Gio Ponti - Lo Stile. - 1941

Bidder 3124 Bidder 3124 | €2 |

|---|

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 124625 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

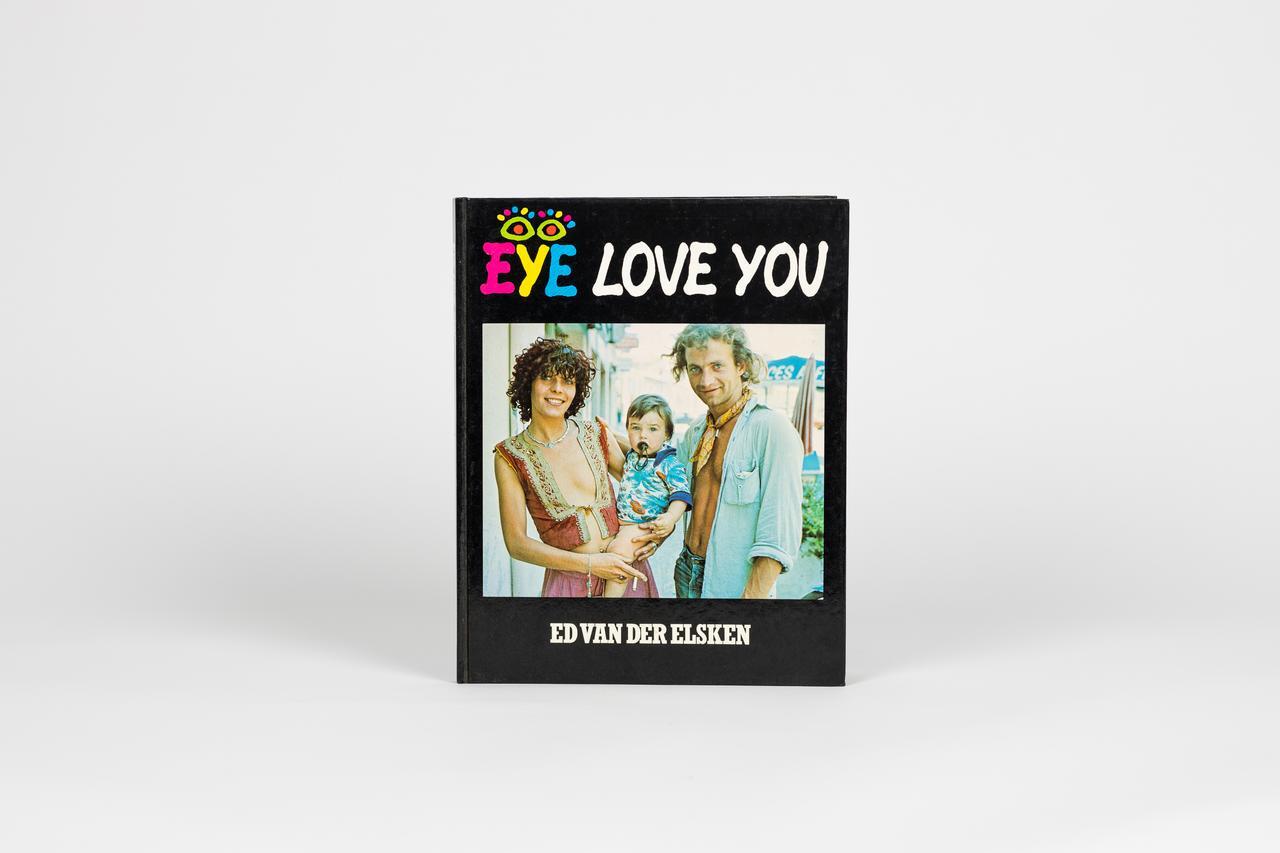

Gio Ponti is the author of Lo Stile, a 1941 Italian magazine in 1st edition with 67 pages, in Italian, bound in a soft cover, measuring 32 × 24 cm and in good condition.

Description from the seller

Original magazine. Style in the home and interior design. Director Gio Ponti. No. 11, 1941. Beautiful cover by Gianlica (Gio Ponti, Enrico Bo, Lina Bo, Carlo Pagani). In this issue: Olivetti advertising, An environment by Franco Buzzi, An environment by architect Ignazio Gardella, Gio Ponti: The house colored by new fabrics, A page of De Chirico, Milan and the eighth Triennale, etc. In excellent condition - normal signs of aging and minor defects. Auction without reserve.

The magazine 'Stile', founded and directed by Gio Ponti from 1941 to 1947 for Garzanti editions, was an important publication that explored architecture, furniture, decorative arts, and painting, promoting an idea of elegant and accessible modernity during a difficult historical period. Ponti described the magazine as 'of ideas, of life, of the future, and above all, of art.' The goal was to highlight works of architecture and furniture, as well as drawings, painting, and sculpture, with a focus on the concept of 'style' as a guiding principle for modern life. The publication served as a 'found' diary of Ponti's thoughts during those years, revealing nuances of his creative journey in a transitional moment, away from his previous experience with the magazine Domus. Architecture and Reconstruction: During the years of World War II and the post-war period, the magazine focused heavily on reconstruction and the house of the future, proposing modern, functional, and lightweight housing solutions. Decorative Arts and Furniture: In addition to architecture, Stile gave ample space to decorative arts and furniture, promoting Italian design and collaboration with companies that would become synonymous with Made in Italy. Eclectic Approach: The magazine was distinguished by a comprehensive approach to the arts, embracing both architecture and painting and sculpture, reflecting Ponti's vision of unified art present in every aspect of life.

Illustrations: The issues were richly illustrated with photographs and color plates, often featuring illustrations by renowned artists like Sassu, to provide a strong and inspiring visual impact.

Promotion of Modernity: Ponti used the magazine as a platform to shape the public's taste and promote an idea of modernity that is open, elegant, and never aggressive, emphasizing functionality without sacrificing beauty.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Opere

Industrial design

1923-1929 Porcelain pieces for Richard-Ginori

1927 Pewter and silver objects for Christofle

1930 Large pieces in crystal for Fontana

1930 large aluminum table presented at the IV Triennale di Monza

1930 Designs for printed fabrics for De Angeli-Frua, Milan.

1930 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari

1930 Cutlery and other objects for Krupp Italiana

1931 lamps for fountain, Milan

1931 Three libraries for the Opera Omnia of D'Annunzio

1931 Furniture for Turri, Varedo (Milan)

1934 Brustio Furniture, Milan

1935 Cellina Furniture, Milan

1936 Small Furniture, Milan

1936 Arredamento Pozzi, Milan

1936 Watches for Boselli, Milan

1936 scroll armchair presented at the VI Triennale di Milano, produced by Casa e Giardino, then (1946) by Cassina and (1969) by Montina.

1936 Furniture for Home and Garden, Milan

1938 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari, Milan

1938 Chairs for Home and Garden

1938 Steel swivel seat for Kardex

Interiors of the Settebello Train

In 1948, he collaborated with Alberto Rosselli and Antonio Fornaroli in creating 'La Cornuta,' the first horizontal boiler espresso machine produced by 'La Pavoni S.p.A.'

In 1949, Collabora collaborated with Visa mechanical workshops in Voghera to create the sewing machine 'Visetta.'

In 1952, collaborated with AVE to create electrical switches.

1955 cutlery for Arthur Krupp

1957 Superleggera Chair for Cassina

1963 Scooter Brio for Ducati

1971 small armchair seat for Walter Ponti

Carlo Mollino (Turin, May 6, 1905 – Turin, August 27, 1973) was an Italian architect, designer, and photographer.

Biography

Born in Turin, the only son of engineer Eugenio Mollino, he completed his studies from elementary to high school at the Collegio San Giuseppe. In 1925, he enrolled in the Faculty of Engineering and, after a year, transferred to the Royal Higher School of Architecture at the Albertina Academy of Turin, which later became the Faculty of Architecture at the Polytechnic University of Turin, where he graduated in July 1931.

Mollino was, in addition to being an architect and designer, also an airplane and race car driver, writer, and photographer. An excellent skier, he became a ski instructor in 1942 and after the war, president of the CoScuMa (commission of ski schools and teachers) of F.I.S.I. In 1951, he wrote the treatise 'Introduction to downhill skiing,' from whose pages emerges his entire restless, imaginative, and eccentric personality.

After publishing the volumes Architecture, Art, and Technique in 1948, he won the competition for full professor in 1953 and obtained the chair of Architectural Composition, which he held until his death. In 1957, he participated in the organizing committee of the 11th Milan Triennale.

Mollino died suddenly in August 1973, while he was still active in his studio.

Architecture

In 1930, still not graduated, he designed the holiday house in Forte dei Marmi and received the 'G. Pistono' award for Architecture. Between 1933 and 1948, while working in his father's studio, he participated in numerous competitions. He won the first competition for the headquarters of the Cuneo Farmers' Federation, the first prize in the contest for the Fascio di Voghera house, and, in collaboration with sculptor Umberto Mastroianni, the first prize in the contest for the Monument to the Fallen for Freedom of Turin (also known as the Monument to the Partisan), which was placed in the Campo della Gloria at the General Cemetery of Turin.

Between 1936 and 1939, he built, in collaboration with engineer Vittorio Baudi di Selve, the building of the Società Ippica Torinese, considered his masterpiece, constructed in Turin on Corso Dante and demolished in 1960. It was an work that broke with the past and distanced itself from regime architecture, rejecting the dictates of rationalism and drawing inspiration from Alvar Aalto and Erich Mendelsohn.

In love with the mountains, he also designed some mountain buildings, including the House of the Sun in Cervinia, the arrival station of the Furggen cable car, and the Slittovia of Lago Nero near Sauze d'Oulx. The latter chalet, built between 1946 and 1947, features, towards the mountain, a large terrace that boldly projects from the main volume, combining modern forms and construction techniques with the traditional materials used. The building underwent a radical restoration in 2001, necessary after decades of abandonment and vandalism.

In 1952, he designed the Rai Arturo Toscanini Auditorium on via Rossini in Turin, which was subject to a controversial restoration carried out in 2006 that radically altered its original structure.

In the first half of the sixties, he directed the team of professionals responsible for designing the INA-Casa neighborhood in Corso Sebastopoli in Turin and received the second prize in the competition for the Turin Workers' Palace, which was later won by Pier Luigi Nervi, despite the competition rules requiring a building with a single volume without columns in the central part.

In 1964, he participated in the competition for the Turin Chamber of Commerce, where he ranked first, and in the competition for the Cagliari Municipal Theatre, where he placed third.

In the final years of his career, from 1965 to 1973, he designed and built the two Turin buildings that made him famous: the Chamber of Commerce building on San Francesco da Paola Street/Piazzale Valdo Fusi and he participated in the project of the new Teatro Regio (rebuilt after the 1936 fire), which was inaugurated in 1973. Shortly before his death, he completed the projects for the offices of the energy company AEM (now Iren) on Corso Svizzera in Turin, and he participated in competitions for the FIAT Business Center in Candiolo and for the Club Méditerranée in Sestrière.

Design

In the 1940s, Mollino began his activity as an interior designer and designer.

Furniture, often produced as one-of-a-kind pieces or in limited series, combines the use of artisanal construction techniques with the experimentation of new materials and technologies, such as bent layered plywood.

In particular, the 'cold bending' technique of plywood made its chairs, tables, and armchairs famous in the early 1950s.

The aesthetics that derive from it cannot be directly attributed to any particular artistic movement, and, moreover, it is certainly incorrect to place Mollinian works within an exclusively Futurist context.

Carlo Mollino drew from his passions, such as skiing and aviation, to reproduce some forms in architecture and interior design, proposing highly innovative shapes that are disconnected from mass production: the 'Reale' table (1949), aeronautically inspired, as well as the 'Cadma' lamp (1947), which recalls the shape of a propeller, and the 'Gilda' armchair (1947), which anticipates the hi-tech style. In almost all his works, his interest in speed and movement is evident. His furniture is mainly recognizable for its sinuous, almost erotic lines that clearly evoke the female body, which the artist loved to photograph, having chosen to lead a life in which his passions were constantly involved in his work.

His figure as a creative was constantly outside the box, earning him the nickname 'designer senza industria'.

Deeply fascinated by nature, Mollino reinterpreted its forms within his artistic production, skillfully reworking them and blending them with elements of Modernism, Art Nouveau, Surrealism, Baroque, and Rococo.

In 1963, on New Year's Eve, Carlo Mollino created the walking dragon, a sculpture in folded paper decorated by himself. The various specimens, equipped with a bobbin for the thread and an instruction booklet, are all numbered and titled.

Original magazine. Style in the home and interior design. Director Gio Ponti. No. 11, 1941. Beautiful cover by Gianlica (Gio Ponti, Enrico Bo, Lina Bo, Carlo Pagani). In this issue: Olivetti advertising, An environment by Franco Buzzi, An environment by architect Ignazio Gardella, Gio Ponti: The house colored by new fabrics, A page of De Chirico, Milan and the eighth Triennale, etc. In excellent condition - normal signs of aging and minor defects. Auction without reserve.

The magazine 'Stile', founded and directed by Gio Ponti from 1941 to 1947 for Garzanti editions, was an important publication that explored architecture, furniture, decorative arts, and painting, promoting an idea of elegant and accessible modernity during a difficult historical period. Ponti described the magazine as 'of ideas, of life, of the future, and above all, of art.' The goal was to highlight works of architecture and furniture, as well as drawings, painting, and sculpture, with a focus on the concept of 'style' as a guiding principle for modern life. The publication served as a 'found' diary of Ponti's thoughts during those years, revealing nuances of his creative journey in a transitional moment, away from his previous experience with the magazine Domus. Architecture and Reconstruction: During the years of World War II and the post-war period, the magazine focused heavily on reconstruction and the house of the future, proposing modern, functional, and lightweight housing solutions. Decorative Arts and Furniture: In addition to architecture, Stile gave ample space to decorative arts and furniture, promoting Italian design and collaboration with companies that would become synonymous with Made in Italy. Eclectic Approach: The magazine was distinguished by a comprehensive approach to the arts, embracing both architecture and painting and sculpture, reflecting Ponti's vision of unified art present in every aspect of life.

Illustrations: The issues were richly illustrated with photographs and color plates, often featuring illustrations by renowned artists like Sassu, to provide a strong and inspiring visual impact.

Promotion of Modernity: Ponti used the magazine as a platform to shape the public's taste and promote an idea of modernity that is open, elegant, and never aggressive, emphasizing functionality without sacrificing beauty.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Opere

Industrial design

1923-1929 Porcelain pieces for Richard-Ginori

1927 Pewter and silver objects for Christofle

1930 Large pieces in crystal for Fontana

1930 large aluminum table presented at the IV Triennale di Monza

1930 Designs for printed fabrics for De Angeli-Frua, Milan.

1930 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari

1930 Cutlery and other objects for Krupp Italiana

1931 lamps for fountain, Milan

1931 Three libraries for the Opera Omnia of D'Annunzio

1931 Furniture for Turri, Varedo (Milan)

1934 Brustio Furniture, Milan

1935 Cellina Furniture, Milan

1936 Small Furniture, Milan

1936 Arredamento Pozzi, Milan

1936 Watches for Boselli, Milan

1936 scroll armchair presented at the VI Triennale di Milano, produced by Casa e Giardino, then (1946) by Cassina and (1969) by Montina.

1936 Furniture for Home and Garden, Milan

1938 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari, Milan

1938 Chairs for Home and Garden

1938 Steel swivel seat for Kardex

Interiors of the Settebello Train

In 1948, he collaborated with Alberto Rosselli and Antonio Fornaroli in creating 'La Cornuta,' the first horizontal boiler espresso machine produced by 'La Pavoni S.p.A.'

In 1949, Collabora collaborated with Visa mechanical workshops in Voghera to create the sewing machine 'Visetta.'

In 1952, collaborated with AVE to create electrical switches.

1955 cutlery for Arthur Krupp

1957 Superleggera Chair for Cassina

1963 Scooter Brio for Ducati

1971 small armchair seat for Walter Ponti

Carlo Mollino (Turin, May 6, 1905 – Turin, August 27, 1973) was an Italian architect, designer, and photographer.

Biography

Born in Turin, the only son of engineer Eugenio Mollino, he completed his studies from elementary to high school at the Collegio San Giuseppe. In 1925, he enrolled in the Faculty of Engineering and, after a year, transferred to the Royal Higher School of Architecture at the Albertina Academy of Turin, which later became the Faculty of Architecture at the Polytechnic University of Turin, where he graduated in July 1931.

Mollino was, in addition to being an architect and designer, also an airplane and race car driver, writer, and photographer. An excellent skier, he became a ski instructor in 1942 and after the war, president of the CoScuMa (commission of ski schools and teachers) of F.I.S.I. In 1951, he wrote the treatise 'Introduction to downhill skiing,' from whose pages emerges his entire restless, imaginative, and eccentric personality.

After publishing the volumes Architecture, Art, and Technique in 1948, he won the competition for full professor in 1953 and obtained the chair of Architectural Composition, which he held until his death. In 1957, he participated in the organizing committee of the 11th Milan Triennale.

Mollino died suddenly in August 1973, while he was still active in his studio.

Architecture

In 1930, still not graduated, he designed the holiday house in Forte dei Marmi and received the 'G. Pistono' award for Architecture. Between 1933 and 1948, while working in his father's studio, he participated in numerous competitions. He won the first competition for the headquarters of the Cuneo Farmers' Federation, the first prize in the contest for the Fascio di Voghera house, and, in collaboration with sculptor Umberto Mastroianni, the first prize in the contest for the Monument to the Fallen for Freedom of Turin (also known as the Monument to the Partisan), which was placed in the Campo della Gloria at the General Cemetery of Turin.

Between 1936 and 1939, he built, in collaboration with engineer Vittorio Baudi di Selve, the building of the Società Ippica Torinese, considered his masterpiece, constructed in Turin on Corso Dante and demolished in 1960. It was an work that broke with the past and distanced itself from regime architecture, rejecting the dictates of rationalism and drawing inspiration from Alvar Aalto and Erich Mendelsohn.

In love with the mountains, he also designed some mountain buildings, including the House of the Sun in Cervinia, the arrival station of the Furggen cable car, and the Slittovia of Lago Nero near Sauze d'Oulx. The latter chalet, built between 1946 and 1947, features, towards the mountain, a large terrace that boldly projects from the main volume, combining modern forms and construction techniques with the traditional materials used. The building underwent a radical restoration in 2001, necessary after decades of abandonment and vandalism.

In 1952, he designed the Rai Arturo Toscanini Auditorium on via Rossini in Turin, which was subject to a controversial restoration carried out in 2006 that radically altered its original structure.

In the first half of the sixties, he directed the team of professionals responsible for designing the INA-Casa neighborhood in Corso Sebastopoli in Turin and received the second prize in the competition for the Turin Workers' Palace, which was later won by Pier Luigi Nervi, despite the competition rules requiring a building with a single volume without columns in the central part.

In 1964, he participated in the competition for the Turin Chamber of Commerce, where he ranked first, and in the competition for the Cagliari Municipal Theatre, where he placed third.

In the final years of his career, from 1965 to 1973, he designed and built the two Turin buildings that made him famous: the Chamber of Commerce building on San Francesco da Paola Street/Piazzale Valdo Fusi and he participated in the project of the new Teatro Regio (rebuilt after the 1936 fire), which was inaugurated in 1973. Shortly before his death, he completed the projects for the offices of the energy company AEM (now Iren) on Corso Svizzera in Turin, and he participated in competitions for the FIAT Business Center in Candiolo and for the Club Méditerranée in Sestrière.

Design

In the 1940s, Mollino began his activity as an interior designer and designer.

Furniture, often produced as one-of-a-kind pieces or in limited series, combines the use of artisanal construction techniques with the experimentation of new materials and technologies, such as bent layered plywood.

In particular, the 'cold bending' technique of plywood made its chairs, tables, and armchairs famous in the early 1950s.

The aesthetics that derive from it cannot be directly attributed to any particular artistic movement, and, moreover, it is certainly incorrect to place Mollinian works within an exclusively Futurist context.

Carlo Mollino drew from his passions, such as skiing and aviation, to reproduce some forms in architecture and interior design, proposing highly innovative shapes that are disconnected from mass production: the 'Reale' table (1949), aeronautically inspired, as well as the 'Cadma' lamp (1947), which recalls the shape of a propeller, and the 'Gilda' armchair (1947), which anticipates the hi-tech style. In almost all his works, his interest in speed and movement is evident. His furniture is mainly recognizable for its sinuous, almost erotic lines that clearly evoke the female body, which the artist loved to photograph, having chosen to lead a life in which his passions were constantly involved in his work.

His figure as a creative was constantly outside the box, earning him the nickname 'designer senza industria'.

Deeply fascinated by nature, Mollino reinterpreted its forms within his artistic production, skillfully reworking them and blending them with elements of Modernism, Art Nouveau, Surrealism, Baroque, and Rococo.

In 1963, on New Year's Eve, Carlo Mollino created the walking dragon, a sculpture in folded paper decorated by himself. The various specimens, equipped with a bobbin for the thread and an instruction booklet, are all numbered and titled.