Ustad'Osman - Livre des Augures - 1582-2007

Add to your favourites to get an alert when the auction starts.

Founded and directed two French book fairs; nearly 20 years of experience in contemporary books.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123418 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

Description from the seller

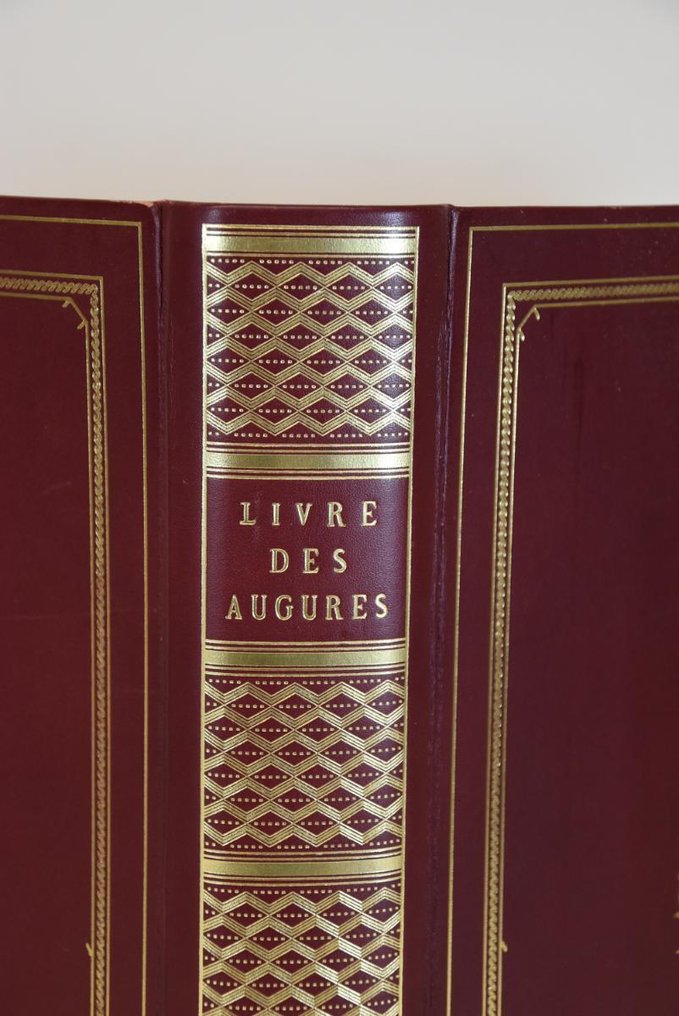

Book of Auguries. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Facsimile edition by M. Moleiro, 2007. 31 x 21 cm, red leather Turkish binding with gold decorations, leather case, 286 pages. 71 full-page miniatures with gold ornaments. Edition of 987 numbered copies (our no. 35). In excellent condition. The critical volume is missing. Auction without reserve price.

Written at the request of Sultan Murad III, The Book of Happiness contains a description of the twelve zodiac signs accompanied by splendid miniatures: a series of illustrations depicting various human situations depending on planetary conjunctions, a table of physiognomic concordances, another for the correct interpretation of dreams, as well as a vast chapter on divination, where anyone can learn to understand their destiny. All the illustrations seem to have been created in a single workshop under the direction of the renowned master Ustad 'Osman, undoubtedly the author of the initial series dedicated to the zodiac signs. Sultan Murad III was completely absorbed in the intense political, cultural, and sentimental life of his harem. He had 103 children, of whom only 47 survived. Yet, Murad III, whose admiration for illuminated manuscripts surpassed that of any other sultan, commissioned this treatise on happiness for his favorite daughter, named Fatima.

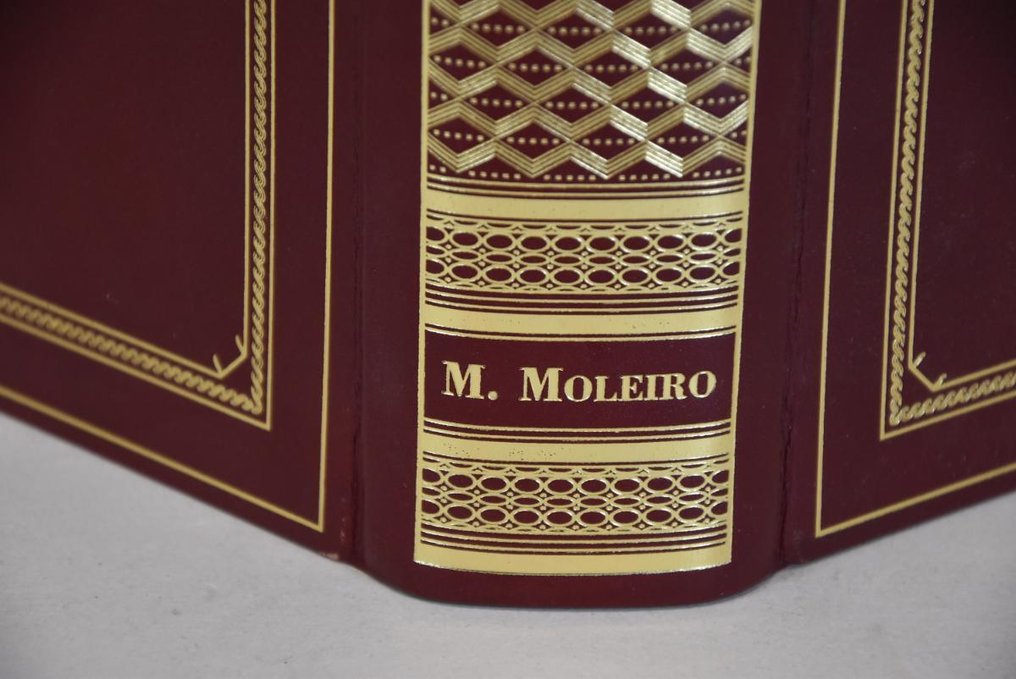

M. Moleiro Editor is a Spanish publishing house specializing in high-quality reproductions of codices, maps, and illuminated manuscripts, almost original in limited editions. Founded in Barcelona in 1991, the company has reproduced numerous illustrated works of art from history, primarily medieval.

In 1976, still a student, Manuel Moleiro founded the publishing house Ebrisa and published a series of art, science, and cartography books, participating in various projects in collaboration with Times Books, Encyclopaedia Britannica, MacMillan, Edita, L'Imprimerie Nationale, and Franco Maria Ricci.

Subsequently, in 1991, he founded a new company under his name as a brand. Since then, he has specialized in the exact reproduction of various bibliographic jewelry from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, thanks to permissions obtained from major libraries and museums worldwide such as La Bibliothèque nationale de France, the British Library, the Morgan Library & Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Russian National Library, the Huntington Library, and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Each reproduction is always accompanied by an explanatory volume created by academic specialists in the field.

Activities

M. Moleiro Editor's publications are so accurate that they are very difficult to distinguish from the original masterpieces. For this reason, the publisher decided to call his works, which go beyond simple copies, 'quasi-originals.' All manuscripts produced by M. Moleiro are first and unique editions made in 987 copies, and they are always accompanied by a notarized authenticity document.

In 2001, the British newspaper The Times considered this editorial work as 'the art of perfection' and a year later, editor Allegra Stratton wrote that 'The Pope was sleeping with a nearly original by Moleiro next to his bed'.

Over time, other personalities known worldwide joined Pope John Paul II, including former Presidents of the United States Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and George Bush, Nobel laureate José Saramago, the President of Portugal Aníbal Cavaco Silva, and King Juan Carlos of Spain.

Masterpieces by M. Moleiro Editor

Among the most important works reproduced by M. Moleiro are the following:

Beatus of Liébana, Beatus of San Pedro de Cardeña, Beatus of San Andrés de Arroyo, Beatus of Silos, Beatus of Ferdinand I and Donna Sancha, and Beatus of Girona. He also published three volumes of the Bible of Saint Louis, a Bible that plays an important role in the history of universal art [4], containing a total of 4,887 miniatures. Among his masterpieces are also several Books of Hours, such as the Breviary of Isabella the Catholic, the Grandes Heures of Anna of Brittany, the Book of Hours of Joanna I of Castile, the Book of Hours of Henry VIII and Henry IV of France, as well as various medical treatises like the Book of Simple Medicines or the Tacuinum Sanitatis, in addition to major cartographic works such as the Miller Atlas and the Vallard Atlas.

Murad III (Ottoman Turkish: مراد ثالث, Turkish: III. Murat; Magnesia, July 4, 1546 – Istanbul, January 16, 1595) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death.

Biography

Şehzade Murad was born in Manisa on July 4, 1546. He was the fourth-born and the first and only son of the future sultan Selim II (1566-1574) and his favorite Nurbanu Sultan. He had three older sisters, Şah Sultan, Gevherhan Sultan, and Ismihan Sultan, and a younger sister, Fatma Sultan, as well as seven younger half-brothers, five of whom were still alive at the time and whom he had killed immediately upon ascending to the throne, as required by the Law of Fratricide, despite none of them being older than four years.

Upon the death of grandfather Solimano the Magnificent, the father became the new sultan, and Murad became the presumed heir, being sent as governor to Manisa.

Regno

In 1574, upon the death of his father, Murad ascended to the throne and began his reign by strangling his five younger brothers.

However, his authority was undermined by the influences of the harem, particularly by the pressures of his mother and later his favorite wife, Safiye Sultan. During Selim II's reign, the capable and powerful Grand Vizier Mehmet Sokollu worked to ensure the stability of the empire, but he was assassinated in October 1579. Murad III's reign was marked by the first signs of political and economic decline of the Ottoman Empire, as well as wars against the Safavid Empire (Ottoman-Safavid War (1578-1590)) and the Habsburg Empire (the so-called 'Long War').

The Ottoman Empire reached its maximum extent in the Middle East under Murad III.

Murad's reign was a period of financial stress for the state. To keep up with changing military techniques, Ottoman infantry were trained to use firearms, paid directly from the treasury. In 1580, an influx of silver from the New World also caused high inflation and social tensions, especially among the Janissaries and government officials.

Numerous letters were exchanged between Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III. To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin, lead, and ammunition to the Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations with Murad III during the outbreak of war with Spain in 1585. These diplomatic relations continued even under Mehmed III and Safiye Sultan.

Palace life

Following the example of his father Selim II, Murad was the second Ottoman sultan who never participated in military campaigns during his reign, spending all his time in Istanbul and, during the last years of his rule, not even leaving Topkapı Palace. For two consecutive years, he never took part in the Friday procession. Ottoman historian Mustafa Selaniki wrote that whenever Murad planned to go out for the Friday prayer, he would change his mind at the last moment, worried about alleged plots by the Janissaries to dethrone him once he left the palace. For this reason, he spent most of his time in the company of a few people, following a strict routine based on the five daily prayers of the Islamic tradition.

His sedentary lifestyle, combined with his lack of participation in military campaigns, earned him the disapproval of Mustafa Ali and Mustafa Selaniki, the leading Ottoman historians who lived during his reign, whose negative portrayals of Murad also influenced subsequent historians. Both accused him of sexual excesses. Before becoming sultan, Murad was faithful to Safiye Sultan, his Albanian concubine who had given him at least two sons, Mehmed and Mahmud, and at least two daughters, Ayse and Fatma. However, his monogamy was not approved by his mother, who believed Murad needed more sons ready to succeed him in case he died young and his children did not survive childhood. In reality, she was more concerned about Safiye's influence over her son and the Ottoman dynasty, which opposed her. Five or six years after ascending to the throne, Murad was offered two concubines by his sister Ismihan. During attempts to have sexual relations with them, the Sultan proved impotent. Nurbanu Sultan accused Safiye and her followers of causing Murad's impotence through witchcraft. Many of Safiye's servants were tortured by eunuchs to discover the culprit. Court doctors, working under Nurbanu's orders, finally prepared a cure that succeeded, to the point that it was believed he had fathered over a hundred children. Nineteen of these children were later killed by Mehmed III when he himself became Sultan.

It is also widely believed that Murad was influenced not only by his mother and sister but also by Canfeda Hatun, Raziye Hatun, and the poetess Hubbi Hatun.

Murad and the arts

Murad had a great interest in the arts, particularly miniatures and books. He actively supported the Society of Court Miniaturists, which published several volumes including the Siyer-i Nebi, the most important illustrated work on the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Book of Skills, the Book of Festivals, and the Book of Victories. He also owned two large alabaster urns, transported from Pergamon, placed on either side of the nave of the Basilica of Santa Sofia in Constantinople, and a large wax candle covered with tin that he donated to the Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, which is now on display in the monastery museum. In Magnesia, he commissioned Mimar Sinan to build the mosque that bears his name.

Family

It is believed that Murad had Safiye Sultan as his only concubine for about fifteen years. However, Safiye was opposed by Murad's mother, Nurbanu Sultan, and his sister, Ismihan Sultan, who, besides contesting her influence over the Sultan, were concerned about the future of the dynasty, which at that time had only one heir, since only one of Murad and Safiye's sons, Mehmed, who was also childless at the time, had survived. In 1580, Nurbanu and Ismihan managed to persuade Murad to exile Safiye to the Old Palace, accusing her of rendering the sultan impotent with a spell after he had failed or refused to consummate a sexual relationship with two concubines received from his sister. After Safiye's exile, which was only reversed after Nurbanu's death in December 1583, Murad, to dispel the rumors, took a large number of concubines and fathered more than fifty known children, although sources suggest the total number could exceed a hundred.

Consorti

Murad's notes on the consortium:

Safiye Sultan, Haseki Sultan and mother of her successor.

Şemsiruhsar Hatun, mother of Rukiye Sultan. She commissioned Quranic recitations at the Prophet's Mosque in Medina. She died before 1623.

Mihriban Hatun[9]

Şahıhuban Hatun, who built a school in Fatih, where she is buried.

Nazperver Hatun commissioned a mosque in Eyüp.

Fakriye Hatun[9]

Zerefşan Hatun

A concubine who died in childbirth in August 1591, along with her son.

Fifteen pregnant concubines in 1595. By order of Mehmed III, they were sealed in sacks and drowned in the Sea of Marmara.

Concubine seduced and pregnant by Mehmed III when he was a prince. The act was a violation of the harem rules, and the girl was drowned by Nurbanu Sultan to protect her grandson.

After the death of Murad III, many of his concubines who had no children were remarried upon the ascension of Mehmed III, along with those who had never borne children to the sultan, mostly to palace officials such as gatekeepers, cavalry officers (bölük halkı), and sergeants (çavus).

Children

Murad III had at least twenty-seven known children.

Upon his death in 1595, Mehmed III, his eldest son and new sultan, executed the 19 still-living half-brothers and drowned seven pregnant concubines, fulfilling the Law of Fratricide.

The known children of Murad III are:

Mehmed III (Manisa, May 16 or 26, 1566 – Constantinople, December 21 or 22, 1603. Buried in the mausoleum of Mehmed III in the Hagia Sofia mosque) was the son of Safiye Sultan and succeeded his father as Ottoman sultan.

Şehzade Selim (Manisa, 1567 - 25 May 1577) - son of Safiye Sultan, died during childhood.

Şehzade Mahmud (Manisa, 1568 - 1580, or first-born. Buried in the mausoleum of Selim II in the Hagia Sofia mosque) - son of Safiye Sultan.

Şehzade Fülan (Constantinople, June 1582 - Constantinople, June 1582. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Born dead.

Prince Cihangir (Constantinople, February 1585 – Constantinople, August 1585. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Twin of Prince Süleyman.

Prince Süleyman (Constantinople, February 1585 – Constantinople, 1585. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Twin of Prince Cihangir.

Şehzade Abdullah (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Mustafa (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Protected by Canfeda Hatun, who attempted to place him on the throne after Murad's death. Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Abdurrahman (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Bayezid (Constantinople, 1586 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Hasan (Constantinople, 1586 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Cihangir (Constantinople, 1587 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Yakub (Constantinople, 1587 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Ahmed (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, before 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque).

Şehzade Fülan (August 1591, born dead);

Prince Alaeddin (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Davud (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, 28 January 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Alemşah (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Ali (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Hüseyn (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Ishak (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Murad (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Osman (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Yusuf (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Korkud (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Sultan Ömer (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Sultan Selim (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

In addition to these, a European pretender, Alessandro del Montenegro, claimed to be the lost son of Murad III and Safiye Sultan, presenting himself under the name of Şehzade Yahya and claiming the throne for himself. His claims were never proven and appear, to say the least, dubious.

Daughters

At the time of his death, Murad III had at least thirty daughters alive, although only the names of some are known. Nineteen of them died in an epidemic of plague or smallpox in 1598. It is unknown whether and how many daughters he may have had who died before him.

The notable daughters of Mehmed III are.

Hümaşah Sultan (Manisa, 1564? – Constantinople, 1648. Buried in the mausoleum of Murad III in the Hagia Sophia mosque) – daughter of Safiye Sultan. Also called Hüma Sultan. She married Nişar Mustafazade Mehmed Pasha in 1582 and was widowed in 1586. She may have married Serdar Ferhad Pasha in 1592. She remained a widow in 1595. She finally married Nakkaş Hasan Pasha in 1605 (died in 1622).

Ayşe Sultan (Manisa, circa 1565 - Constantinople, 15 May 1605. Buried in the mausoleum of Murad III in the Hagia Sophia mosque) - daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married first Ibrāhīm Pascià, second Yemişçi Hasan Pascià, and third Güzelce Mahmud Pascià.

Fatma Sultan (Manisa, 1573 – Constantinople, 1620. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) – daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married first Halil Pasha, second Cafer Pasha, third Hızır Pasha, and fourth Murad Pasha.

Mihrimah Sultan (Constantinople, 1578/1579? – Constantinople, after 1625; buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) – possible daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married at least three times.

Fahriye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, 1656. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque) - possibly the daughter of Safiye Sultan, born after her mother's return from exile at Palazzo Vecchio in 1584. Also called Fahri Sultan. In 1604, she married Cuhadar Ahmed Pasha, governor of Mosul, and was widowed in 1618. In 1618, she married Sofu Bayram Pasha, governor of Bosnia, and was widowed in 1632. She finally married Deli Dilaver Pasha. She had no known children. She received a stipend of 430 aspers per day. On one occasion, she approached the grand vizir to protest against the Ragusan embassy, which had neglected to offer her gifts as usual and refused to remedy the situation.

Rukiye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) - daughter of Şemsiruhsar Hatun.

Hatice Sultan (Constantinople, 1583 - Constantinople, 1648, buried in the Şehzade Mosque). She married Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Pasha in 1598 and had two sons and a daughter. After becoming widowed, she married Gürşci Mehmed Pasha of Kefe, governor of Bosnia.

Mihriban Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). She married in 1613.

Fethiye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque).

Beyhan Sultan (died in 1648), in 1613 married the vizier Kurşuncuzade Mustafa Pasha.

Sehime Sultan (? - ?), in 1613, married Topal Mehmed Pasha, former Kapucıbaşı.

A daughter married to Davud Pasha.

A daughter married Kücük Mirahur Mehmed Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Mirahur-i Evvel Muslu Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Bostancıbaşı Hasan Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Cığalazade Mehmed Bey in 1613 (son of Scipione Cicala and Safiye Hanimsultan).

Nineteen daughters died of the plague in 1598.

A daughter who died as an infant on July 29, 1585.

Book of Auguries. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Facsimile edition by M. Moleiro, 2007. 31 x 21 cm, red leather Turkish binding with gold decorations, leather case, 286 pages. 71 full-page miniatures with gold ornaments. Edition of 987 numbered copies (our no. 35). In excellent condition. The critical volume is missing. Auction without reserve price.

Written at the request of Sultan Murad III, The Book of Happiness contains a description of the twelve zodiac signs accompanied by splendid miniatures: a series of illustrations depicting various human situations depending on planetary conjunctions, a table of physiognomic concordances, another for the correct interpretation of dreams, as well as a vast chapter on divination, where anyone can learn to understand their destiny. All the illustrations seem to have been created in a single workshop under the direction of the renowned master Ustad 'Osman, undoubtedly the author of the initial series dedicated to the zodiac signs. Sultan Murad III was completely absorbed in the intense political, cultural, and sentimental life of his harem. He had 103 children, of whom only 47 survived. Yet, Murad III, whose admiration for illuminated manuscripts surpassed that of any other sultan, commissioned this treatise on happiness for his favorite daughter, named Fatima.

M. Moleiro Editor is a Spanish publishing house specializing in high-quality reproductions of codices, maps, and illuminated manuscripts, almost original in limited editions. Founded in Barcelona in 1991, the company has reproduced numerous illustrated works of art from history, primarily medieval.

In 1976, still a student, Manuel Moleiro founded the publishing house Ebrisa and published a series of art, science, and cartography books, participating in various projects in collaboration with Times Books, Encyclopaedia Britannica, MacMillan, Edita, L'Imprimerie Nationale, and Franco Maria Ricci.

Subsequently, in 1991, he founded a new company under his name as a brand. Since then, he has specialized in the exact reproduction of various bibliographic jewelry from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, thanks to permissions obtained from major libraries and museums worldwide such as La Bibliothèque nationale de France, the British Library, the Morgan Library & Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Russian National Library, the Huntington Library, and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Each reproduction is always accompanied by an explanatory volume created by academic specialists in the field.

Activities

M. Moleiro Editor's publications are so accurate that they are very difficult to distinguish from the original masterpieces. For this reason, the publisher decided to call his works, which go beyond simple copies, 'quasi-originals.' All manuscripts produced by M. Moleiro are first and unique editions made in 987 copies, and they are always accompanied by a notarized authenticity document.

In 2001, the British newspaper The Times considered this editorial work as 'the art of perfection' and a year later, editor Allegra Stratton wrote that 'The Pope was sleeping with a nearly original by Moleiro next to his bed'.

Over time, other personalities known worldwide joined Pope John Paul II, including former Presidents of the United States Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and George Bush, Nobel laureate José Saramago, the President of Portugal Aníbal Cavaco Silva, and King Juan Carlos of Spain.

Masterpieces by M. Moleiro Editor

Among the most important works reproduced by M. Moleiro are the following:

Beatus of Liébana, Beatus of San Pedro de Cardeña, Beatus of San Andrés de Arroyo, Beatus of Silos, Beatus of Ferdinand I and Donna Sancha, and Beatus of Girona. He also published three volumes of the Bible of Saint Louis, a Bible that plays an important role in the history of universal art [4], containing a total of 4,887 miniatures. Among his masterpieces are also several Books of Hours, such as the Breviary of Isabella the Catholic, the Grandes Heures of Anna of Brittany, the Book of Hours of Joanna I of Castile, the Book of Hours of Henry VIII and Henry IV of France, as well as various medical treatises like the Book of Simple Medicines or the Tacuinum Sanitatis, in addition to major cartographic works such as the Miller Atlas and the Vallard Atlas.

Murad III (Ottoman Turkish: مراد ثالث, Turkish: III. Murat; Magnesia, July 4, 1546 – Istanbul, January 16, 1595) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death.

Biography

Şehzade Murad was born in Manisa on July 4, 1546. He was the fourth-born and the first and only son of the future sultan Selim II (1566-1574) and his favorite Nurbanu Sultan. He had three older sisters, Şah Sultan, Gevherhan Sultan, and Ismihan Sultan, and a younger sister, Fatma Sultan, as well as seven younger half-brothers, five of whom were still alive at the time and whom he had killed immediately upon ascending to the throne, as required by the Law of Fratricide, despite none of them being older than four years.

Upon the death of grandfather Solimano the Magnificent, the father became the new sultan, and Murad became the presumed heir, being sent as governor to Manisa.

Regno

In 1574, upon the death of his father, Murad ascended to the throne and began his reign by strangling his five younger brothers.

However, his authority was undermined by the influences of the harem, particularly by the pressures of his mother and later his favorite wife, Safiye Sultan. During Selim II's reign, the capable and powerful Grand Vizier Mehmet Sokollu worked to ensure the stability of the empire, but he was assassinated in October 1579. Murad III's reign was marked by the first signs of political and economic decline of the Ottoman Empire, as well as wars against the Safavid Empire (Ottoman-Safavid War (1578-1590)) and the Habsburg Empire (the so-called 'Long War').

The Ottoman Empire reached its maximum extent in the Middle East under Murad III.

Murad's reign was a period of financial stress for the state. To keep up with changing military techniques, Ottoman infantry were trained to use firearms, paid directly from the treasury. In 1580, an influx of silver from the New World also caused high inflation and social tensions, especially among the Janissaries and government officials.

Numerous letters were exchanged between Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III. To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin, lead, and ammunition to the Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations with Murad III during the outbreak of war with Spain in 1585. These diplomatic relations continued even under Mehmed III and Safiye Sultan.

Palace life

Following the example of his father Selim II, Murad was the second Ottoman sultan who never participated in military campaigns during his reign, spending all his time in Istanbul and, during the last years of his rule, not even leaving Topkapı Palace. For two consecutive years, he never took part in the Friday procession. Ottoman historian Mustafa Selaniki wrote that whenever Murad planned to go out for the Friday prayer, he would change his mind at the last moment, worried about alleged plots by the Janissaries to dethrone him once he left the palace. For this reason, he spent most of his time in the company of a few people, following a strict routine based on the five daily prayers of the Islamic tradition.

His sedentary lifestyle, combined with his lack of participation in military campaigns, earned him the disapproval of Mustafa Ali and Mustafa Selaniki, the leading Ottoman historians who lived during his reign, whose negative portrayals of Murad also influenced subsequent historians. Both accused him of sexual excesses. Before becoming sultan, Murad was faithful to Safiye Sultan, his Albanian concubine who had given him at least two sons, Mehmed and Mahmud, and at least two daughters, Ayse and Fatma. However, his monogamy was not approved by his mother, who believed Murad needed more sons ready to succeed him in case he died young and his children did not survive childhood. In reality, she was more concerned about Safiye's influence over her son and the Ottoman dynasty, which opposed her. Five or six years after ascending to the throne, Murad was offered two concubines by his sister Ismihan. During attempts to have sexual relations with them, the Sultan proved impotent. Nurbanu Sultan accused Safiye and her followers of causing Murad's impotence through witchcraft. Many of Safiye's servants were tortured by eunuchs to discover the culprit. Court doctors, working under Nurbanu's orders, finally prepared a cure that succeeded, to the point that it was believed he had fathered over a hundred children. Nineteen of these children were later killed by Mehmed III when he himself became Sultan.

It is also widely believed that Murad was influenced not only by his mother and sister but also by Canfeda Hatun, Raziye Hatun, and the poetess Hubbi Hatun.

Murad and the arts

Murad had a great interest in the arts, particularly miniatures and books. He actively supported the Society of Court Miniaturists, which published several volumes including the Siyer-i Nebi, the most important illustrated work on the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Book of Skills, the Book of Festivals, and the Book of Victories. He also owned two large alabaster urns, transported from Pergamon, placed on either side of the nave of the Basilica of Santa Sofia in Constantinople, and a large wax candle covered with tin that he donated to the Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, which is now on display in the monastery museum. In Magnesia, he commissioned Mimar Sinan to build the mosque that bears his name.

Family

It is believed that Murad had Safiye Sultan as his only concubine for about fifteen years. However, Safiye was opposed by Murad's mother, Nurbanu Sultan, and his sister, Ismihan Sultan, who, besides contesting her influence over the Sultan, were concerned about the future of the dynasty, which at that time had only one heir, since only one of Murad and Safiye's sons, Mehmed, who was also childless at the time, had survived. In 1580, Nurbanu and Ismihan managed to persuade Murad to exile Safiye to the Old Palace, accusing her of rendering the sultan impotent with a spell after he had failed or refused to consummate a sexual relationship with two concubines received from his sister. After Safiye's exile, which was only reversed after Nurbanu's death in December 1583, Murad, to dispel the rumors, took a large number of concubines and fathered more than fifty known children, although sources suggest the total number could exceed a hundred.

Consorti

Murad's notes on the consortium:

Safiye Sultan, Haseki Sultan and mother of her successor.

Şemsiruhsar Hatun, mother of Rukiye Sultan. She commissioned Quranic recitations at the Prophet's Mosque in Medina. She died before 1623.

Mihriban Hatun[9]

Şahıhuban Hatun, who built a school in Fatih, where she is buried.

Nazperver Hatun commissioned a mosque in Eyüp.

Fakriye Hatun[9]

Zerefşan Hatun

A concubine who died in childbirth in August 1591, along with her son.

Fifteen pregnant concubines in 1595. By order of Mehmed III, they were sealed in sacks and drowned in the Sea of Marmara.

Concubine seduced and pregnant by Mehmed III when he was a prince. The act was a violation of the harem rules, and the girl was drowned by Nurbanu Sultan to protect her grandson.

After the death of Murad III, many of his concubines who had no children were remarried upon the ascension of Mehmed III, along with those who had never borne children to the sultan, mostly to palace officials such as gatekeepers, cavalry officers (bölük halkı), and sergeants (çavus).

Children

Murad III had at least twenty-seven known children.

Upon his death in 1595, Mehmed III, his eldest son and new sultan, executed the 19 still-living half-brothers and drowned seven pregnant concubines, fulfilling the Law of Fratricide.

The known children of Murad III are:

Mehmed III (Manisa, May 16 or 26, 1566 – Constantinople, December 21 or 22, 1603. Buried in the mausoleum of Mehmed III in the Hagia Sofia mosque) was the son of Safiye Sultan and succeeded his father as Ottoman sultan.

Şehzade Selim (Manisa, 1567 - 25 May 1577) - son of Safiye Sultan, died during childhood.

Şehzade Mahmud (Manisa, 1568 - 1580, or first-born. Buried in the mausoleum of Selim II in the Hagia Sofia mosque) - son of Safiye Sultan.

Şehzade Fülan (Constantinople, June 1582 - Constantinople, June 1582. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Born dead.

Prince Cihangir (Constantinople, February 1585 – Constantinople, August 1585. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Twin of Prince Süleyman.

Prince Süleyman (Constantinople, February 1585 – Constantinople, 1585. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Twin of Prince Cihangir.

Şehzade Abdullah (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Mustafa (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Protected by Canfeda Hatun, who attempted to place him on the throne after Murad's death. Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Abdurrahman (Constantinople, 1585 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Bayezid (Constantinople, 1586 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Hasan (Constantinople, 1586 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Cihangir (Constantinople, 1587 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Yakub (Constantinople, 1587 – Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Ahmed (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, before 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque).

Şehzade Fülan (August 1591, born dead);

Prince Alaeddin (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Davud (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, 28 January 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Alemşah (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Ali (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Hüseyn (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Ishak (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Murad (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Osman (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Şehzade Yusuf (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Prince Korkud (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Sultan Ömer (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

Sultan Selim (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, January 28, 1595. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). Executed by Mehmed III.

In addition to these, a European pretender, Alessandro del Montenegro, claimed to be the lost son of Murad III and Safiye Sultan, presenting himself under the name of Şehzade Yahya and claiming the throne for himself. His claims were never proven and appear, to say the least, dubious.

Daughters

At the time of his death, Murad III had at least thirty daughters alive, although only the names of some are known. Nineteen of them died in an epidemic of plague or smallpox in 1598. It is unknown whether and how many daughters he may have had who died before him.

The notable daughters of Mehmed III are.

Hümaşah Sultan (Manisa, 1564? – Constantinople, 1648. Buried in the mausoleum of Murad III in the Hagia Sophia mosque) – daughter of Safiye Sultan. Also called Hüma Sultan. She married Nişar Mustafazade Mehmed Pasha in 1582 and was widowed in 1586. She may have married Serdar Ferhad Pasha in 1592. She remained a widow in 1595. She finally married Nakkaş Hasan Pasha in 1605 (died in 1622).

Ayşe Sultan (Manisa, circa 1565 - Constantinople, 15 May 1605. Buried in the mausoleum of Murad III in the Hagia Sophia mosque) - daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married first Ibrāhīm Pascià, second Yemişçi Hasan Pascià, and third Güzelce Mahmud Pascià.

Fatma Sultan (Manisa, 1573 – Constantinople, 1620. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) – daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married first Halil Pasha, second Cafer Pasha, third Hızır Pasha, and fourth Murad Pasha.

Mihrimah Sultan (Constantinople, 1578/1579? – Constantinople, after 1625; buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) – possible daughter of Safiye Sultan. She married at least three times.

Fahriye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, 1656. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia mosque) - possibly the daughter of Safiye Sultan, born after her mother's return from exile at Palazzo Vecchio in 1584. Also called Fahri Sultan. In 1604, she married Cuhadar Ahmed Pasha, governor of Mosul, and was widowed in 1618. In 1618, she married Sofu Bayram Pasha, governor of Bosnia, and was widowed in 1632. She finally married Deli Dilaver Pasha. She had no known children. She received a stipend of 430 aspers per day. On one occasion, she approached the grand vizir to protest against the Ragusan embassy, which had neglected to offer her gifts as usual and refused to remedy the situation.

Rukiye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque) - daughter of Şemsiruhsar Hatun.

Hatice Sultan (Constantinople, 1583 - Constantinople, 1648, buried in the Şehzade Mosque). She married Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Pasha in 1598 and had two sons and a daughter. After becoming widowed, she married Gürşci Mehmed Pasha of Kefe, governor of Bosnia.

Mihriban Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque). She married in 1613.

Fethiye Sultan (Constantinople, ? - Constantinople, ?. Buried in Murad III's mausoleum in the Hagia Sofia mosque).

Beyhan Sultan (died in 1648), in 1613 married the vizier Kurşuncuzade Mustafa Pasha.

Sehime Sultan (? - ?), in 1613, married Topal Mehmed Pasha, former Kapucıbaşı.

A daughter married to Davud Pasha.

A daughter married Kücük Mirahur Mehmed Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Mirahur-i Evvel Muslu Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Bostancıbaşı Hasan Agha in 1613.

A daughter married Cığalazade Mehmed Bey in 1613 (son of Scipione Cicala and Safiye Hanimsultan).

Nineteen daughters died of the plague in 1598.

A daughter who died as an infant on July 29, 1585.