dictionary of Italian Gestures - Adnkronos Libri (1994)

The Children's Castle in Tokyo - Einaudi (1995)

Habitable Space 1968-1996 - Stampa Alternativa (1996)

Supplement to the Italian Dictionary, Mantova, Italy, Corraini. (2014)

Research books

In this category, the few poetry books are grouped together with all 'd'artista' or otherwise non-conventional volumes, often printed in limited editions or outside the commercial trade.

Unreadable books - Salto Bookstore (1949)

Unreadable book no. 8 - (1951)

Unintelligible book no. 12 - (1951)

Unreadable book no. 15 - (1951)

Unreadable book - (1952)

An unreadable quadrat-print - Hilversum (1953)

Six Lines in Motion (1958)

Unreadable book no. XXV - (1959)

Unreadable book with interchangeable pages - (1960)

Unreadable book no. 25 (1964)

Unreadable Book 1966 - Galleria dell'Obelisco (1966)

Unreadable Book N.Y.1 - The Museum of Modern Art (1967)

Let's look each other in the eyes - Giorgio Lucini publisher (1970)

Unreadable book MN1 - Corraini (1984)

The rule and the case - Mano (1984)

The negatives-positives 1950 - Corraini (1986)

Munari 80 one millimeter from me - Scheiwiller (1987)

Unintelligible book MN1 - Corraini (1988)

Unreadable book 1988-2 - Arcadia (1988)

Simultaneity of Opposites - Corraini (1989)

High Tension - Vismara Arte (1990)

Unreadable book NA-1 - Beppe Morra (1990)

Breach of the rule - (1990)

Friends of Sincron - Sincron Gallery (1991)

Secret Rite - Laboratory 66 (1991)

Metamorphosis of plastics - Milan Triennial (1991)

In your face! Exercises in Style - Corraini (1992)

Unreadable book MN3. Capricious Moon - Corraini (1992)

Greetings and kisses. Escape exercises - Corraini (1992)

Journey into Imagination - Corraini (1992)

Thinking confuses ideas - Corraini (1992)

Recycled aphorisms - Pulcinoelefante (1991)

Written report - Il Melangolo (1992)

Bifront Phenomena - Etra/Arte (1993)

Illegible Book MN4 - Corraini (1994)

Tactile board - Alpha Magical (1994)

Bruno Munari Group Exhibition - Corraini (1994)

Adults and children in unexplored areas - Corraini (1994)

Most affectionate best wishes - NodoLibri (1994)

Aphorisms - Pulcinoelefante (1994)

Illegible Book MN5 - Corraini (1995)

The sea as a craftsman - Corraini (1995)

Emotions - Corraini (1995)

About nougats - Pulcinoelefante (1996)

Before the drawing - Corraini (1996)

Who is Bruno Munari? - Corraini (1996)

Segno & segno - Etra/arte (1996)

Books for children

Every book is read.

but not every bed is also a book

(Bruno Munari, in Domus no. 760, 1994)

Movo: flying models and detached parts - Grafitalia (1940)

World air water earth - (1940)

Munari's Machines - Einaudi (1942)

Abecedario di Munari - Einaudi (1942)

Box of Architecture - Castelletti (1945)

Never satisfied - Mondadori (1945)

The man of the truck - Mondadori (1945)

Knock knock - Mondadori (1945)

The Green Magician - Mondadori (1945)

Stories of Three Little Birds - Mondadori (1945)

The Animal Seller - Mondadori (1945)

Gigi searches for his hat - Mondadori (1945)

What is the clock - Editrice Piccoli (1947)

What is the thermometer - Editrice Piccoli (1947)

Meo the crazy cat - Pirelli (1948)

Water, Earth, Air - Orlando Cibelli Publisher (1952)

In the dark night - Muggiani (1956)

The Alphabet Book - Einaudi (1960)

Bruno Munari's ABC - World Publishing Company (1960)

Bruno Munari's Zoo - World Publishing Company (1963)

The cake in heaven - Einaudi (1966)

In the fog of Milan - Emme editions (1968)

From afar, it was an island - Emme editions (1971)

The Little Bird Tic Tic, with Emanuele Luzzati - Einaudi (1972)

Cappuccetto Verde - Einaudi (1972)

Yellow Little Riding Hood - Einaudi (1972)

Where are we going?, with Mari Carmen Diaz - Emme editions (1973)

A flower with love - Einaudi (1973)

A country of plastic, with Ettore Maiotti - Einaudi (1973)

Rose in the Salad - Einaudi (1974)

Black Panther, by Franca Capalbi - Einaudi (1975)

The example of the greats, with Florenzio Corona - Einaudi (1976)

The clever hummingbird, with Paola Bianchetto - Einaudi (1977)

Drawing a tree - Zanichelli (1977)

Drawing the Sun - Zanichelli (1980)

I prelibri (12 books) - Danese (1980)

Red Little Riding Hood, Green, Yellow, Blue, and White - Einaudi (1981)

Tantagente - The Museum of Modern Art (1983)

The blackbird lost its beak, with Giovanni Belgrano - Danese (1987).

The fairy tale of fairy tales - Publi-Paolini (1994)

The Frog Romilda - Corraini (1997)

The Yellow Magician - Corraini (1997)

Good night to everyone - Corraini (1997)

Cappuccetto bianco - Corraini (1999)

Books for school

Tec 90 - Minerva Italica (1990)

The eye and the art - Ghisetti e Corvi (1992)

Methods, models, and techniques - Minerva Italica (1993)

Sounds and ideas for improvisation - Ricordi (1995)

Modulart - Atlas (1999)

Advertising and industry

Linoleum, with Ricas - Società del linoleum (1938)

The idea is in the thread - Bassetti (1964)

Xerography - Rank Xerox (1972)

Lucini Alphabet - Lucini (1987)

Watch out for the light - Osram (1990)

Film about Bruno Munari

The hill of cinema - Andrea Piccardo (1995)

In the studio with Munari - Andrea Piccardo (2007)

Music albums for Bruno Munari

Repaired opera. A tribute to Bruno Munari (2012) - Filippo Paolini aka Økapi and the Aldo Kapi Orchestra

The Turin-based music collective 'Lastanzadigreta' released the album 'Inutile Machines' in 2020, inspired by Munari's useless machines.

Bruno Munari. Book Illeggibile Bianco Nero Giallo 1956. Milan, Giorgio Lucini Editore, 2011. Out-of-commerce edition with copies dedicated to individuals, kindly provided by Alberto Munari. Size 30x24 cm. Editorial softcover in half cloth with a yellow hardcover cardboard folder. Facsimile of Munari's signature on the front cover of the folder and on the penultimate sheet. 50 white, black, and yellow unnumbered cards, cut in various ways to form geometric designs. In excellent condition — minimal, marginal, and negligible signs of use on the cover.

Bruno Munari (Milan, October 24, 1907 – Milan, September 30, 1998) was an Italian artist, designer, and writer.

Alongside the spatial artist Lucio Fontana, Bruno Munari established himself on the Milanese scene of the fifties and sixties; these are the years of the economic boom, during which the figure of the artist operator-visual emerged—becoming a corporate consultant and actively contributing to Italy's post-war industrial renaissance.

Munari, at a very young age, participated in Futurism, from which he distanced himself with a sense of lightness and humor, inventing the aircraft (1930), the first mobile in art history, and the useless machines (1933). In 1948, he founded the MAC (Movimento Arte Concreta) together with Gillo Dorfles, Gianni Monnet, and Atanasio Soldati. This movement acts as a coalition of Italian abstractist ideas, proposing a synthesis of the arts capable of combining traditional painting with new communication tools and demonstrating to industrialists and artists the possibility of convergence between art and technology. In 1947, he created Concavo-convesso, one of the earliest installations in art history, almost contemporary, though earlier, than the black environment presented by Lucio Fontana in 1949 at the Galleria Naviglio in Milan. This is clear evidence that the issue of art becoming environment, in which the viewer is engaged not only mentally but in a multi-sensory way, has now matured.

In 1950, he created projected painting through abstract compositions enclosed between slide glass and split light using the Polaroid filter, resulting in polarized painting in 1952, which he presented at MoMA in 1954 with the exhibition Munari's Slides. He is considered one of the protagonists of programmed and kinetic art, but eludes any definition or categorization due to the multiplicity of his activities and his great and intense creativity, which results in highly refined art.

Biography

When someone says: I can do this too, it means they know how to do it; otherwise, they would have already done it before.

(Bruno Munari, Verbale scritto, 1992)

Born in Milan to Pia Cavicchioni, a fan and handkerchief embroidery artist, and Enrico Munari, a native head waiter from Badia Polesine, Bruno Munari spent his childhood and adolescence in the paternal town of Badia Polesine, where his parents had moved to manage a hotel. In 1925, he returned to Milan to work in several graphic design studios. In 1927, he began to associate with Marinetti and the futurist movement, exhibiting with them in various shows. In 1929, Munari opened a studio for graphics and advertising, decoration, photography, and staging together with Riccardo Castagnedi, another artist from the Milanese futurist group, signing his works with the initials R + M at least until 1937. In 1930, he created what can be considered one of the first pieces of furniture in art history, known as the 'air machine,' which Munari reproduced in 1972 as a limited edition of 10 copies for the Danese editions of Milan.

In 1933, the search for moving artworks continued with useless machines, hanging objects, where all elements are in harmonious relation to each other, in terms of measurements, shapes, and weights.

During a trip to Paris in 1933, he met Louis Aragon and André Breton.

In 1934, he married Dilma Carnevali.

From 1939 to 1945, he worked as a graphic designer at the publisher Mondadori and as the art director of the magazine Tempo, simultaneously beginning to write children's books, initially conceived for his son Alberto. In 1948, together with Gillo Dorfles, Gianni Monnet, Galliano Mazzon, and Atanasio Soldati, he founded the Concrete Art Movement.

In the 1950s, his visual research led him to create negative-positive images, abstract paintings that allow the viewer to freely choose the foreground shape from the background. In 1951, he presented the arithmetic machines, where the machine's repetitive movement is interrupted by randomness through humorous interventions. Also from the 1950s are the unreadable books, where the narrative is purely visual. In 1954, using Polaroid lenses, he built kinetic art objects known as Polariscopes, which exploit the phenomenon of light decomposition for aesthetic purposes. In 1953, he presented the research 'the sea as craftsman,' recovering objects shaped by the sea, while in 1955, he created the imaginary museum of the Eolie Islands, where theoretical reconstructions of imaginary objects emerge—abstract compositions at the border between anthropology, humor, and fantasy.

In 1958, by modeling the tines of forks, he created a sign language using talking forks. In 1958, he presented travel sculptures, a revolutionary reinterpretation of the concept of sculpture, no longer monumental but portable, available to the new nomads of today's globalized world. In 1959, he created the fossils of 2000, which humorously provoke reflection on the obsolescence of modern technology.

In the 1960s, trips to Japan became increasingly frequent, as Munari felt a growing affinity for its culture, finding precise confirmations of his interest in the Zen spirit, asymmetry, design, and packaging within Japanese tradition. In 1965, in Tokyo, he designed a fountain with five drops that fall randomly at predetermined points, creating an intersection of waves, whose sounds, collected by microphones placed underwater, are amplified and played back in the square hosting the installation.

In the sixties, he dedicated himself to serial works with creations such as Aconà Biconbì, double spheres, nine spheres in a column, Tetracono (1961-1965), or Flexy (1968); to visual experiments with the photocopier (1964); to performances with the action 'show the air' (Como, 1968); to cinematic experiments with films like 'The Colors of Light' (music by Luciano Berio), 'Inox', 'Moire' (music by Pietro Grossi), 'Time in Time', 'Checkmate', and 'On Escalators' (1963-64). In fact, together with Marcello Piccardo and his five children in Cardina, on the hill of Monteolimpino in Como, between 1962 and 1972, he produced avant-garde films. From this experience, the 'Cineteca di Monteolimpino - International Center for Research Film' was born.

A Cardina, also known as 'The Hill of Cinema,' Bruno Munari lived and worked there for many summers, up until the last years of his life. His home-studio, still existing today and now the headquarters of the Cardina Association, was located right at the end of the paved road, on Via Conconi, opposite the Crotto del Lupo restaurant.

In the book 'The Cinema Hill' by Marcello Piccardo (NodoLibri, Como 1992), the experience of those years is summarized. In the story 'High Tension' (1991) by Bruno Munari, the artist describes his close relationship with the woods on the hill of Cardina.

In 1974, he explored the fractal possibilities of the curve named after the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano, a curve that Munari filled with colors for purely aesthetic purposes.

In 1977, in fulfillment of the ongoing interest in the world of childhood, it created the first children's workshop in a museum, at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

In the eighties and nineties, his creativity did not exhaust itself and he created several cycles of works: the Filipesi sculptures (1981), the graphic constructions of friends' and collectors' names (from 1982), the rotors (1989), high-voltage structures (1990), large corten steel sculptures displayed along the Naples seafront, Cesenatico, Riva del Garda, Cantù, xeror portraits (1991), and the material ideograms of trees (1993).

After numerous significant recognitions in honor of his extensive career, Munari created his last work a few months before his death at the age of 91 in his hometown.

The painter and poet Tonino Milite was his collaborator and worked in his studio for years.

Munari was the sixth among the eight greats of Milan buried in the Famedio at the Cimitero Monumentale.

Visual arts

The artist's dream is still to reach the Museum, while the designer's dream is to reach the local markets.

(Bruno Munari, artist and designer, 1971)

Munari's strictly artistic production is a volcanic array of techniques, methods, and forms, appearing in more than 200 solo exhibitions and 400 group shows.

During the fascist years, Munari worked as a graphic designer in journalism, creating covers for various magazines. He exhibited some paintings with the futurists, but as early as 1930, he created the first 'useless machines,' true abstract works developed in space that involve the surrounding environment. He dedicated himself to increasingly unconventional works, such as the 'air machine' (1930), the 'tactile board' (1931), the 'useless machines' (1933), collages (1936), the mosaic for the Milan Triennale (1936), and structures with oscillating elements (1940).

In the 1940s and 1950s, he began to outline some guidelines for his exploration.

Art as environment: Munari was among the first to conceive and anticipate installations ('Concavo-convesso', 1946) and video installations ('direct projections', 1950) and 'projections with polarized light', 1953).

Kinetic art ('Ora X' from 1945 is probably the first work of kinetic art produced in series in the history of art).

Concrete art (the 'Positive Negatives' starting from 1948)

the light (the photographs from 1950, the experiments with polarized light from 1954)

Nature and Chance ('Objects Found' from 1951, 'The Sea as Craftsman' from 1953)

The game (the 'Artist's Toys' from 1952)

the imaginary objects (the 'Unreadable writings of unknown peoples' from 1947, the 'Imaginary museum of the Eolie Islands' in Panarea from 1955, the 'Talking forks' from 1958, the 'Fossils of 2000' from 1959)

In 1949, he began creating the 'unreadable books,' books where words disappear to make space for the imagination of those who can envision other stories by reading different colored papers, tears, holes, and threads crossing the pages. The series of unreadable books continued until 1988, while in 1954, he created his fountain for the Venice Biennale.

In the 1960s, thanks to the adoption of all the new technologies available to the general public (projectors, photocopiers, film cameras), Munari's artistic activity became an encyclopedia of do-it-yourself art, where each work carried the implicit message to the viewer: 'try it yourself.' This included xerographies, studies on movement, fountains, flexible structures, optical illusions, and experimental films ('Colors in Light,' from 1963, which included music by Luciano Berio). In 1962, he organized the first exhibition of programmed art at the Olivetti store in Milan.

In 1969, Munari, concerned about the incorrect critical perception of his artistic work, which is still often confused with other genres (teaching, design, graphic design), chose art historian Miroslava Hájek to curate a selection of his most important artworks. The collection, structured chronologically, illustrates his ongoing creativity, thematic consistency, and the evolution of his aesthetic philosophy until his death.

During the seventies, given the greater interest in actual teaching and writing, artistic production in the strict sense diminished, only to resume at the end of the decade. In 1979, he was commissioned by the Teatro comunale di Firenze to create the chromatic score for the symphonic work Prometheus by Aleksandr Nikolaevič Skrjabin. The work, with its chromatic staging created in collaboration with Davide Mosconi and Piero Castiglioni, was then performed in March 1980.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Munari continued his creative exploration with 'oil on canvas' works (from 1980, re-exhibited in a personal room at the Venice Biennale in 1986), the 'filipesi' sculptures in 1981, the 'rotors' in 1989, and the 'high voltage' sculptures from 1990-91, along with large-scale public installations between 1992 and 1996, and the material ideograms 'trees' from 1993.

In recent works, the private dimension is becoming more prominent, which is reflected in the extensive production of limited edition books printed with Maurizio Corraini for friends and bibliophiles.

Collaboration with the magazine 'Domus'.

Bruno Munari, between the late 1940s and early 1950s, was overwhelmed by an explosive creativity that led to the creation of important works, including useless machines and negative-positive paintings, abstract and sign-based. All these experiments contributed, albeit with varying degrees, to the design and production of some covers for the magazine 'Domus,' which can be easily associated with the movement of Concrete Art. This movement, unlike pure abstraction, believes that the subject is the painting itself, that is, forms and colors freely invented.

Bruno Munari photographed by Federico Patellani, 1950

Concrete art is therefore that which reveals the inner nature of man or woman, human thought, sensitivity, aesthetics, the sense of balance, and everything that is part of the inner nature, just as much as the outer nature.

Concrete abstraction thus proposes autonomous forms, which are not figures of reality but autonomous realities themselves, concrete realities. Among the various covers created by the artist, numbers 357, 361, and 367 stand out, in which the central subjects are basic shapes such as squares and rectangles, arranged individually in succession lines. In all three magazines, black and white are present, paired respectively with yellow, the combination of red and green, and gray, with flat color fields that strongly evoke useless machines. Thanks to this expressive choice, the forms seem to move suspended in space, as if connected by a thin nylon thread; yet, at the same time, they appear independent of each other, contributing to the creation of an apparent movement.

Perceptual instability is therefore sought by Munari through combinations of basic shapes and opposing primary colors, aiming to go beyond any rules related to the support or materials used. However, to understand the artist's choices, it is necessary to refer to his positive-negative works. In these, each shape and every part of the composition is either in the foreground or the background depending on the viewer's interpretation. The following principles apply:

Behind the concrete forms, there is no longer any background.

- Every form within the artwork has an exact compositional value; the artwork exists at every point.

- each element that makes up the framework must be considered the subject.

There should be no posed subject in the background.

The structuring of the work based on these principles indeed results in a perceptual instability in the composition, achieved through the way the drawn lines divide it. This causes the background to be nullified in relation to the figures in the foreground.

The absence of a background is essential to achieve equality and coplanarity between the drawn forms, as the artist himself explains in the writing: 'The negative positives.'

The line is a boundary between two equivalent forms.

The figure and the background are equivalent.

A and B together in a square, or also isolated.

The resulting effect makes each shape in the work appear to move, to advance, or to retreat within the viewer's perceptual optical space, creating a chromatic dynamic and an optical instability depending on how the viewer considers each shape.

In the specific case of cover no. 357 of 'Domus,' the background is divided into vertical bands by lines of adjacent and overlapping squares, while it is divided into horizontal bands by the spacing between the squares of the same row. As just illustrated, the figure of the square is as essential in this magazine as in others, because it is the basic element with which positive and negative shapes are constructed; these appear more or less in the foreground depending on what the observer perceives, somewhat like a chessboard (although in this case, the black and white are equivalent, whereas in positive-negative images there is a disproportion of space and color). Another reason why the square plays a particularly important role in graphic production is that, thanks to its structural characteristics, it offers a harmonious skeleton on which to base artistic construction, to the extent that Munari himself considers it the principal element of every era and style.

It is also interesting to note the influence that Mondrian's painting had on Munari, in fact many of his characteristics can also be found in these compositions, such as:

the presence of elementary forms

the asymmetry of the composition

the presence of a lot of white space and emptiness.

However, the artist goes beyond Mondrian's minimalist essentialism: the negative-positive, in fact, is more of a concept than a painting. In these new works, there is no longer any sense of depth or expression, and the colors are flat; therefore, the negative-positives could be 'read' as architectures of shapes and colors. This concept is summarized by a phrase from Munari himself: 'A blue is not a sky, a green is not a meadow, even if inside us these colors evoke sensations of skies and meadows. The concrete artwork is no longer even definable within the categories of painting, sculpture, etc.: it is an object that can be hung on the wall or ceiling, or placed on the ground. Sometimes it may resemble a painting or a sculpture (in the modern sense) but has nothing in common with these.'

In this last cover, no. 361, the artist's preference for pairing complementary colors is evident: in this case, red and green are associated. This choice is not accidental but relates to the theory of negatives-positives, as Munari believes that contrasting elements can bring a particular harmony to the composition. Also worth considering is Munari's passion for Eastern culture, from which he draws the concept of Yin and Yang, representing the unity formed by the balance of two opposing, equal, and contrary forces. This unity is embodied in a dynamic disc composed of two rotating shapes in opposite directions (black/white). "Yang is the positive force: it is masculine, warmth, hardness, firmness, light, the sun, fire, red, the base of a hill, the source of a river. Yin is the negative principle: it is feminine, mysterious, soft, moist, secret, dark, ethereal, turbid, and inactive; it is the north shadow of a hill, the estuary of a river. Yang and Yin are present in all things (...). It is the balance of opposing forces: effort alternating with rest, light with darkness, yes with no."

In his/her retina, an excess of red light causes green images (…)

Industrial design

Modular and disassemblable structure in various configurations. The habitable structure is a living space, an almost invisible support for your microcosm. It weighs 51 kilograms and can carry up to twenty people.

(Bruno Munari, artist and designer, 1971)

One day I went to a sock factory to see if they could make me a lamp. - We don't make lamps, sir. - You'll see that you will make them. And so it was.

Bruno Munari, about the Falkland lamp

As a freelance professional, Munari designed several dozen pieces of furniture from 1935 to 1992, including tables, armchairs, bookshelves, lamps, ashtrays, carts, and combinable furniture, most of which were for Bruno Danese. It was precisely in the field of industrial design that Munari created his most successful objects, such as the monkey toy Zizi (1953), the foldable 'travel sculpture' designed to recreate a familiar aesthetic environment in anonymous hotel rooms (1958), the Maiorca pen holder and the Cubo ashtray (1958), the Falkland lamp, the Abitacolo (1971), and the Dattilo lamp (1978).

In addition to designing furniture objects, Munari also created window displays (La Rinascente, 1953), color combinations for car paints (Montecatini, 1954), display elements (Danese, 1960, Robots, 1980), and even fabrics (Assia, 1982). At the age of 90, he signed his last work, the 'Tempo libero' Swatch watch, in 1997.

Books and editorial graphics

Munari's editorial production spans seventy years, from 1929 to 1998, and includes actual books (technical essays, poetry, manuals, 'artistic' books, children's books, school texts), advertising pamphlet books for various industries, covers, dust jackets, illustrations, and photographs. In all his works, there is a strong experimental drive that pushes him to explore unusual and innovative forms, from layout design, unreadable books without text, to the pre-hypertext of popular science works like the famous Artista e designer (1971). In addition to his extensive work as an author, numerous covers and illustrations for books by Gianni Rodari, Nico Orengo, and others are also part of his contributions.

To assess the impact that Munari's design work had on the image of culture in Italy, one can take the work for the publisher Einaudi as an example. Munari, together with Max Huber, created the graphics for the series Piccola Biblioteca (with the colored square at the top), Nuova Universale (with red horizontal stripes), Collezione di poesia (with verses on a white background on the cover), Nuovo Politecnico (with the central red square), Paperbacks (with the central blue square), Letteratura, Centopagine, and the multi-volume works (Storia d'Italia, Enciclopedia, Letteratura italiana, Storia dell'arte italiana) between 1962 and 1972. Among other highly successful graphic projects, there are the Nuova Biblioteca di Cultura and the Works of Marx-Engels for Editori Riuniti, as well as two essay series for Bompiani.

In 1974, together with Bob Noorda, Pino Tovaglia, and Roberto Sambonet, he designed the logo and corporate identity of the Lombardy Region.

Educational games and workshops

There is always some old lady who faces the children making scary faces and saying silly things in an informal language full of 'ciccì', 'coccò', and 'piciupaciù'. Usually, the children look at these people, who have aged in vain, with great severity; they don't understand what they want and go back to their simple and very serious games.

(Bruno Munari, Art as a Craft, 1966)

From 1988 to 1992, Munari personally collaborated on the educational workshops at the Luigi Pecci Center for Contemporary Art in Prato, training the internal staff, namely Barbara Conti and Riccardo Farinelli, who continued and coordinated the museum workshops consistently until 2014, when the Pecci's management decided to abolish the Munarian educational activities.

The wooden constructions 'Architecture Box' for Castelletti (1945)

The Gatto Meo toys (1949) and the Zizì Monkey (1953) for Pirelli

From 1959 to 1976, various games for Danese (Direct Projections, ABC, Maze, Plus and Minus, Put the Leaves, Structures, Transformations, Sign Language, Images of Reality)

Le mani guardano (1979), Milan

First children's workshop at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan (1977)

Laboratory 'Playing with Art' at the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza (1981) in collaboration with Gian Carlo Bojani.

The children's laboratory at Kodomo no shiro (Castle of Children) in Tokyo (1985)

Playing with Art (1987) Palazzo Reale, Milan

Playing with nature (1988) Natural History Museum, Milan

Playing with Art (1988) Luigi Pecci Centre for Contemporary Art, Prato, permanent workshops

Find Childhood (1989) Fiera Milano, Workshops dedicated to the elderly, Milan

A flower with love (1991) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Playing with the photocopier (1991) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

The 'Read Book,' a written quilt that is both a book and a bed (1993) by Interflex.

Lab-Lib (1992) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Playing with the needle (1994) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Tactile Boards (1995) Playing with Munari at Beba Restelli's Laboratory

Awards and Recognitions

Compasso d'Oro Award from the Industrial Design Association (1954, 1955, 1979)

Gold medal from the Milan Triennale for unreadable books (1957)

Andersen Award as Best Children's Author (1974)

Honorable Mention from the New York Academy of Sciences (1974)

Bologna Fair Graphic Award for Children (1984)

Prize from the Japan Design Foundation, 'for the intense human value of its design' (1985)

LEGO Award for its outstanding contribution to the development of creativity in children (1986)

Ulma's 'Spiel Gut' award (1971, 1973, 1987)

Feltrinelli Prize ex aequo for Graphics (1988), awarded by the Accademia dei Lincei

Honorary degree in architecture from the University of Genoa (1989)

Honorary Member of the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera - Marconi Award (1992)

Knight of the Grand Cross (1994)

'Compasso d'oro' Lifetime Achievement Award (1995)

Honorary Member of Harvard University

Bruno Munari in museums

MAGA Art Museum of Gallarate (VA)

MART - Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto (Province of Trento)

Selected exhibitions

Bruno Munari. Everything, (2023), edited by Marco Meneguzzo, Fondazione Magnani-Rocca, Mamiano di Traversetolo, Parma.

PataAsemica, (2023), edited by Duccio Scheggi, Marco Garofalo, and Giuseppe Calandriello, Stecca 3, Milan

Bruno Munari, (2022), edited by Manuel Fontán Del Junco, Marco Meneguzzo, and Aida Capa, Fundación Juan March, Madrid

Tra Munari and Rodari, (2020), Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome

XXXV Venice Biennale, (1970), Venice

XXXIII Venice Biennale, (1966), Venice

Books by Bruno Munari

Design and visual communication

Tree

the very slow explosion

of a seed

(Bruno Munari, 'Bifront Phenomena', 1993)

Palette of graphic possibilities, with Ricas - Muggiani publisher (1935)

Photographic chronicles by Munari - Domus (1944)

Supplement to the Italian dictionary - Carpano (1958)

Munari's forks - La Giostra (1958)

The discovery of the square - Scheiwiller (1960)

Theorems on Art - Scheiwiller (1961)

Italian shop windows - Editrice L'ufficio moderno (1961)

Good design - Scheiwiller (1963)

The discovery of the circle - Scheiwiller (1964)

Art as a profession - Laterza (1966)

Design and Visual Communication - Laterza (1968)

Artist and designer - Laterza (1971)

Obvious code - Einaudi (1971)

The discovery of the triangle - Zanichelli (1976)

Fantasia - Laterza (1977)

Original xerographies - Zanichelli (1977)

Guide to woodworking - Mondadori (1978)

From one thing, another arises - Laterza (1981)

The children's workshop at Brera - Zanichelli (1981)

The children's workshop at the Faenza International Museum of Ceramics - Zanichelli (1981)

Ciccì Coccò - FotoSelex (1982)

A Light Show - Zanichelli (1984)

The tactile laboratories - Zanichelli (1985)

Surprise direction, with Mario De Biasi - Cordani (1986)

Games and graphics - Municipality of Soncino (1990)

The Dictionary of Italian Gestures - Adnkronos Libri (1994)

The Children's Castle in Tokyo - Einaudi (1995)

Habitable Space 1968-1996 - Stampa Alternativa (1996)

Supplement to the Italian Dictionary, Mantova, Italy, Corraini. (2014)

Research books

In this category, the few poetry books are grouped together with all 'd'artista' or otherwise non-conventional volumes, often printed in limited editions or outside the commercial trade.

Unreadable books - Salto Bookstore (1949)

Unreadable book no. 8 - (1951)

Unintelligible book no. 12 - (1951)

Unreadable book no. 15 - (1951)

Unreadable book - (1952)

An unreadable quadrat-print - Hilversum (1953)

Six Lines in Motion (1958)

Unreadable book no. XXV - (1959)

Unreadable book with interchangeable pages - (1960)

Unreadable book no. 25 (1964)

Unreadable Book 1966 - Galleria dell'Obelisco (1966)

Unreadable Book N.Y.1 - The Museum of Modern Art (1967)

Let's look each other in the eyes - Giorgio Lucini publisher (1970)

Unreadable book MN1 - Corraini (1984)

The rule and the case - Mano (1984)

The negatives-positives 1950 - Corraini (1986)

Munari 80 one millimeter from me - Scheiwiller (1987)

Unintelligible book MN1 - Corraini (1988)

Unreadable book 1988-2 - Arcadia (1988)

Simultaneity of Opposites - Corraini (1989)

High Tension - Vismara Arte (1990)

Unreadable book NA-1 - Beppe Morra (1990)

Breach of the rule - (1990)

Friends of Sincron - Sincron Gallery (1991)

Secret Rite - Laboratory 66 (1991)

Metamorphosis of plastics - Milan Triennial (1991)

In your face! Exercises in Style - Corraini (1992)

Unreadable book MN3. Capricious Moon - Corraini (1992)

Greetings and kisses. Escape exercises - Corraini (1992)

Journey into Imagination - Corraini (1992)

Thinking confuses ideas - Corraini (1992)

Recycled aphorisms - Pulcinoelefante (1991)

Written report - Il Melangolo (1992)

Bifront Phenomena - Etra/Arte (1993)

Illegible Book MN4 - Corraini (1994)

Tactile board - Alpha Magical (1994)

Bruno Munari Group Exhibition - Corraini (1994)

Adults and children in unexplored areas - Corraini (1994)

Most affectionate best wishes - NodoLibri (1994)

Aphorisms - Pulcinoelefante (1994)

Illegible Book MN5 - Corraini (1995)

The sea as a craftsman - Corraini (1995)

Emotions - Corraini (1995)

About nougats - Pulcinoelefante (1996)

Before the drawing - Corraini (1996)

Who is Bruno Munari? - Corraini (1996)

Segno & segno - Etra/arte (1996)

Books for children

Every book is read.

but not every bed is also a book

(Bruno Munari, in Domus no. 760, 1994)

Movo: flying models and detached parts - Grafitalia (1940)

World air water earth - (1940)

Munari's Machines - Einaudi (1942)

Abecedario di Munari - Einaudi (1942)

Box of Architecture - Castelletti (1945)

Never satisfied - Mondadori (1945)

The man of the truck - Mondadori (1945)

Knock knock - Mondadori (1945)

The Green Magician - Mondadori (1945)

Stories of Three Little Birds - Mondadori (1945)

The Animal Seller - Mondadori (1945)

Gigi searches for his hat - Mondadori (1945)

What is the clock - Editrice Piccoli (1947)

What is the thermometer - Editrice Piccoli (1947)

Meo the crazy cat - Pirelli (1948)

Water, Earth, Air - Orlando Cibelli Publisher (1952)

In the dark night - Muggiani (1956)

The Alphabet Book - Einaudi (1960)

Bruno Munari's ABC - World Publishing Company (1960)

Bruno Munari's Zoo - World Publishing Company (1963)

The cake in heaven - Einaudi (1966)

In the fog of Milan - Emme editions (1968)

From afar, it was an island - Emme editions (1971)

The Little Bird Tic Tic, with Emanuele Luzzati - Einaudi (1972)

Cappuccetto Verde - Einaudi (1972)

Yellow Little Riding Hood - Einaudi (1972)

Where are we going?, with Mari Carmen Diaz - Emme editions (1973)

A flower with love - Einaudi (1973)

A country of plastic, with Ettore Maiotti - Einaudi (1973)

Rose in the Salad - Einaudi (1974)

Black Panther, by Franca Capalbi - Einaudi (1975)

The example of the greats, with Florenzio Corona - Einaudi (1976)

The clever hummingbird, with Paola Bianchetto - Einaudi (1977)

Drawing a tree - Zanichelli (1977)

Drawing the Sun - Zanichelli (1980)

I prelibri (12 books) - Danese (1980)

Red Little Riding Hood, Green, Yellow, Blue, and White - Einaudi (1981)

Tantagente - The Museum of Modern Art (1983)

The blackbird lost its beak, with Giovanni Belgrano - Danese (1987).

The fairy tale of fairy tales - Publi-Paolini (1994)

The Frog Romilda - Corraini (1997)

The Yellow Magician - Corraini (1997)

Good night to everyone - Corraini (1997)

Cappuccetto bianco - Corraini (1999)

Books for school

Tec 90 - Minerva Italica (1990)

The eye and the art - Ghisetti e Corvi (1992)

Methods, models, and techniques - Minerva Italica (1993)

Sounds and ideas for improvisation - Ricordi (1995)

Modulart - Atlas (1999)

Advertising and industry

Linoleum, with Ricas - Società del linoleum (1938)

The idea is in the thread - Bassetti (1964)

Xerography - Rank Xerox (1972)

Lucini Alphabet - Lucini (1987)

Watch out for the light - Osram (1990)

Film about Bruno Munari

The hill of cinema - Andrea Piccardo (1995)

In the studio with Munari - Andrea Piccardo (2007)

Music albums for Bruno Munari

Repaired opera. A tribute to Bruno Munari (2012) - Filippo Paolini aka Økapi and the Aldo Kapi Orchestra

The Turin-based music collective 'Lastanzadigreta' released the album 'Inutile Machines' in 2020, inspired by Munari's useless machines.