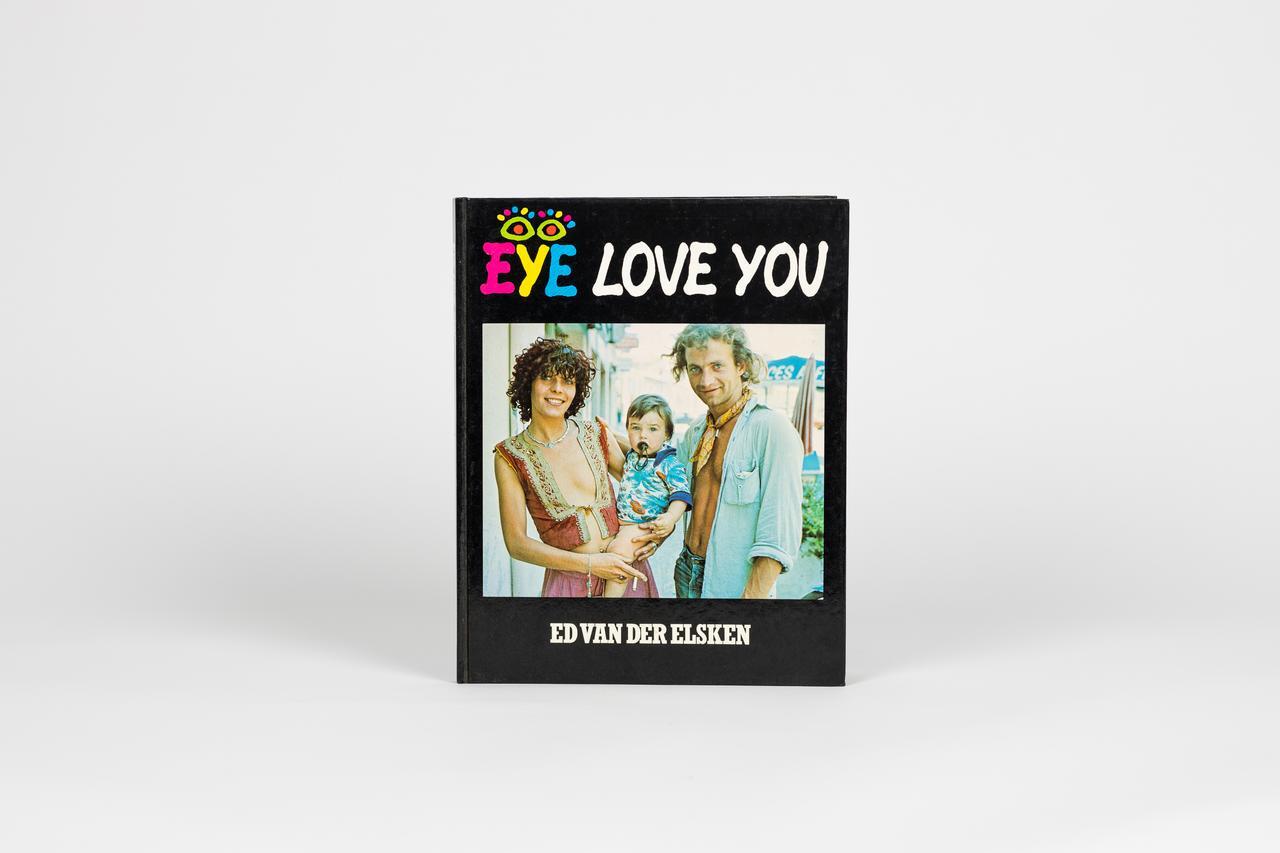

Lisa Licitra Ponti - Gio' Ponti L'opera - 1990

Studied history and managed a large online book catalogue with 13 years' antiquarian bookshop experience.

Bidder 3251 Bidder 3251 | €19 | |

|---|---|---|

Bidder 9416 Bidder 9416 | €10 |

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 122385 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

Lisa Licitra Ponti is the author/illustrator of Gio Ponti L'opera, a 1990 first edition in Italian, hardcover with 297 pages and black-and-white and colour illustrations, noting a creased dust jacket and a private ownership stamp.

Description from the seller

Lisa Licitra Ponti, Gio Ponti The Work. Preface by Germano Celant. Leonardo, 1990. Canvas, dust jacket, 297 pages. Black and white and color illustrations. First edition. Creases on the dust jacket. A private ownership stamp.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Biography

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Opere

Industrial design

1923-1929 Porcelain pieces for Richard-Ginori

1927 Pewter and silver objects for Christofle

1930 Large pieces in crystal for Fontana

1930 large aluminum table presented at the IV Triennale di Monza

1930 Designs for printed fabrics for De Angeli-Frua, Milan.

1930 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari

1930 Cutlery and other objects for Krupp Italiana

1931 lamps for fountain, Milan

1931 Three libraries for the Opera Omnia of D'Annunzio

1931 Furniture for Turri, Varedo (Milan)

1934 Brustio Furniture, Milan

1935 Cellina Furniture, Milan

1936 Small Furniture, Milan

1936 Arredamento Pozzi, Milan

1936 Watches for Boselli, Milan

1936 scroll armchair presented at the VI Triennale di Milano, produced by Casa e Giardino, then (1946) by Cassina and (1969) by Montina.

1936 Furniture for Home and Garden, Milan

1938 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari, Milan

1938 Chairs for Home and Garden

1938 Steel swivel seat for Kardex

Interiors of the Settebello Train

In 1948, he collaborated with Alberto Rosselli and Antonio Fornaroli in creating 'La Cornuta,' the first horizontal boiler espresso machine produced by 'La Pavoni S.p.A.'

In 1949, Collabora collaborated with Visa mechanical workshops in Voghera to create the sewing machine 'Visetta.'

In 1952, collaborated with AVE to create electrical switches.

1955 cutlery for Arthur Krupp

1957 Superleggera Chair for Cassina

1963 Scooter Brio for Ducati

1971 small armchair seat for Walter Ponti

Germano Lucio Celant (Genoa, September 11, 1940 – Milan, April 29, 2020) was an Italian art critic and artistic director.

Biography

He studied at the University of Genoa, where he was a student of Eugenio Battisti.

In 1967, he coined the term 'arte povera' to refer to a group of Italian artists: Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, and Emilio Prini, exhibited in the first show at Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa, which went on to achieve great international success in subsequent years. Also at La Bertesca in Genoa, he presented Im-Spazio (Bignardi, Ceroli, Icaro, Mambor, Mattiacci, Tacchi) concurrently. According to the critic's presentation in the catalog, these artists operated within a 'new design dimension that aims to understand the space of the image, no longer as a container but as a field of space-visual forces. Their works feature an open structuring of visual fragments, forming Im-Spazio as an open circulation space, in real time [...] that acts with and on the viewer'.

Celant outlined the theory and the characteristics of the movement through exhibitions and writings such as Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, and Land Art of 1970.

After the Off Media exhibition, held in Bari in 1977, he began collaborating with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, of which he later became senior curator.

At the Guggenheim, in 1994, the exhibition Italian Metamorphosis 1943-1968 was staged, aiming to bring Italian art closer to American culture. The intention to internationalize Italian art had already characterized exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1981), in London (1989), and at Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1989).

In 1996, he curated the first edition of the Florence Art and Fashion Biennale, highlighting a concept of art in constant evolution, closely connected with contemporary culture understood as a dynamic expression of global creativity. In 1997, he was appointed director of the 47th Venice Art Biennale.

Contributor to notable magazines such as L'Espresso and Interni, Celant, after creating the major exhibition Arti & Architettura in Genoa (2004), served from 1995 to 2014 as director and subsequently as artistic and scientific superintendent of the Fondazione Prada in Milan; from 2005, he was curator of the Fondazione Aldo Rossi in Milan and from 2008 of the Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova in Venice. Additionally, he organized the Arts & Foods exhibition at the Triennale di Milano during Expo 2015.

The substantial fee of 750,000 euros, awarded by Expo 2015 to the Genoese critic for the curatorship and artistic direction of the Food in Art thematic area in 2015, immediately sparked controversy: art critic Demetrio Paparoni appealed to Milan's mayor Giuliano Pisapia against the exorbitant amount, considering that the fee allocated to the director of the last Visual Arts Biennale, Massimiliano Gioni, as well as his successor Okwui Enwezor, would have been 'just' 120,000 euros. From the accusation, Celant defended himself, asserting that the total amount would also include the remuneration of the general contractor of the entire initiative, the staff, and taxes, given that Expo lacked its own internal organizational structure.

In 2016, he was the Project Manager of Christo's work The Floating Piers on Lake Iseo.

Lisa Licitra Ponti, Gio Ponti The Work. Preface by Germano Celant. Leonardo, 1990. Canvas, dust jacket, 297 pages. Black and white and color illustrations. First edition. Creases on the dust jacket. A private ownership stamp.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Biography

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Opere

Industrial design

1923-1929 Porcelain pieces for Richard-Ginori

1927 Pewter and silver objects for Christofle

1930 Large pieces in crystal for Fontana

1930 large aluminum table presented at the IV Triennale di Monza

1930 Designs for printed fabrics for De Angeli-Frua, Milan.

1930 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari

1930 Cutlery and other objects for Krupp Italiana

1931 lamps for fountain, Milan

1931 Three libraries for the Opera Omnia of D'Annunzio

1931 Furniture for Turri, Varedo (Milan)

1934 Brustio Furniture, Milan

1935 Cellina Furniture, Milan

1936 Small Furniture, Milan

1936 Arredamento Pozzi, Milan

1936 Watches for Boselli, Milan

1936 scroll armchair presented at the VI Triennale di Milano, produced by Casa e Giardino, then (1946) by Cassina and (1969) by Montina.

1936 Furniture for Home and Garden, Milan

1938 Fabrics for Vittorio Ferrari, Milan

1938 Chairs for Home and Garden

1938 Steel swivel seat for Kardex

Interiors of the Settebello Train

In 1948, he collaborated with Alberto Rosselli and Antonio Fornaroli in creating 'La Cornuta,' the first horizontal boiler espresso machine produced by 'La Pavoni S.p.A.'

In 1949, Collabora collaborated with Visa mechanical workshops in Voghera to create the sewing machine 'Visetta.'

In 1952, collaborated with AVE to create electrical switches.

1955 cutlery for Arthur Krupp

1957 Superleggera Chair for Cassina

1963 Scooter Brio for Ducati

1971 small armchair seat for Walter Ponti

Germano Lucio Celant (Genoa, September 11, 1940 – Milan, April 29, 2020) was an Italian art critic and artistic director.

Biography

He studied at the University of Genoa, where he was a student of Eugenio Battisti.

In 1967, he coined the term 'arte povera' to refer to a group of Italian artists: Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, and Emilio Prini, exhibited in the first show at Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa, which went on to achieve great international success in subsequent years. Also at La Bertesca in Genoa, he presented Im-Spazio (Bignardi, Ceroli, Icaro, Mambor, Mattiacci, Tacchi) concurrently. According to the critic's presentation in the catalog, these artists operated within a 'new design dimension that aims to understand the space of the image, no longer as a container but as a field of space-visual forces. Their works feature an open structuring of visual fragments, forming Im-Spazio as an open circulation space, in real time [...] that acts with and on the viewer'.

Celant outlined the theory and the characteristics of the movement through exhibitions and writings such as Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, and Land Art of 1970.

After the Off Media exhibition, held in Bari in 1977, he began collaborating with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, of which he later became senior curator.

At the Guggenheim, in 1994, the exhibition Italian Metamorphosis 1943-1968 was staged, aiming to bring Italian art closer to American culture. The intention to internationalize Italian art had already characterized exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1981), in London (1989), and at Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1989).

In 1996, he curated the first edition of the Florence Art and Fashion Biennale, highlighting a concept of art in constant evolution, closely connected with contemporary culture understood as a dynamic expression of global creativity. In 1997, he was appointed director of the 47th Venice Art Biennale.

Contributor to notable magazines such as L'Espresso and Interni, Celant, after creating the major exhibition Arti & Architettura in Genoa (2004), served from 1995 to 2014 as director and subsequently as artistic and scientific superintendent of the Fondazione Prada in Milan; from 2005, he was curator of the Fondazione Aldo Rossi in Milan and from 2008 of the Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova in Venice. Additionally, he organized the Arts & Foods exhibition at the Triennale di Milano during Expo 2015.

The substantial fee of 750,000 euros, awarded by Expo 2015 to the Genoese critic for the curatorship and artistic direction of the Food in Art thematic area in 2015, immediately sparked controversy: art critic Demetrio Paparoni appealed to Milan's mayor Giuliano Pisapia against the exorbitant amount, considering that the fee allocated to the director of the last Visual Arts Biennale, Massimiliano Gioni, as well as his successor Okwui Enwezor, would have been 'just' 120,000 euros. From the accusation, Celant defended himself, asserting that the total amount would also include the remuneration of the general contractor of the entire initiative, the staff, and taxes, given that Expo lacked its own internal organizational structure.

In 2016, he was the Project Manager of Christo's work The Floating Piers on Lake Iseo.