Francesco Petrarca - Codice Queiriano di Brescia - 1470-1995

Add to your favourites to get an alert when the auction starts.

Founded and directed two French book fairs; nearly 20 years of experience in contemporary books.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123418 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

Description from the seller

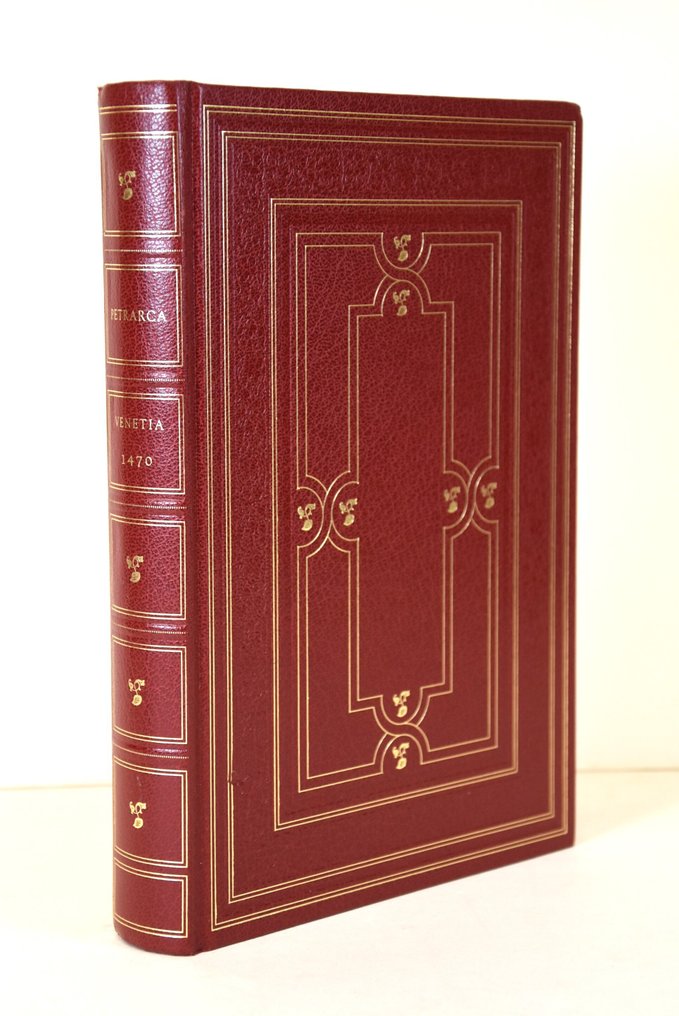

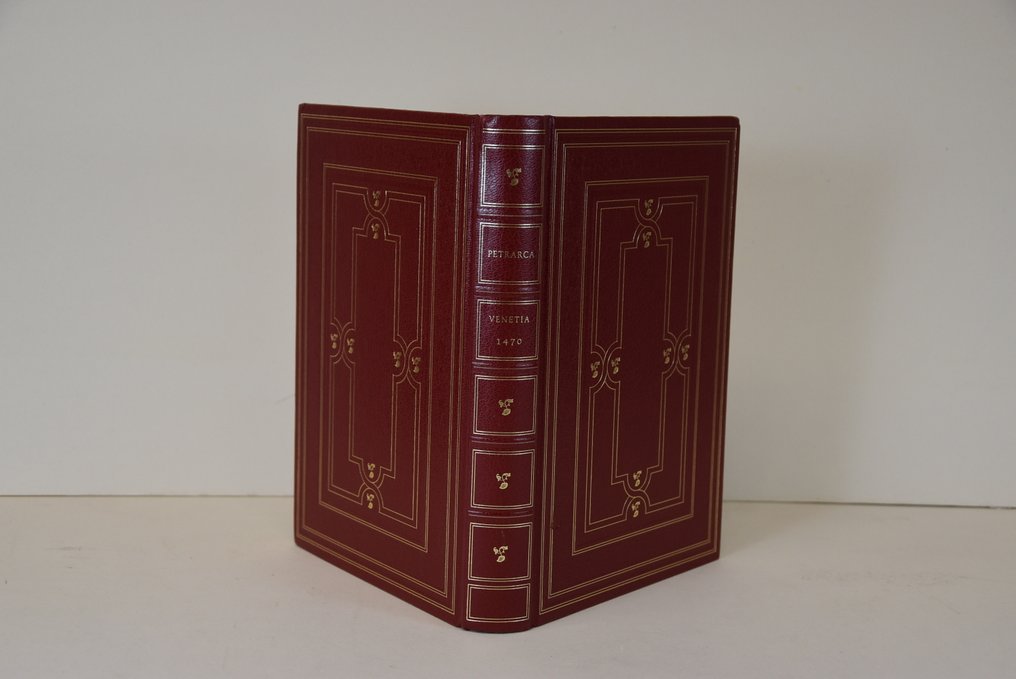

Francesco Petrarca. Reproduction of the Queiriano Codex of Brescia (Inc. G. V. 15). The 51 missing pages are reproduced from the Codex of the Trivulziana Library in Milan. 27 x 19 cm, full leather binding with gold embellishments, 300 pages. In excellent condition. Auction without reserve.

The Querinian Petrarchan incunabulum is an important illuminated incunabulum of the Canzoniere and the Triumphs by Francesco Petrarca, preserved at the Biblioteca Civica Queriniana in Brescia. It is considered a unique piece in the history of Petrarchan editions due to its richness and originality of the illustrative apparatus. The copy is a printed edition from Venice in 1470 by Vindelino da Spira. Each poetic composition (the Rerum vulgarium fragmenta) is accompanied by its own miniatures, an exceptional feature for the time, providing a visual interpretation of the text.

The 'Dilettante Queriniano': The miniaturist, identified by some scholars with Antonio Grifo, is known as the 'Dilettante Queriniano.' His illustrations are inspired by the society and fashion of his time (late 15th century), while also considering Petrarch's verses, and sometimes offer a personal and at times irreverent interpretation of the figure of Laura.

This specimen is therefore a document of great importance for understanding the reception and visual interpretation of Petrarch's work in the fifteenth century.

Giovanni and Vindelino da Spira (Johann and Wendelin von Speyer; Spira, 15th century – Venice, 15th century) were two German typographers, active in the 15th century, famous for introducing movable type printing to Venice.

Biography

After learning the art of movable type printing in Mainz, the two brothers emigrated to Italy. Upon arriving in Venice, they set up the first printing press in the lagoon city.

They immediately started production: the first printed work by the two brothers was Cicero's Epistulae ad familiares. Also in 1469, Giovanni printed the first edition of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia. For this work, the brothers requested and obtained from the Venetian authorities the privilege, essentially the right to print it exclusively within the territory of the Republic, in this case for five years. It was the first time a printer obtained such a right. This was a privilege pro arte, given the absolute novelty of this technology on the Serenissima's soil. A few months later, Giovanni died prematurely, leaving his wife Paola, who was Italian, and two children (a son and a daughter). The privilege expired and was not renewed for other printers in Venice.

In 1470, Vindelino completed the edition of Saint Augustine's De civitate Dei that his brother had begun. Paola married Giovanni from Cologne, a German merchant active in Venice, who financed Vindelino's works until 1477 and then produced books on his own. They printed Latin classics (Plautus, Catullus, Martial, Livy, Tacitus, Sallust) and liturgical works.

Vindelino's most famous incunabulum was Nicolò Malermi's Vulgate Bible (1471), the first printed Italian translation of the Bible.

Francesco Petrarca (Arezzo, July 20, 1304 – Arquà, July 19, 1374) was an Italian writer, poet, philosopher, and philologist, considered the precursor of humanism and one of the foundations of Italian literature, especially thanks to his most famous work, the Canzoniere, which was patronized as a model of stylistic excellence by Pietro Bembo in the early sixteenth century.

A man now freed from the conception of homeland as mother and become a citizen of the world, Petrarch revived Augustinianism in the philosophical realm in opposition to scholasticism and carried out a historical-philological reevaluation of Latin classics. Thus, an advocate for a revival of the studia humanitatis in an anthropocentric sense (no longer in an absolutely theocentric key), Petrarch (who obtained his poetic degree in Rome in 1341) spent his entire life promoting the cultural revival of ancient poetry and philosophy through the imitation of the classics, presenting himself as a champion of virtue and the fight against vices.

The very story of the Canzoniere is more a journey of redemption from the overwhelming love for Laura than a love story, and in this light, the Latin work of the Secretum should also be considered. The themes and the cultural proposal of Petrarchism, besides having founded the humanist cultural movement, initiated the phenomenon of petrarchism, aimed at imitating the styles, lexicon, and poetic genres characteristic of Petrarch's vernacular lyric production.

Biography

The birthplace of Francesco Petrarca in Arezzo, at 28 Borgo dell'Orto Street. The building, dating back to the 15th century, is commonly identified as the poet's birthplace according to tradition and the topographical identification provided by Petrarca himself in the Epistola Posteritati.

Youth and education

The family

Francesco Petrarch was born on July 20, 1304, in Arezzo to ser Petracco, a notary, and Eletta Cangiani (or Canigiani), both from Florence. Petracco, originally from Incisa, belonged to the faction of the white Guelphs and was a friend of Dante Alighieri, who was exiled from Florence in 1302 due to the arrival of Charles of Valois, who apparently entered the Tuscan city as a peacemaker for Pope Boniface VIII but was actually sent to support the black Guelphs against the white Guelphs. The sentence issued on March 10, 1302, by Cante Gabrielli da Gubbio, the podestà of Florence, exiled all the white Guelphs, including ser Petracco, who, in addition to the disgrace of exile, was condemned to have his right hand cut off. After Francesco, a natural son of ser Petracco named Giovanni was born first, about whom Petrarch always remained silent in his writings; he became an Olivetan monk and died in 1384. Later, in 1307, his beloved brother Gherardo was born, who would become a Carthusian monk.

The wandering childhood and the encounter with Dante

Due to his father's exile, young Francesco spent his childhood in various places in Tuscany – first in Arezzo (where the family had initially taken refuge), then in Incisa and Pisa – where his father was accustomed to moving for political and economic reasons. In this city, his father, who had not lost hope of returning to his homeland, had joined the White Guelphs and the Ghibellines in 1311 to welcome Emperor Henry VII. According to what Petrarch himself states in the Familiares, XXI, 15, addressed to his friend Boccaccio, it was in this city that his only and fleeting encounter with his father's friend, Dante, probably took place.

Between France and Italy (1312-1326)

The stay in Carpentras

However, as early as 1312, the family moved to Carpentras, near Avignon (France), where Petracco obtained positions at the papal court thanks to the intercession of Cardinal Niccolò da Prato. Meanwhile, young Francesco studied in Carpentras under the guidance of the scholar Convenevole da Prato (1270/75-1338), a friend of his father who would be remembered by Petrarch with affection in the 'Seniles', XVI, 1. At Convenevole's school, where he studied from 1312 to 1316, he met one of his closest friends, Guido Sette, Archbishop of Genoa from 1358, to whom Petrarch dedicated the 'Seniles', X, 2.

Anonymous, Laura, and the Poet, House of Francesco Petrarca, Arquà Petrarca (province of Padova). The fresco is part of a pictorial cycle created during the sixteenth century while Pietro Paolo Valdezocco was the owner.

Legal studies in Montpellier and Bologna.

The idyll of Carpentras lasted until the autumn of 1316, when Francesco, his brother Gherardo, and their friend Guido Sette were sent by their respective families to study law in Montpellier, a city in Languedoc, also remembered as a place full of peace and joy. Despite this, besides the disinterest and annoyance felt towards jurisprudence, the stay in Montpellier was marred by the first of the various sorrows that Petrarch would face in his life: the death, at only 38 years old, of his mother Eletta in 1318 or 1319. The son, still a teenager, composed the Breve pangerycum defuncte matris (later revised in the epistle metrica 1, 7), in which the virtues of the deceased mother are highlighted, summarized in the Latin word electa.

Shortly after his wife's death, the father decided to change the location for his children's studies, sending them in 1320 to the much more prestigious Bologna, once again accompanied by Guido Sette and a tutor who would oversee the children's daily life. During these years, Petrarch, increasingly impatient with legal studies, became involved with the literary circles of Bologna, becoming a student and friend of the Latinists Giovanni del Virgilio and Bartolino Benincasa, thus beginning his early literary studies and developing that bibliophilia that would accompany him throughout his life. The Bologna years, unlike those spent in Provence, were not peaceful: in 1321, violent riots broke out within the Studium following the decapitation of a student, which led Francesco, Gherardo, and Guido to temporarily return to Avignon. The three returned to Bologna to resume their studies from 1322 to 1325, the year in which Petrarch returned to Avignon to borrow a large sum of money, specifically 200 bolognese lire spent at the Bologna bookseller Bonfigliolo Zambeccari.

The Avignonese period (1326-1341)

The death of the father and service to the Colonna family.

The Palace of the Popes in Avignon, the residence of the Roman pontiffs from 1309 to 1377 during the so-called Avignonese captivity. The Provençal city, at that time a center of Christianity, was a leading cultural and commercial hub, a reality that allowed Petrarch to establish numerous connections with key figures in the political and cultural life of the early 14th century.

In 1326, ser Petracco died, allowing Petrarch to finally leave the law faculty at Bologna and dedicate himself to classical studies, which increasingly fascinated him. To fully devote himself to this pursuit, he needed a source of support that would enable him to earn some income: he found one as a member of the entourage first of Giacomo Colonna, archbishop of Lombez; then of Giacomo's brother, Cardinal Giovanni, from 1330. Joining one of the most influential and powerful families of the Roman aristocracy not only provided Francesco with the security he needed to begin his studies but also allowed him to expand his knowledge within the European cultural and political elite.

Indeed, as a representative of the interests of the Colonna family, Petrarch undertook a long journey across Northern Europe between the spring and summer of 1333, driven by the restless and resurging desire for human and cultural knowledge that marked his entire tumultuous biography: he was in Paris, Ghent, Liège, Aachen, Cologne, and Lyon. The spring/summer of 1330 was particularly significant when, in the city of Lombez, Petrarch met Angelo Tosetti and the Flemish musician and singer Ludwig Van Kempen, the Socrates to whom the collection of letters called Familiares would be dedicated.

Shortly after joining the entourage of Bishop Giovanni, Petrarch took holy orders, becoming a canon in order to obtain the benefits associated with the ecclesiastical institution he was invested in. Despite his status as a member of the clergy (it is documented that from 1330 Petrarch was in the condition of a cleric), he nonetheless fathered children with unknown women, among whom the most notable in the poet's subsequent life are Giovanni (born in 1337) and Francesca (born in 1343).

Portrait of Laura, in a drawing preserved at the Medicea Laurenziana Library[27].

The meeting with Laura

According to what he states in the Secretum, Petrarch first met Laura in the church of Santa Chiara in Avignon on April 6, 1327 (which fell on a Monday. Easter was on April 12, and Good Friday on April 10 that year), the woman (domina) who would be the love of his life and who would be immortalized in the Canzoniere. The figure of Laura has elicited a wide range of opinions from literary critics: some identify her with Laura de Noves, married to de Sade (who died in 1348 due to the plague, like the Petrarchan Laura), while others tend to see this figure as a senhal hiding the figure of the poetic laurel (a plant that, through etymological play, is associated with the female name), the ultimate ambition of the poet Petrarch.

The philological activity

The discovery of the classics and patristic spirituality.

As mentioned earlier, Petrarch already demonstrated a strong literary sensitivity during his stay in Bologna, professing great admiration for classical antiquity. In addition to meetings with Giovanni del Virgilio and Cino da Pistoia, an important factor in the development of the poet's literary sensibility was his father himself, a fervent admirer of Cicero and Latin literature. Cino da Pistoia is also considered, from a stylistic point of view, the father figure alongside Petrarch's vernacular poetry's Stilnovismo. Indeed, Ser Petracco, as Petrarch recounts in the 'Seniles,' XVI, 1, gifted his son a manuscript containing Virgil's works and Cicero's Rhetoric, and in 1325, a codex of Isidore of Seville's 'Etymologiae' and one containing the letters of Saint Paul.

In that same year, demonstrating his ever-growing passion for Patristics, young Francesco purchased a codex of Augustine of Hippo's De civitate Dei and, around 1333, met and began to frequent the Augustinian Dionigi of Borgo San Sepolcro, a learned Augustinian monk and theology professor at the Sorbonne. He gifted young Petrarch a pocket-sized codex of the Confessiones, a reading that further increased our protagonist's passion for Augustinian patristic spirituality. After his father's death and having entered the service of the Colonna family, Petrarch threw himself wholeheartedly into the search for new classics, starting to examine the codices of the Vatican Apostolic Library (where he discovered Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia). During his journey to Northern Europe in 1333, Petrarch discovered and copied the codex of Cicero's Pro Archia poeta and the apocryphal Ad equites romanos, preserved in the Capitular Library of Liège.

The dawn of humanistic philology

Beyond the explorator dimension, Petrarch began to develop, between the twenties and thirties, the foundations for the birth of the modern philological method, based on the collatio method, on the analysis of variants (and therefore on the manuscript tradition of the classics, purging them of the errors of the monk scribes with their emendatio or completing missing parts through conjecture). Based on these methodological premises, Petrarch worked on reconstructing, on one hand, the Ab Urbe condita of the Latin historian Titus Livius; on the other hand, the composition of the great codex containing the works of Virgil, which, due to its current location, is called the Ambrosian Virgil.

From Rome to Valchiusa: Africa and the De viris illustribus

Marie Alexandre Valentin Sellier, The Farandola of Petrarch, oil on canvas, 1900. In the background, the Castle of Noves can be seen, located in Valchiusa, the pleasant place where Petrarch spent much of his life until 1351, the year he left Provence for Italy.

While pursuing these philological projects, Petrarch began a correspondence with Pope Benedict XII (1334-1342) (Epistolae metricae I, 2 and 5), in which he urged the new pontiff to return to Rome, and continued his service with Cardinal Giovanni Colonna, thanks to whom he was able to undertake a journey to Rome at the request of Giacomo Colonna, who wished to have him with him. Arriving there at the end of January 1337, in the Eternal City, Petrarch was able to see firsthand the monuments and ancient glories of the former capital of the Roman Empire, and he was left in awe. Returning to Provence in the summer of 1337, Petrarch bought a house in Valchiusa, a secluded location in the Sorgue valley, in an attempt to escape the frenetic activity of Avignon, an environment he gradually began to detest as a symbol of the moral corruption into which the Papacy had fallen. Valchiusa (which during the poet's absences was entrusted to the steward Raymond Monet of Chermont) was also the place where Petrarch could focus on his literary work and host a small circle of chosen friends (including the Bishop of Cavaillon, Philippe de Cabassolle), with whom he spent days engaged in cultured dialogue and spirituality.

Around the same time, while explaining to Giacomo Colonna the life led at Valchiusa during his first year there, Petrarch sketches one of those mannered self-portraits that would become a common motif in his correspondence: countryside walks, chosen friendships, intense readings, with no ambition other than peaceful living (Epist. I 6, 156-237).

(Pacca, pp. 34-35)

In this secluded period, Petrarch, confident in his philological-literary experience, began composing the two works that would become symbols of the classical Renaissance: Africa and De viris illustribus. The first, an epic poem modeled after Virgilian footsteps, narrates the Roman military campaign of the Second Punic War, focusing on the figures of Scipio Africanus, starting from Cicero's Somnium Scipionis. The second, on the other hand, is a medallion of 36 lives of illustrious men, inspired by the models of Livy and Florus. The choice to compose one work in verse and the other in prose, echoing the great models of antiquity in their respective literary genres and aimed at recovering not only the stylistic form but also the spiritual essence of the ancients, soon spread Petrarch's name beyond Provençal borders, reaching Italy.

Between Italy and Provence (1341-1353)

Giusto di Gand, Francesco Petrarca, painting, 15th century, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino. The laurel wreath with which Petrarch was crowned revitalized the myth of the poet laureate, a figure that would become a public institution in countries such as the United Kingdom.

The poetic coronation

The name of Petrarch, as an exceptionally cultured man and great scholar, was spread thanks to the influence of the Colonna family and the Augustinian Dionigi. While the former had influence within ecclesiastical circles and related institutions (such as European universities, among which the Sorbonne stood out), Father Dionigi made the name of the Aretine known at the court of King Robert of Naples, to whom he was called due to his erudition.

Petrarch, taking advantage of the network of acquaintances and patrons he had, thought of obtaining official recognition for his innovative literary activity in favor of antiquity, thus sponsoring his poetic coronation. In fact, in Familiares, II, 4, Petrarch confided to his Augustinian father his hope of receiving the help of the Angevin sovereign to realize this dream of his, praising him in the process.

Meanwhile, on September 1, 1340, through his chancellor Roberto de' Bardi, the Sorbonne sent our side an offer of a poetic coronation in Paris; a proposal that, on the same day's afternoon, received a similar one from the Senate of Rome. On Giovanni Colonna's advice, Petrarch, who wished to be crowned in the ancient capital of the Roman Empire, accepted the second offer, then accepting King Roberto's invitation to be examined by him in Naples before arriving in Rome for the long-awaited coronation.

The preparation phases for the fateful meeting with the Angevin ruler lasted from October 1340 to the early days of 1341. On February 16, Petrarch, accompanied by the lord of Parma, Azzo da Correggio, set out for Naples with the aim of obtaining the approval of the learned Angevin sovereign. Arriving in the Neapolitan city at the end of February, he was examined for three days by King Robert, who, after recognizing his culture and poetic preparation, consented to his coronation as poet in the Capitol by the hand of Senator Orso dell'Anguillara. As further confirmation of the poet's value, the sovereign wished to lend him his most precious cloak to wear during the coronation ceremony. While we know both the content of Petrarch's speech (the Collatio laureationis) and the certification of his degree by the Roman Senate (the Privilegium lauree domini Francisci Petrarche, which also granted him authority to teach and Roman citizenship), the exact date of the coronation remains uncertain. According to Petrarch and Boccaccio's accounts, the coronation took place sometime between April 8 and April 17. Petrarch, a poet laureate, thus truly follows in the footsteps of Latin poets, aspiring, with the unfinished Africa, to become the new Virgil. The poem effectively concludes at the ninth book, with the poet Ennius prophetically outlining the future of Latin poetry, which finds its culmination in Petrarch himself.

The years 1341-1348

Federico Faruffini, Cola di Rienzo contemplates the ruins of Rome, oil on canvas, 1855, private collection, Pavia. Petrarch shared with Cola the political program of restoration, only to reproach him later when he accepted the political impositions of the Avignon Curia, intimidated by his demagogic politics[58].

The years following the poetic coronation, between 1341 and 1348, were marked by a perpetual state of moral unrest, caused both by traumatic events in private life and by an inexorable disgust towards the Avignonese corruption. Immediately after the poetic coronation, while Petrarch was staying in Parma, he learned of the premature passing of his friend Giacomo Colonna (which occurred in September 1341), a news that deeply disturbed him. The subsequent years offered no comfort to the laureate poet: on one hand, the deaths of Dionigi (March 31, 1342) and then King Roberto (January 19, 1343) heightened his despair; on the other hand, his brother Gherardo's decision to leave worldly life and become a monk at the Certosa di Montrieux prompted Petrarch to reflect on the fleeting nature of the world.

In the autumn of 1342, while Petrarch was staying in Avignon, he met the future tribune Cola di Rienzo, who had arrived in Provence as an ambassador of the democratic regime established in Rome. They shared the need to restore Rome's former political grandeur, which, as the capital of ancient Rome and the seat of the papacy, rightfully belonged to it. That same year, he also met Barlaam of Seminara in Avignon, from whom he sought to learn Greek. Petrarch worked to have him appointed to the diocese of Gerace by Pope Clement VI on October 2 of the same year. In 1346, Petrarch was appointed canon of the Chapter of the cathedral of Parma, and in 1348, he was appointed archdeacon. Cola's political downfall in 1347, especially favored by the Colonna family, was the decisive push for Petrarch to abandon his former protectors: it was indeed in that year that he officially left the entourage of Cardinal Giovanni.

Alongside these private experiences, the path of the intellectual Petrarch was instead marked by a very important discovery. In 1345, after taking refuge in Verona following the siege of Parma and the disgrace of his friend Azzo da Correggio (December 1344), Petrarch discovered in the chapter library the Ciceroian epistles to Brutus, Atticus, and Quintus Frater, which had been unknown until then. The significance of this discovery lay in the epistolary model they conveyed: the remote colloquies with friends, the use of the familiar 'tu' instead of the formal 'voi' typical of medieval epistolography, and finally, the fluid and hypotactic style inspired the Aretine to also compose collections of letters modeled on Cicero and Seneca, leading to the creation of the Familiares first, and the Seniles later. This period also includes the Rerum memorandarum libri (left unfinished), the beginning of De otio religioso and De vita solitaria between 1346 and 1347, which were revised in subsequent years. Also in Verona, Petrarch had the opportunity to meet Pietro Alighieri, Dante's son, with whom he maintained cordial relations.

The Black Death (1348-1349)

Life, as they say, slipped through our hands: our hopes were buried with our friends. 1348 was the year that made us miserable and alone.

(Familiar Things, Preface, To Socrates [Ludwig van Kempen], translated by G. Fracassetti, 1, p. 239)

After breaking free from the Colonna, Petrarch began to seek new patrons for protection. Therefore, having left Avignon with his son Giovanni (whose education was entrusted to the Parmenian scholar and grammarian Moggio Moggi), he arrived in Verona on January 25, 1348, where his friend Azzo da Correggio had taken refuge after being expelled from his domains, and then reached Parma in March, where he established connections with the new ruler of the city, Luchino Visconti of Milan. However, it was during this period that the terrible Black Death began to spread across Europe, a disease that caused the death of many of Petrarch’s friends: the Florentines Sennuccio del Bene, Bruno Casini, and Franceschino degli Albizzi; Cardinal Giovanni Colonna and his father, Stefano the Old; and that of his beloved Laura, whose death he only learned about on May 19 (the event occurred on April 8).

Despite the spread of the contagion and the psychological distress he fell into due to the death of many of his friends, Petrarch continued his journeys, in perpetual search of a protector. He found one in Jacopo II da Carrara, his supporter who in 1349 appointed him as a canon of the cathedral of Padua. The lord of Padua thus intended to keep the poet in the city, who, besides the comfortable house, obtained an annual income of 200 gold ducats from the canonry, but for several years Petrarch only used this residence occasionally. Indeed, constantly driven by the desire to travel, in 1349 he was in Mantua, Ferrara, and Venice, where he met the doge Andrea Dandolo.

Boccaccio (on the left) and Petrarca (on the right) in two engravings by Raffaello Morghen (1758-1833) from 1822. Boccaccio would be one of Petrarca's main interlocutors between 1350 and 1374, shaping, through this partnership, the birth of humanism.

The meeting with Giovanni Boccaccio and his Florentine friends (1350)

The same topic in detail: Giovanni Boccaccio § Boccaccio and Petrarch.

In 1350, he made the decision to go to Rome to gain indulgence for the Jubilee Year. During the journey, he agreed to the requests of his Florentine admirers and decided to meet with them. The occasion was of fundamental importance not so much for Petrarch, but for Giovanni Boccaccio, who would become his main interlocutor during the last twenty years of his life. The novellist, under his guidance, began a slow and progressive conversion towards a more humanistic mindset and approach to literature, often collaborating with his revered teacher on broad cultural projects. Among these, we recall the rediscovery of ancient Greek and the discovery of ancient classical codices.

The last stay in Provence (1351-1353)

Between 1350 and 1351, Petrarch primarily resided in Padua, at Francesco I da Carrara's court. There, in addition to advancing the literary projects of the Familiares and the spiritual works begun before 1348, he also received a visit from Giovanni Boccaccio (March 1351) as an ambassador of the Florentine Commune to accept a teaching position at the new Studium in Florence. Shortly after, Petrarch was urged to return to Avignon following a meeting with Cardinals Eli de Talleyrand and Guy de Boulogne, who conveyed Pope Clement VI's desire to appoint him as apostolic secretary. Despite the enticing offer from the pope, Petrarch's longstanding disdain for Avignon and conflicts with the papal court circles (the pope's doctors and, after Clement's death, the antipathy of the new pope Innocent VI) led him to leave Avignon for Valchiusa, where he made the final decision to settle in Italy.

The Italian period (1353-1374)

In Milan: the figure of the humanist intellectual

Commemorative plaque of Petrarch's Milanese stay located at the beginning of Via Lanzone in Milan, in front of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio.

Petrarch began his journey to his homeland in Italy in April 1353, accepting the hospitable offer of Giovanni Visconti, archbishop and lord of the city, to reside in Milan. Despite criticisms from his Florentine friends (including a resentful remark from Boccaccio), who reproached him for choosing to serve the fierce enemy of Florence, Petrarch collaborated on missions and embassies (to Paris and Venice; the meeting with Emperor Charles IV in Mantua and Prague) in support of the ambitious Visconti politics.

Regarding the choice to reside in Milan rather than Florence, one must remember Petrarch's inherently cosmopolitan spirit. Having grown restless and distant from his homeland, Petrarch no longer felt the medieval attachment to his native land but evaluated invitations based on economic and political convenience. It was indeed better to have the protection of a powerful and wealthy lord like Giovanni Visconti first, and after his death in 1354, his successor Galeazzo II, who would be pleased to have a renowned intellectual like Petrarch at court. Despite this questionable choice in the eyes of his Florentine friends, the relationship between the praeceptor and his disciples was repaired: the resumption of the epistolary relationship between Petrarch and Boccaccio first, and later Boccaccio's visit to Milan to Petrarch's house near Sant'Ambrogio in 1359, are proof of the restored harmony.

Despite diplomatic duties, in the Lombard capital, Petrarch matured and completed that process of intellectual and spiritual growth that began a few years earlier, transitioning from erudite and philological research to the production of philosophical literature rooted on one side in dissatisfaction with contemporary culture, and on the other in the need for a body of work that could guide humanity towards ethical-moral principles filtered through Augustinian neoplatonism and Christian-influenced Stoicism. With this inner conviction, Petrarch continued the writings he had begun during the period of the plague: the Secretum and the De otio religioso; the composition of works aimed at establishing in posterity the image of a virtuous man whose principles are practiced in daily life (the collections of Familiares and, from 1361, the beginning of the Seniles); Latin poetic collections (Epistolae Metricae) and vernacular ones (the Triumphi and the Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta, also known as the Canzoniere). During his stay in Milan, Petrarch only started a new work, the dialogue titled De remediis utriusque fortune, which addresses moral issues concerning money, politics, social relations, and all that pertains to daily life.

The Venetian stay (1362-1367)

Epigraph dictated by Petrarch for his nephew's tomb, Pavia, Civic Museums.

In June 1361, to escape the plague, Petrarch left Milan for Padua, a city from which he fled again in 1362 for the same reason. Despite fleeing Milan, his relations with Galeazzo II Visconti remained very good, so much so that he spent the summer of 1369 at the Visconti castle in Pavia during diplomatic negotiations. In Pavia, he buried his two-year-old nephew, the son of his daughter Francesca, in the church of San Zeno, and composed an epitaph still preserved in the Civic Museums. In 1362, Petrarch then went to Venice, where his dear friend Donato degli Albanzani was located, and where the Republic granted him use of the Palazzo Molin delle due Torri (on the Riva degli Schiavoni) in exchange for the promise of a donation upon his death of his library, which was then certainly the largest private library in Europe: this is the first evidence of a 'bibliotheca publica' project.

Memorial stone of Petrarch in Venice on the Riva degli Schiavoni

The Venetian house was very loved by the poet, who indirectly mentions it in Seniles, IV, 4, when he describes, to the recipient Pietro da Bologna, his daily habits (the letter is dated around 1364/65). He resided there permanently until 1368 (except for some periods in Pavia and Padua) and hosted Giovanni Boccaccio and Leonzio Pilato. During his Venetian stay, spent in the company of his closest friends, Francesca, his natural daughter who married the Milanese Francescuolo da Brossano in 1361, Petrarch decided to entrust the copyist Giovanni Malpaghini with the neat transcription of the Familiares and the Canzoniere. The tranquility of those years was disturbed in 1367 by a clumsy and violent attack on his culture, work, and person by four Averroist philosophers who accused him of ignorance. This episode prompted the writing of the treatise De sui ipsius et multorum ignorantia, in which Petrarch defends his own 'ignorance' in the Aristotelian field in favor of neoplatonic-Christian philosophy, which focuses more on human nature than the former, which aimed to investigate nature based on the dogmas of the philosopher from Stagira. Disappointed by the indifference of the Venetians to the accusations against him, Petrarch decided to leave the lagoon city and thus cancel his donation of his library to the Serenissima.

The Padovan epilogue and death (1367-1374)

Petrarch's house in Arquà Petrarca, a location situated on the Euganean Hills near Padua, where the aging poet spent the last years of his life. Petrarch discusses this residence in the 'Seniles', XV, 5.

Petrarch, after a few short trips, accepted the invitation of his friend and admirer Francesco I da Carrara to settle in Padua in the spring of 1368. The canonical house of Francesco Petrarch, which was assigned to the poet following his appointment to the canonicate, is still visible today at Via Dietro Duomo 26/28 in Padua. The Lord of Padua also donated, in 1369, a house located in the area of Arquà, a quiet town on the Euganean Hills, where he could live. However, the condition of the house was quite rundown, and it took several months before the final move to the new residence could take place, which happened in March 1370. The life of the elderly Petrarch, who was joined by his daughter Francesca's family in 1371, mainly alternated between stays in his beloved house in Arquà and the one near the Duomo of Padua, often enlivened by visits from old friends and admirers, as well as new acquaintances in the Venetian city, including Lombardo della Seta, who from 1367 had replaced Giovanni Malpaghini as the copyist and secretary of the laureate poet. During those years, Petrarch only traveled from Padua once, in October 1373, when he was in Venice as a peacemaker for the treaty between the Venetians and Francesco da Carrara. For the rest of the time, he dedicated himself to revising his works, especially the Canzoniere, an activity he continued until the last days of his life.

Struck by a syncope, he died in Arquà during the night between July 18 and 19, 1374, exactly on the eve of his 70th birthday and, according to legend, while examining a text by Virgil, as hoped for in a letter to Boccaccio. The friar of the Order of the Hermits of Saint Augustine, Bonaventura Badoer Peraga, was chosen to deliver the funeral oration at the funeral, which took place on July 24 in the church of Santa Maria Assunta in the presence of Francesco da Carrara and many other lay and ecclesiastical figures.

Francesco Petrarca. Reproduction of the Queiriano Codex of Brescia (Inc. G. V. 15). The 51 missing pages are reproduced from the Codex of the Trivulziana Library in Milan. 27 x 19 cm, full leather binding with gold embellishments, 300 pages. In excellent condition. Auction without reserve.

The Querinian Petrarchan incunabulum is an important illuminated incunabulum of the Canzoniere and the Triumphs by Francesco Petrarca, preserved at the Biblioteca Civica Queriniana in Brescia. It is considered a unique piece in the history of Petrarchan editions due to its richness and originality of the illustrative apparatus. The copy is a printed edition from Venice in 1470 by Vindelino da Spira. Each poetic composition (the Rerum vulgarium fragmenta) is accompanied by its own miniatures, an exceptional feature for the time, providing a visual interpretation of the text.

The 'Dilettante Queriniano': The miniaturist, identified by some scholars with Antonio Grifo, is known as the 'Dilettante Queriniano.' His illustrations are inspired by the society and fashion of his time (late 15th century), while also considering Petrarch's verses, and sometimes offer a personal and at times irreverent interpretation of the figure of Laura.

This specimen is therefore a document of great importance for understanding the reception and visual interpretation of Petrarch's work in the fifteenth century.

Giovanni and Vindelino da Spira (Johann and Wendelin von Speyer; Spira, 15th century – Venice, 15th century) were two German typographers, active in the 15th century, famous for introducing movable type printing to Venice.

Biography

After learning the art of movable type printing in Mainz, the two brothers emigrated to Italy. Upon arriving in Venice, they set up the first printing press in the lagoon city.

They immediately started production: the first printed work by the two brothers was Cicero's Epistulae ad familiares. Also in 1469, Giovanni printed the first edition of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia. For this work, the brothers requested and obtained from the Venetian authorities the privilege, essentially the right to print it exclusively within the territory of the Republic, in this case for five years. It was the first time a printer obtained such a right. This was a privilege pro arte, given the absolute novelty of this technology on the Serenissima's soil. A few months later, Giovanni died prematurely, leaving his wife Paola, who was Italian, and two children (a son and a daughter). The privilege expired and was not renewed for other printers in Venice.

In 1470, Vindelino completed the edition of Saint Augustine's De civitate Dei that his brother had begun. Paola married Giovanni from Cologne, a German merchant active in Venice, who financed Vindelino's works until 1477 and then produced books on his own. They printed Latin classics (Plautus, Catullus, Martial, Livy, Tacitus, Sallust) and liturgical works.

Vindelino's most famous incunabulum was Nicolò Malermi's Vulgate Bible (1471), the first printed Italian translation of the Bible.

Francesco Petrarca (Arezzo, July 20, 1304 – Arquà, July 19, 1374) was an Italian writer, poet, philosopher, and philologist, considered the precursor of humanism and one of the foundations of Italian literature, especially thanks to his most famous work, the Canzoniere, which was patronized as a model of stylistic excellence by Pietro Bembo in the early sixteenth century.

A man now freed from the conception of homeland as mother and become a citizen of the world, Petrarch revived Augustinianism in the philosophical realm in opposition to scholasticism and carried out a historical-philological reevaluation of Latin classics. Thus, an advocate for a revival of the studia humanitatis in an anthropocentric sense (no longer in an absolutely theocentric key), Petrarch (who obtained his poetic degree in Rome in 1341) spent his entire life promoting the cultural revival of ancient poetry and philosophy through the imitation of the classics, presenting himself as a champion of virtue and the fight against vices.

The very story of the Canzoniere is more a journey of redemption from the overwhelming love for Laura than a love story, and in this light, the Latin work of the Secretum should also be considered. The themes and the cultural proposal of Petrarchism, besides having founded the humanist cultural movement, initiated the phenomenon of petrarchism, aimed at imitating the styles, lexicon, and poetic genres characteristic of Petrarch's vernacular lyric production.

Biography

The birthplace of Francesco Petrarca in Arezzo, at 28 Borgo dell'Orto Street. The building, dating back to the 15th century, is commonly identified as the poet's birthplace according to tradition and the topographical identification provided by Petrarca himself in the Epistola Posteritati.

Youth and education

The family

Francesco Petrarch was born on July 20, 1304, in Arezzo to ser Petracco, a notary, and Eletta Cangiani (or Canigiani), both from Florence. Petracco, originally from Incisa, belonged to the faction of the white Guelphs and was a friend of Dante Alighieri, who was exiled from Florence in 1302 due to the arrival of Charles of Valois, who apparently entered the Tuscan city as a peacemaker for Pope Boniface VIII but was actually sent to support the black Guelphs against the white Guelphs. The sentence issued on March 10, 1302, by Cante Gabrielli da Gubbio, the podestà of Florence, exiled all the white Guelphs, including ser Petracco, who, in addition to the disgrace of exile, was condemned to have his right hand cut off. After Francesco, a natural son of ser Petracco named Giovanni was born first, about whom Petrarch always remained silent in his writings; he became an Olivetan monk and died in 1384. Later, in 1307, his beloved brother Gherardo was born, who would become a Carthusian monk.

The wandering childhood and the encounter with Dante

Due to his father's exile, young Francesco spent his childhood in various places in Tuscany – first in Arezzo (where the family had initially taken refuge), then in Incisa and Pisa – where his father was accustomed to moving for political and economic reasons. In this city, his father, who had not lost hope of returning to his homeland, had joined the White Guelphs and the Ghibellines in 1311 to welcome Emperor Henry VII. According to what Petrarch himself states in the Familiares, XXI, 15, addressed to his friend Boccaccio, it was in this city that his only and fleeting encounter with his father's friend, Dante, probably took place.

Between France and Italy (1312-1326)

The stay in Carpentras

However, as early as 1312, the family moved to Carpentras, near Avignon (France), where Petracco obtained positions at the papal court thanks to the intercession of Cardinal Niccolò da Prato. Meanwhile, young Francesco studied in Carpentras under the guidance of the scholar Convenevole da Prato (1270/75-1338), a friend of his father who would be remembered by Petrarch with affection in the 'Seniles', XVI, 1. At Convenevole's school, where he studied from 1312 to 1316, he met one of his closest friends, Guido Sette, Archbishop of Genoa from 1358, to whom Petrarch dedicated the 'Seniles', X, 2.

Anonymous, Laura, and the Poet, House of Francesco Petrarca, Arquà Petrarca (province of Padova). The fresco is part of a pictorial cycle created during the sixteenth century while Pietro Paolo Valdezocco was the owner.

Legal studies in Montpellier and Bologna.

The idyll of Carpentras lasted until the autumn of 1316, when Francesco, his brother Gherardo, and their friend Guido Sette were sent by their respective families to study law in Montpellier, a city in Languedoc, also remembered as a place full of peace and joy. Despite this, besides the disinterest and annoyance felt towards jurisprudence, the stay in Montpellier was marred by the first of the various sorrows that Petrarch would face in his life: the death, at only 38 years old, of his mother Eletta in 1318 or 1319. The son, still a teenager, composed the Breve pangerycum defuncte matris (later revised in the epistle metrica 1, 7), in which the virtues of the deceased mother are highlighted, summarized in the Latin word electa.

Shortly after his wife's death, the father decided to change the location for his children's studies, sending them in 1320 to the much more prestigious Bologna, once again accompanied by Guido Sette and a tutor who would oversee the children's daily life. During these years, Petrarch, increasingly impatient with legal studies, became involved with the literary circles of Bologna, becoming a student and friend of the Latinists Giovanni del Virgilio and Bartolino Benincasa, thus beginning his early literary studies and developing that bibliophilia that would accompany him throughout his life. The Bologna years, unlike those spent in Provence, were not peaceful: in 1321, violent riots broke out within the Studium following the decapitation of a student, which led Francesco, Gherardo, and Guido to temporarily return to Avignon. The three returned to Bologna to resume their studies from 1322 to 1325, the year in which Petrarch returned to Avignon to borrow a large sum of money, specifically 200 bolognese lire spent at the Bologna bookseller Bonfigliolo Zambeccari.

The Avignonese period (1326-1341)

The death of the father and service to the Colonna family.

The Palace of the Popes in Avignon, the residence of the Roman pontiffs from 1309 to 1377 during the so-called Avignonese captivity. The Provençal city, at that time a center of Christianity, was a leading cultural and commercial hub, a reality that allowed Petrarch to establish numerous connections with key figures in the political and cultural life of the early 14th century.

In 1326, ser Petracco died, allowing Petrarch to finally leave the law faculty at Bologna and dedicate himself to classical studies, which increasingly fascinated him. To fully devote himself to this pursuit, he needed a source of support that would enable him to earn some income: he found one as a member of the entourage first of Giacomo Colonna, archbishop of Lombez; then of Giacomo's brother, Cardinal Giovanni, from 1330. Joining one of the most influential and powerful families of the Roman aristocracy not only provided Francesco with the security he needed to begin his studies but also allowed him to expand his knowledge within the European cultural and political elite.

Indeed, as a representative of the interests of the Colonna family, Petrarch undertook a long journey across Northern Europe between the spring and summer of 1333, driven by the restless and resurging desire for human and cultural knowledge that marked his entire tumultuous biography: he was in Paris, Ghent, Liège, Aachen, Cologne, and Lyon. The spring/summer of 1330 was particularly significant when, in the city of Lombez, Petrarch met Angelo Tosetti and the Flemish musician and singer Ludwig Van Kempen, the Socrates to whom the collection of letters called Familiares would be dedicated.

Shortly after joining the entourage of Bishop Giovanni, Petrarch took holy orders, becoming a canon in order to obtain the benefits associated with the ecclesiastical institution he was invested in. Despite his status as a member of the clergy (it is documented that from 1330 Petrarch was in the condition of a cleric), he nonetheless fathered children with unknown women, among whom the most notable in the poet's subsequent life are Giovanni (born in 1337) and Francesca (born in 1343).

Portrait of Laura, in a drawing preserved at the Medicea Laurenziana Library[27].

The meeting with Laura

According to what he states in the Secretum, Petrarch first met Laura in the church of Santa Chiara in Avignon on April 6, 1327 (which fell on a Monday. Easter was on April 12, and Good Friday on April 10 that year), the woman (domina) who would be the love of his life and who would be immortalized in the Canzoniere. The figure of Laura has elicited a wide range of opinions from literary critics: some identify her with Laura de Noves, married to de Sade (who died in 1348 due to the plague, like the Petrarchan Laura), while others tend to see this figure as a senhal hiding the figure of the poetic laurel (a plant that, through etymological play, is associated with the female name), the ultimate ambition of the poet Petrarch.

The philological activity

The discovery of the classics and patristic spirituality.

As mentioned earlier, Petrarch already demonstrated a strong literary sensitivity during his stay in Bologna, professing great admiration for classical antiquity. In addition to meetings with Giovanni del Virgilio and Cino da Pistoia, an important factor in the development of the poet's literary sensibility was his father himself, a fervent admirer of Cicero and Latin literature. Cino da Pistoia is also considered, from a stylistic point of view, the father figure alongside Petrarch's vernacular poetry's Stilnovismo. Indeed, Ser Petracco, as Petrarch recounts in the 'Seniles,' XVI, 1, gifted his son a manuscript containing Virgil's works and Cicero's Rhetoric, and in 1325, a codex of Isidore of Seville's 'Etymologiae' and one containing the letters of Saint Paul.

In that same year, demonstrating his ever-growing passion for Patristics, young Francesco purchased a codex of Augustine of Hippo's De civitate Dei and, around 1333, met and began to frequent the Augustinian Dionigi of Borgo San Sepolcro, a learned Augustinian monk and theology professor at the Sorbonne. He gifted young Petrarch a pocket-sized codex of the Confessiones, a reading that further increased our protagonist's passion for Augustinian patristic spirituality. After his father's death and having entered the service of the Colonna family, Petrarch threw himself wholeheartedly into the search for new classics, starting to examine the codices of the Vatican Apostolic Library (where he discovered Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia). During his journey to Northern Europe in 1333, Petrarch discovered and copied the codex of Cicero's Pro Archia poeta and the apocryphal Ad equites romanos, preserved in the Capitular Library of Liège.

The dawn of humanistic philology

Beyond the explorator dimension, Petrarch began to develop, between the twenties and thirties, the foundations for the birth of the modern philological method, based on the collatio method, on the analysis of variants (and therefore on the manuscript tradition of the classics, purging them of the errors of the monk scribes with their emendatio or completing missing parts through conjecture). Based on these methodological premises, Petrarch worked on reconstructing, on one hand, the Ab Urbe condita of the Latin historian Titus Livius; on the other hand, the composition of the great codex containing the works of Virgil, which, due to its current location, is called the Ambrosian Virgil.

From Rome to Valchiusa: Africa and the De viris illustribus

Marie Alexandre Valentin Sellier, The Farandola of Petrarch, oil on canvas, 1900. In the background, the Castle of Noves can be seen, located in Valchiusa, the pleasant place where Petrarch spent much of his life until 1351, the year he left Provence for Italy.

While pursuing these philological projects, Petrarch began a correspondence with Pope Benedict XII (1334-1342) (Epistolae metricae I, 2 and 5), in which he urged the new pontiff to return to Rome, and continued his service with Cardinal Giovanni Colonna, thanks to whom he was able to undertake a journey to Rome at the request of Giacomo Colonna, who wished to have him with him. Arriving there at the end of January 1337, in the Eternal City, Petrarch was able to see firsthand the monuments and ancient glories of the former capital of the Roman Empire, and he was left in awe. Returning to Provence in the summer of 1337, Petrarch bought a house in Valchiusa, a secluded location in the Sorgue valley, in an attempt to escape the frenetic activity of Avignon, an environment he gradually began to detest as a symbol of the moral corruption into which the Papacy had fallen. Valchiusa (which during the poet's absences was entrusted to the steward Raymond Monet of Chermont) was also the place where Petrarch could focus on his literary work and host a small circle of chosen friends (including the Bishop of Cavaillon, Philippe de Cabassolle), with whom he spent days engaged in cultured dialogue and spirituality.

Around the same time, while explaining to Giacomo Colonna the life led at Valchiusa during his first year there, Petrarch sketches one of those mannered self-portraits that would become a common motif in his correspondence: countryside walks, chosen friendships, intense readings, with no ambition other than peaceful living (Epist. I 6, 156-237).

(Pacca, pp. 34-35)

In this secluded period, Petrarch, confident in his philological-literary experience, began composing the two works that would become symbols of the classical Renaissance: Africa and De viris illustribus. The first, an epic poem modeled after Virgilian footsteps, narrates the Roman military campaign of the Second Punic War, focusing on the figures of Scipio Africanus, starting from Cicero's Somnium Scipionis. The second, on the other hand, is a medallion of 36 lives of illustrious men, inspired by the models of Livy and Florus. The choice to compose one work in verse and the other in prose, echoing the great models of antiquity in their respective literary genres and aimed at recovering not only the stylistic form but also the spiritual essence of the ancients, soon spread Petrarch's name beyond Provençal borders, reaching Italy.

Between Italy and Provence (1341-1353)

Giusto di Gand, Francesco Petrarca, painting, 15th century, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino. The laurel wreath with which Petrarch was crowned revitalized the myth of the poet laureate, a figure that would become a public institution in countries such as the United Kingdom.

The poetic coronation

The name of Petrarch, as an exceptionally cultured man and great scholar, was spread thanks to the influence of the Colonna family and the Augustinian Dionigi. While the former had influence within ecclesiastical circles and related institutions (such as European universities, among which the Sorbonne stood out), Father Dionigi made the name of the Aretine known at the court of King Robert of Naples, to whom he was called due to his erudition.

Petrarch, taking advantage of the network of acquaintances and patrons he had, thought of obtaining official recognition for his innovative literary activity in favor of antiquity, thus sponsoring his poetic coronation. In fact, in Familiares, II, 4, Petrarch confided to his Augustinian father his hope of receiving the help of the Angevin sovereign to realize this dream of his, praising him in the process.

Meanwhile, on September 1, 1340, through his chancellor Roberto de' Bardi, the Sorbonne sent our side an offer of a poetic coronation in Paris; a proposal that, on the same day's afternoon, received a similar one from the Senate of Rome. On Giovanni Colonna's advice, Petrarch, who wished to be crowned in the ancient capital of the Roman Empire, accepted the second offer, then accepting King Roberto's invitation to be examined by him in Naples before arriving in Rome for the long-awaited coronation.

The preparation phases for the fateful meeting with the Angevin ruler lasted from October 1340 to the early days of 1341. On February 16, Petrarch, accompanied by the lord of Parma, Azzo da Correggio, set out for Naples with the aim of obtaining the approval of the learned Angevin sovereign. Arriving in the Neapolitan city at the end of February, he was examined for three days by King Robert, who, after recognizing his culture and poetic preparation, consented to his coronation as poet in the Capitol by the hand of Senator Orso dell'Anguillara. As further confirmation of the poet's value, the sovereign wished to lend him his most precious cloak to wear during the coronation ceremony. While we know both the content of Petrarch's speech (the Collatio laureationis) and the certification of his degree by the Roman Senate (the Privilegium lauree domini Francisci Petrarche, which also granted him authority to teach and Roman citizenship), the exact date of the coronation remains uncertain. According to Petrarch and Boccaccio's accounts, the coronation took place sometime between April 8 and April 17. Petrarch, a poet laureate, thus truly follows in the footsteps of Latin poets, aspiring, with the unfinished Africa, to become the new Virgil. The poem effectively concludes at the ninth book, with the poet Ennius prophetically outlining the future of Latin poetry, which finds its culmination in Petrarch himself.

The years 1341-1348

Federico Faruffini, Cola di Rienzo contemplates the ruins of Rome, oil on canvas, 1855, private collection, Pavia. Petrarch shared with Cola the political program of restoration, only to reproach him later when he accepted the political impositions of the Avignon Curia, intimidated by his demagogic politics[58].

The years following the poetic coronation, between 1341 and 1348, were marked by a perpetual state of moral unrest, caused both by traumatic events in private life and by an inexorable disgust towards the Avignonese corruption. Immediately after the poetic coronation, while Petrarch was staying in Parma, he learned of the premature passing of his friend Giacomo Colonna (which occurred in September 1341), a news that deeply disturbed him. The subsequent years offered no comfort to the laureate poet: on one hand, the deaths of Dionigi (March 31, 1342) and then King Roberto (January 19, 1343) heightened his despair; on the other hand, his brother Gherardo's decision to leave worldly life and become a monk at the Certosa di Montrieux prompted Petrarch to reflect on the fleeting nature of the world.

In the autumn of 1342, while Petrarch was staying in Avignon, he met the future tribune Cola di Rienzo, who had arrived in Provence as an ambassador of the democratic regime established in Rome. They shared the need to restore Rome's former political grandeur, which, as the capital of ancient Rome and the seat of the papacy, rightfully belonged to it. That same year, he also met Barlaam of Seminara in Avignon, from whom he sought to learn Greek. Petrarch worked to have him appointed to the diocese of Gerace by Pope Clement VI on October 2 of the same year. In 1346, Petrarch was appointed canon of the Chapter of the cathedral of Parma, and in 1348, he was appointed archdeacon. Cola's political downfall in 1347, especially favored by the Colonna family, was the decisive push for Petrarch to abandon his former protectors: it was indeed in that year that he officially left the entourage of Cardinal Giovanni.

Alongside these private experiences, the path of the intellectual Petrarch was instead marked by a very important discovery. In 1345, after taking refuge in Verona following the siege of Parma and the disgrace of his friend Azzo da Correggio (December 1344), Petrarch discovered in the chapter library the Ciceroian epistles to Brutus, Atticus, and Quintus Frater, which had been unknown until then. The significance of this discovery lay in the epistolary model they conveyed: the remote colloquies with friends, the use of the familiar 'tu' instead of the formal 'voi' typical of medieval epistolography, and finally, the fluid and hypotactic style inspired the Aretine to also compose collections of letters modeled on Cicero and Seneca, leading to the creation of the Familiares first, and the Seniles later. This period also includes the Rerum memorandarum libri (left unfinished), the beginning of De otio religioso and De vita solitaria between 1346 and 1347, which were revised in subsequent years. Also in Verona, Petrarch had the opportunity to meet Pietro Alighieri, Dante's son, with whom he maintained cordial relations.

The Black Death (1348-1349)

Life, as they say, slipped through our hands: our hopes were buried with our friends. 1348 was the year that made us miserable and alone.

(Familiar Things, Preface, To Socrates [Ludwig van Kempen], translated by G. Fracassetti, 1, p. 239)

After breaking free from the Colonna, Petrarch began to seek new patrons for protection. Therefore, having left Avignon with his son Giovanni (whose education was entrusted to the Parmenian scholar and grammarian Moggio Moggi), he arrived in Verona on January 25, 1348, where his friend Azzo da Correggio had taken refuge after being expelled from his domains, and then reached Parma in March, where he established connections with the new ruler of the city, Luchino Visconti of Milan. However, it was during this period that the terrible Black Death began to spread across Europe, a disease that caused the death of many of Petrarch’s friends: the Florentines Sennuccio del Bene, Bruno Casini, and Franceschino degli Albizzi; Cardinal Giovanni Colonna and his father, Stefano the Old; and that of his beloved Laura, whose death he only learned about on May 19 (the event occurred on April 8).

Despite the spread of the contagion and the psychological distress he fell into due to the death of many of his friends, Petrarch continued his journeys, in perpetual search of a protector. He found one in Jacopo II da Carrara, his supporter who in 1349 appointed him as a canon of the cathedral of Padua. The lord of Padua thus intended to keep the poet in the city, who, besides the comfortable house, obtained an annual income of 200 gold ducats from the canonry, but for several years Petrarch only used this residence occasionally. Indeed, constantly driven by the desire to travel, in 1349 he was in Mantua, Ferrara, and Venice, where he met the doge Andrea Dandolo.

Boccaccio (on the left) and Petrarca (on the right) in two engravings by Raffaello Morghen (1758-1833) from 1822. Boccaccio would be one of Petrarca's main interlocutors between 1350 and 1374, shaping, through this partnership, the birth of humanism.

The meeting with Giovanni Boccaccio and his Florentine friends (1350)

The same topic in detail: Giovanni Boccaccio § Boccaccio and Petrarch.

In 1350, he made the decision to go to Rome to gain indulgence for the Jubilee Year. During the journey, he agreed to the requests of his Florentine admirers and decided to meet with them. The occasion was of fundamental importance not so much for Petrarch, but for Giovanni Boccaccio, who would become his main interlocutor during the last twenty years of his life. The novellist, under his guidance, began a slow and progressive conversion towards a more humanistic mindset and approach to literature, often collaborating with his revered teacher on broad cultural projects. Among these, we recall the rediscovery of ancient Greek and the discovery of ancient classical codices.

The last stay in Provence (1351-1353)

Between 1350 and 1351, Petrarch primarily resided in Padua, at Francesco I da Carrara's court. There, in addition to advancing the literary projects of the Familiares and the spiritual works begun before 1348, he also received a visit from Giovanni Boccaccio (March 1351) as an ambassador of the Florentine Commune to accept a teaching position at the new Studium in Florence. Shortly after, Petrarch was urged to return to Avignon following a meeting with Cardinals Eli de Talleyrand and Guy de Boulogne, who conveyed Pope Clement VI's desire to appoint him as apostolic secretary. Despite the enticing offer from the pope, Petrarch's longstanding disdain for Avignon and conflicts with the papal court circles (the pope's doctors and, after Clement's death, the antipathy of the new pope Innocent VI) led him to leave Avignon for Valchiusa, where he made the final decision to settle in Italy.

The Italian period (1353-1374)

In Milan: the figure of the humanist intellectual

Commemorative plaque of Petrarch's Milanese stay located at the beginning of Via Lanzone in Milan, in front of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio.

Petrarch began his journey to his homeland in Italy in April 1353, accepting the hospitable offer of Giovanni Visconti, archbishop and lord of the city, to reside in Milan. Despite criticisms from his Florentine friends (including a resentful remark from Boccaccio), who reproached him for choosing to serve the fierce enemy of Florence, Petrarch collaborated on missions and embassies (to Paris and Venice; the meeting with Emperor Charles IV in Mantua and Prague) in support of the ambitious Visconti politics.

Regarding the choice to reside in Milan rather than Florence, one must remember Petrarch's inherently cosmopolitan spirit. Having grown restless and distant from his homeland, Petrarch no longer felt the medieval attachment to his native land but evaluated invitations based on economic and political convenience. It was indeed better to have the protection of a powerful and wealthy lord like Giovanni Visconti first, and after his death in 1354, his successor Galeazzo II, who would be pleased to have a renowned intellectual like Petrarch at court. Despite this questionable choice in the eyes of his Florentine friends, the relationship between the praeceptor and his disciples was repaired: the resumption of the epistolary relationship between Petrarch and Boccaccio first, and later Boccaccio's visit to Milan to Petrarch's house near Sant'Ambrogio in 1359, are proof of the restored harmony.

Despite diplomatic duties, in the Lombard capital, Petrarch matured and completed that process of intellectual and spiritual growth that began a few years earlier, transitioning from erudite and philological research to the production of philosophical literature rooted on one side in dissatisfaction with contemporary culture, and on the other in the need for a body of work that could guide humanity towards ethical-moral principles filtered through Augustinian neoplatonism and Christian-influenced Stoicism. With this inner conviction, Petrarch continued the writings he had begun during the period of the plague: the Secretum and the De otio religioso; the composition of works aimed at establishing in posterity the image of a virtuous man whose principles are practiced in daily life (the collections of Familiares and, from 1361, the beginning of the Seniles); Latin poetic collections (Epistolae Metricae) and vernacular ones (the Triumphi and the Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta, also known as the Canzoniere). During his stay in Milan, Petrarch only started a new work, the dialogue titled De remediis utriusque fortune, which addresses moral issues concerning money, politics, social relations, and all that pertains to daily life.

The Venetian stay (1362-1367)

Epigraph dictated by Petrarch for his nephew's tomb, Pavia, Civic Museums.

In June 1361, to escape the plague, Petrarch left Milan for Padua, a city from which he fled again in 1362 for the same reason. Despite fleeing Milan, his relations with Galeazzo II Visconti remained very good, so much so that he spent the summer of 1369 at the Visconti castle in Pavia during diplomatic negotiations. In Pavia, he buried his two-year-old nephew, the son of his daughter Francesca, in the church of San Zeno, and composed an epitaph still preserved in the Civic Museums. In 1362, Petrarch then went to Venice, where his dear friend Donato degli Albanzani was located, and where the Republic granted him use of the Palazzo Molin delle due Torri (on the Riva degli Schiavoni) in exchange for the promise of a donation upon his death of his library, which was then certainly the largest private library in Europe: this is the first evidence of a 'bibliotheca publica' project.

Memorial stone of Petrarch in Venice on the Riva degli Schiavoni

The Venetian house was very loved by the poet, who indirectly mentions it in Seniles, IV, 4, when he describes, to the recipient Pietro da Bologna, his daily habits (the letter is dated around 1364/65). He resided there permanently until 1368 (except for some periods in Pavia and Padua) and hosted Giovanni Boccaccio and Leonzio Pilato. During his Venetian stay, spent in the company of his closest friends, Francesca, his natural daughter who married the Milanese Francescuolo da Brossano in 1361, Petrarch decided to entrust the copyist Giovanni Malpaghini with the neat transcription of the Familiares and the Canzoniere. The tranquility of those years was disturbed in 1367 by a clumsy and violent attack on his culture, work, and person by four Averroist philosophers who accused him of ignorance. This episode prompted the writing of the treatise De sui ipsius et multorum ignorantia, in which Petrarch defends his own 'ignorance' in the Aristotelian field in favor of neoplatonic-Christian philosophy, which focuses more on human nature than the former, which aimed to investigate nature based on the dogmas of the philosopher from Stagira. Disappointed by the indifference of the Venetians to the accusations against him, Petrarch decided to leave the lagoon city and thus cancel his donation of his library to the Serenissima.

The Padovan epilogue and death (1367-1374)

Petrarch's house in Arquà Petrarca, a location situated on the Euganean Hills near Padua, where the aging poet spent the last years of his life. Petrarch discusses this residence in the 'Seniles', XV, 5.

Petrarch, after a few short trips, accepted the invitation of his friend and admirer Francesco I da Carrara to settle in Padua in the spring of 1368. The canonical house of Francesco Petrarch, which was assigned to the poet following his appointment to the canonicate, is still visible today at Via Dietro Duomo 26/28 in Padua. The Lord of Padua also donated, in 1369, a house located in the area of Arquà, a quiet town on the Euganean Hills, where he could live. However, the condition of the house was quite rundown, and it took several months before the final move to the new residence could take place, which happened in March 1370. The life of the elderly Petrarch, who was joined by his daughter Francesca's family in 1371, mainly alternated between stays in his beloved house in Arquà and the one near the Duomo of Padua, often enlivened by visits from old friends and admirers, as well as new acquaintances in the Venetian city, including Lombardo della Seta, who from 1367 had replaced Giovanni Malpaghini as the copyist and secretary of the laureate poet. During those years, Petrarch only traveled from Padua once, in October 1373, when he was in Venice as a peacemaker for the treaty between the Venetians and Francesco da Carrara. For the rest of the time, he dedicated himself to revising his works, especially the Canzoniere, an activity he continued until the last days of his life.

Struck by a syncope, he died in Arquà during the night between July 18 and 19, 1374, exactly on the eve of his 70th birthday and, according to legend, while examining a text by Virgil, as hoped for in a letter to Boccaccio. The friar of the Order of the Hermits of Saint Augustine, Bonaventura Badoer Peraga, was chosen to deliver the funeral oration at the funeral, which took place on July 24 in the church of Santa Maria Assunta in the presence of Francesco da Carrara and many other lay and ecclesiastical figures.