Gio Ponti - Gio Ponti. L'arte si innamora dell'industria. - 1995

Bidder 3569 Bidder 3569 | €96 | |

|---|---|---|

Bidder 3085 Bidder 3085 | €91 | |

Bidder 2677 Bidder 2677 | €86 | |

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123759 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

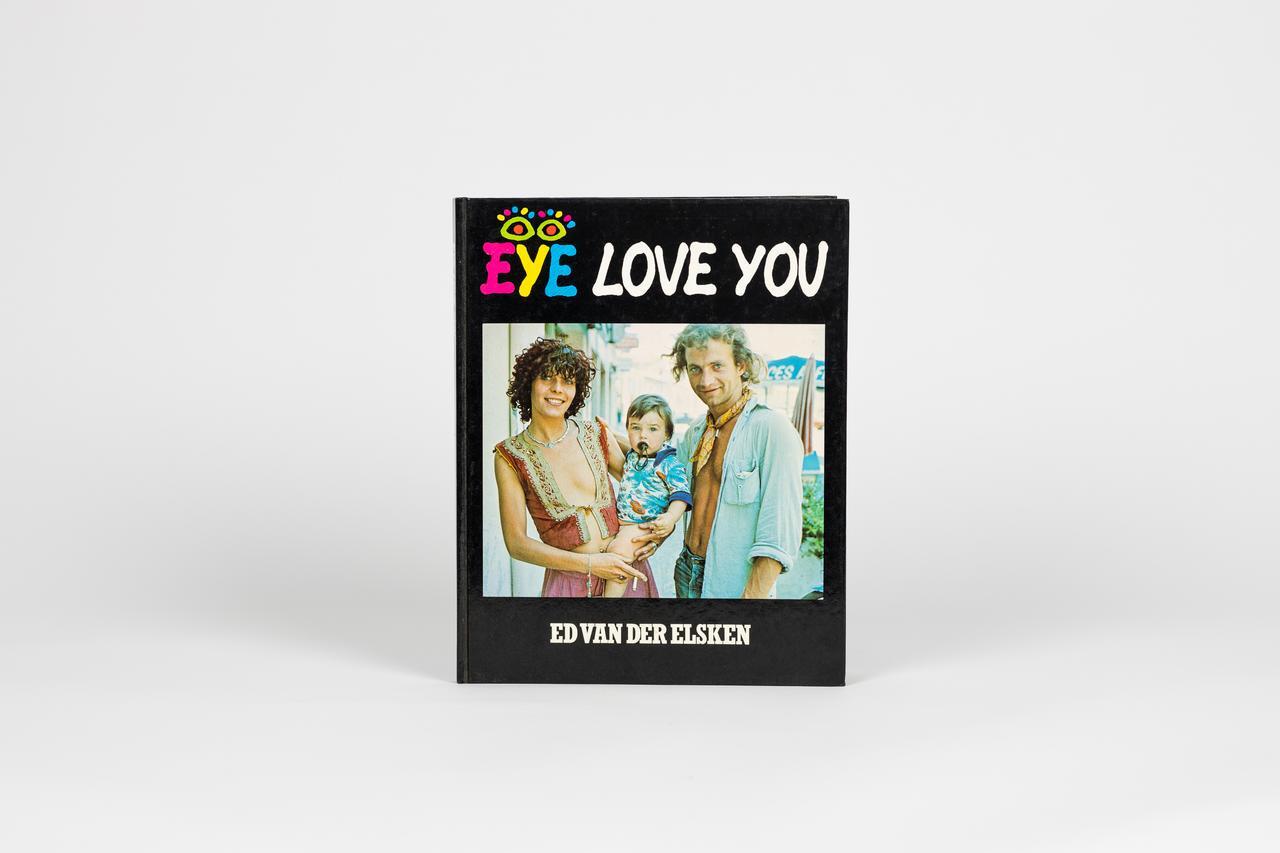

Gio Ponti. L'arte si innamora dell'industria. is a single Italian language hardcover monograph by Gio Ponti, edited by Ugo La Pietra, published in 1995 (second edition) with 406 black-and-white and colour illustrations across 406 pages, measuring 29 cm by 23 cm.

Description from the seller

Gio Ponti. Art falls in love with industry. Edited by Ugo La Pietra. Rizzoli, 1995 (second edition). Black and white and color illustrations. In excellent condition - minimal signs of use on the dust jacket.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Biography

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Ugo La Pietra (Bussi sul Tirino, 1938) is an Italian artist, architect, designer, filmmaker, editor, musician, comic artist, and professor.

Biography

Born in Bussi sul Tirino (Pescara) in 1938, originally from Arpino (Frosinone), he lives and works in Milan, where he graduated in Architecture from the Politecnico in 1964.

An architect by training, since 1960 he has defined himself as a researcher in the system of communication and visual arts, operating simultaneously in the realms of art and design. An tireless experimenter, he has traversed various currents (from Sign painting to conceptual art, from Narrative Art to artist cinema) and used multiple media, conducting research that has materialized in the theory of the 'Disruptive System' – an autonomous expression within Radical Design – and in important sociological themes such as 'The Telematic House' (MoMA in New York, 1972 – Fiera di Milano, 1983), 'Relationship between Real Space and Virtual Space' (Triennale di Milano 1979, 1992), 'The Neo-Eclectic House' (Abitare il tempo, 1990), 'Beach Culture' (Cultural Center Cattolica, 1985/95). He has communicated his work through many exhibitions in Italy and abroad, and in various shows at the Triennale di Milano, Venice Biennale, Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon, FRAC Museum in Orléans, Ceramics Museum of Faenza, Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca, Mudima Foundation in Milan, MA*GA Museum in Gallarate. He has always critically supported the humanistic, meaningful, and territorial component of art and design through works and objects, as well as through theoretical, educational, and editorial activities.

Public collections in Italy

Triennale Design Museum, Milan; Museo della Permanente, Milan; Fondazione Cineteca Italiana, Milan; Museo del Novecento, Milan; Gallerie d’Italia - Collezione Intesa SanPaolo, Milan; Fondazione Ragghianti, Lucca; Fondazione Umberto Mastroianni, Arpino (FR); Fondazione Orestiadi, Gibellina (PA); MIC Museo Internazionale della Ceramica, Faenza (RA); Museo Hoffmann, Caltagirone (CT); Museo Fondazione Rocco Guglielmo, Catanzaro; Museo Palazzo Ducale, Tagliacozzo (AQ); Fondazione PLART, Naples; Museo MAAM Fondazione Aldo Morelato, Cerea (VR); MAGA Museo Arte Gallarate (VA); Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Reggio Calabria; MORE (Museum of Refused and Unrealized Art Projects), Museo Arte Contemporanea di Lissone.

Gio Ponti. Art falls in love with industry. Edited by Ugo La Pietra. Rizzoli, 1995 (second edition). Black and white and color illustrations. In excellent condition - minimal signs of use on the dust jacket.

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio, (Milan, November 18, 1891 – Milan, September 16, 1979), was an Italian architect and designer among the most important of the post-war period.

Biography

Italians are born to build. Building is a characteristic of their race, a shape of their mind, a vocation and commitment of their destiny, an expression of their existence, the supreme and immortal sign of their history.

Gio Ponti, Architectural Vocation of Italians, 1940

Son of Enrico Ponti and Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti graduated in architecture from the then Royal Higher Technical Institute (the future Politecnico di Milano) in 1921, after suspending his studies during his participation in the First World War. In the same year, he married the noble Giulia Vimercati, from an ancient Brianzola family, with whom he had four children (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia, and Giulio).

Twenty and thirty years old

Casa Marmont in Milan, 1934

The Montecatini Palace in Milan, 1938

Initially, in 1921, he opened a studio with architects Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), before collaborating with engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). In 1923, he participated in the First Biennale of Decorative Arts held at the ISIA in Monza and was subsequently involved in organizing various Triennials, both in Monza and Milan.

In the twenties, he started his career as a designer in the ceramic industry with Richard-Ginori, reworking the company's overall industrial design strategy; with his ceramics, he won the 'Grand Prix' at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. During those years, his production was more influenced by classical themes reinterpreted in a Deco style, aligning more closely with the Novecento movement, an exponent of rationalism. Also in those same years, he began his editorial activity: in 1928, he founded the magazine Domus, which he directed until his death, except for the period from 1941 to 1948 when he was the director of Stile. Along with Casabella, Domus would represent the center of the cultural debate on Italian architecture and design in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coffee service 'Barbara' designed by Ponti for Richard Ginori in 1930.

Ponti's activities in the 1930s extended to organizing the V Milan Triennale (1933) and creating sets and costumes for La Scala Theatre. He participated in the Industrial Design Association (ADI) and was among the supporters of the Golden Compass award, promoted by La Rinascente department stores. Among other honors, he received numerous national and international awards, eventually becoming a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1936, a position he held until 1961. In 1934, the Italian Academy awarded him the Mussolini Prize for the arts.

In 1937, he commissioned Giuseppe Cesetti to create a large ceramic floor, exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, in a hall that also featured works by Gino Severini and Massimo Campigli.

The 1940s and 1950s

In 1941, during World War II, Ponti founded the regime's architecture and design magazine STILE. In the magazine, which clearly supported the Rome-Berlin axis, Ponti did not hesitate to include comments in his editorials such as 'In the post-war period, Italy will have enormous tasks... in the relations with its exemplary ally, Germany,' and 'our great allies [Nazi Germany] give us an example of tenacious, serious, organized, and orderly application' (from Stile, August 1941, p. 3). Stile lasted only a few years and closed after the Anglo-American invasion of Italy and the defeat of the Italo-German Axis. In 1948, Ponti reopened the magazine Domus, where he remained as editor until his death.

In 1951, he joined the studio along with Fornaroli, architect Alberto Rosselli. In 1952, he established the Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli studio with architect Alberto Rosselli. This marked the beginning of the most intense and fruitful period of activity in both architecture and design, abandoning frequent links to the neoclassical past and focusing on more innovative ideas.

the sixties and seventies

Between 1966 and 1968, he collaborated with the ceramic manufacturing company Ceramica Franco Pozzi of Gallarate [without a source].

The Communication Studies and Archive Center of Parma houses a collection dedicated to Gio Ponti, consisting of 16,512 sketches and drawings, 73 models and maquettes. The Ponti archive was donated by the architect's heirs (donors Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) in 1982. This collection, whose design material documents the works created by the Milanese designer from the twenties to the seventies, is public and accessible.

Gio Ponti died in Milan in 1979: he is buried at the Milan Monumental Cemetery. His name has earned him a place in the cemetery's memorial register.

Stile

Gio Ponti designed many objects across a wide range of fields, from theatrical sets, lamps, chairs, and kitchen objects to interiors of transatlantic ships. Initially, in the art of ceramics, his designs reflected the Viennese Secession and argued that traditional decoration and modern art were not incompatible. His approach of reconnecting with and utilizing the values of the past found supporters in the fascist regime, which was inclined to safeguard the 'Italian identity' and recover the ideals of 'Romanity,' which was later fully expressed in architecture through the simplified neoclassicism of Piacentini.

La Pavoni coffee machine, designed by Ponti in 1948.

In 1950, Ponti began working on the design of 'fitted walls', or entire prefabricated walls that allowed for the fulfillment of various needs by integrating appliances and equipment that had previously been autonomous into a single system. We also remember Ponti for the design of the 'Superleggera' seat in 1955 (produced by Cassina), created by modifying an existing object typically handcrafted: the Chiavari chair, improved in materials and performance.

Despite this, Ponti built the School of Mathematics in the University City of Rome in 1934 (one of the first works of Italian Rationalism), and in 1936, the first of the office buildings for Montecatini in Milan. The latter, with strongly personal characteristics, reflects in its architectural details, of refined elegance, the designer's penchant for style.

In the 1950s, Ponti's style became more innovative, and while remaining classical in the second office building for Montecatini (1951), it was fully expressed in his most significant work: the Pirelli Skyscraper in Piazza Duca d'Aosta in Milan (1955-1958). The structure was built around a central framework designed by Nervi (127.1 meters). The building appears as a slender and harmonious glass slab that cuts through the architectural space of the sky, designed with a balanced curtain wall, with its long sides narrowing into almost two vertical lines. Even with its character of 'excellence,' this work rightly belongs to the Modern Movement in Italy.

Ugo La Pietra (Bussi sul Tirino, 1938) is an Italian artist, architect, designer, filmmaker, editor, musician, comic artist, and professor.

Biography

Born in Bussi sul Tirino (Pescara) in 1938, originally from Arpino (Frosinone), he lives and works in Milan, where he graduated in Architecture from the Politecnico in 1964.

An architect by training, since 1960 he has defined himself as a researcher in the system of communication and visual arts, operating simultaneously in the realms of art and design. An tireless experimenter, he has traversed various currents (from Sign painting to conceptual art, from Narrative Art to artist cinema) and used multiple media, conducting research that has materialized in the theory of the 'Disruptive System' – an autonomous expression within Radical Design – and in important sociological themes such as 'The Telematic House' (MoMA in New York, 1972 – Fiera di Milano, 1983), 'Relationship between Real Space and Virtual Space' (Triennale di Milano 1979, 1992), 'The Neo-Eclectic House' (Abitare il tempo, 1990), 'Beach Culture' (Cultural Center Cattolica, 1985/95). He has communicated his work through many exhibitions in Italy and abroad, and in various shows at the Triennale di Milano, Venice Biennale, Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon, FRAC Museum in Orléans, Ceramics Museum of Faenza, Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca, Mudima Foundation in Milan, MA*GA Museum in Gallarate. He has always critically supported the humanistic, meaningful, and territorial component of art and design through works and objects, as well as through theoretical, educational, and editorial activities.

Public collections in Italy

Triennale Design Museum, Milan; Museo della Permanente, Milan; Fondazione Cineteca Italiana, Milan; Museo del Novecento, Milan; Gallerie d’Italia - Collezione Intesa SanPaolo, Milan; Fondazione Ragghianti, Lucca; Fondazione Umberto Mastroianni, Arpino (FR); Fondazione Orestiadi, Gibellina (PA); MIC Museo Internazionale della Ceramica, Faenza (RA); Museo Hoffmann, Caltagirone (CT); Museo Fondazione Rocco Guglielmo, Catanzaro; Museo Palazzo Ducale, Tagliacozzo (AQ); Fondazione PLART, Naples; Museo MAAM Fondazione Aldo Morelato, Cerea (VR); MAGA Museo Arte Gallarate (VA); Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Reggio Calabria; MORE (Museum of Refused and Unrealized Art Projects), Museo Arte Contemporanea di Lissone.