P.A. Matthiolo - Erbario Matthiolo - 1564-2021

Founded and directed two French book fairs; nearly 20 years of experience in contemporary books.

Bidder 2037 Bidder 2037 | €320 | |

|---|---|---|

Bidder 0561 Bidder 0561 | €300 | |

Bidder 2037 Bidder 2037 | €290 | |

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123609 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

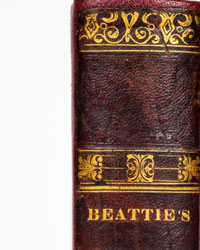

Erbario Matthiolo by P.A. Matthiolo, bound in leather, original Italian, 370 pages, 26.5 x 19.5 cm, edition limited (oldest 1564, latest 2021), in excellent condition.

Description from the seller

Dioscorides of Food and Mattioli. 1564-1584 circa. The British Library, London Ms. 22332. Leather binding with titles and gold embellishments, housed inside a leather box with gold decorations. 370 pages with 168 full-page miniatures. In excellent condition. Edition of 987 numbered copies (our no. 311). The volume on the authors' studies is missing.

The brilliant artist and botanist Gherardo Cibo (1512-1600), great-grandson of Pope Innocent VIII, is the creator of the splendid miniatures that illuminate this extraordinary manuscript. The text is that of Pietro Andrea Mattioli's Discourses (1501-1577), an eminent naturalist and personal physician to Ferdinand II. In the Discourses, the contents of the famous De materia Medica by Dioscorides are commented upon, with the addition of many new plant species, some recently discovered in Tyrol, the East, and America. Unlike those in Dioscorides' treatise, these species were included in the work for their uniqueness and beauty. The manuscript, which would become a precursor of modern botany, was already highly successful in its time. Among the various works Cibo painted based on Mattioli's writings, this is the most beautiful, as evidenced by a letter in which Mattioli himself warmly congratulates Cibo on the outcome of his work. A fundamental work for lovers of medicine, botany, and painting in general, due to the meticulous detail and colors with which not only the different plant species are illustrated but also the vibrant landscapes that serve as their background and often depict their natural habitat.

Food, Gherardo

Born in Genoa in 1512 to Aranino and Bianca Vigeri Della Rovere, a relative of Francesco Maria I, Duke of Urbino, and grandson of Marco Vigeri, Bishop of Senigallia. The paternal family belonged to a branch of the Cibo family descended from Teodorina, daughter of Giovanni Battista Cibo, who became Pope Innocent VIII.

Lady and Gherardo Usodimare of Genoa were the parents of Aranino, born in 1484, who was the custodian of the Camerino fortress and died in Sarzana in 1568, after obtaining the title of Count of the Lateran Palace. From Aranino's marriage, who had received from the Pope the concession to assume and transmit the surname Cibo, and Bianca Vigeri, were born, in addition to C., Marzia, Maddalena, Scipione, and Maria. The two sisters, Marzia and Maddalena, respectively married Count Antonio Maurugi of Tolentino and Domenico Passionei, gonfaloniere of Urbino. From this family, two centuries later, Cardinal Domenico Passionei was born, a renowned bibliophile who made a significant contribution to the collection of the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome. Scipione, born in Genoa in 1531, traveled extensively across Europe and died in Siena in 1597. The youngest sister, Maria, was a nun at the monastery of S. Agata in Arcevia.

After an initial period of residence in his hometown, C. spent his adolescence in Rome, where he arrived following the Duchess of Camerino, Caterina Cibo da Varano, a relative, in 1526 for study purposes and also to pursue an ecclesiastical career. But the sack of Rome forced him to leave immediately from the city invaded by the Landsknecht. C. stayed for a few months in Camerino with Duke Giovanni Maria da Varano. Upon his death in August 1529, he followed Francesco Maria Della Rovere, captain general of the Church's armies, in a series of military campaigns in the Po Valley and Bologna, where he had gone for Charles V's coronation. In Bologna, C. was able to attend Luca Ghini's botany lessons until 1532.

This period was very important for C.'s scientific education, as he learned from Ghini the method of collecting, cataloging, and mounting plants for the creation of an herbarium. It is known that Ghini himself collected dried plants, which he sometimes sent to contemporary botanists like Mattioli; however, his herbarium, like those of his students John Falconer and William Turner, was destroyed.

Even during his Bologna years, C. was able to begin collecting material for his herbarium. However, it was mainly during his travels in subsequent years that he had the opportunity to expand his research scope. In 1532, in fact, his father took him to the court of Charles V, where he was tasked with negotiating the marriage, which later did not take place, between Giulia da Varano, daughter of Caterina Cibo, and Charles of Lannoy, son of the Prince of Sulmona. This two-year journey through the valley of the Adige and the Danube, from Trento to Ingolstadt and Regensburg, in the Upper Palatinate, was a valuable opportunity for C. to conduct botanical research, which he continued even upon returning to Italy.

-ALT

In 1534, he was at Agnano near Lorenzo Cibo, a relative of his, and was able to undertake detailed botanical and mineralogical excursions around Pisa. In 1539, he set out again for Germany, accompanying Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, a learned and generous man who had been his study companion in Bologna. His motivation for this journey was not only the scientific aim of collecting material for his herbarium and engaging with foreign botanists but also the religious purpose of contributing to the fight against Lutheranism. However, it was his deep religiosity that convinced him to leave the armies and return to the peace of his studies. It is also possible that his decision was influenced by the political conflict conducted by the Farnese against the Cibo and Della Rovere families over the possession of Camerino. In fact, the Camerino state, an ancient lordship of the Varano family, had been transferred, by order of Pope Paul III Farnese, to Ottavio, his nephew; faced with the conflicts between his family and that of his powerful protector Alessandro Farnese, he preferred to retreat into scholarly solitude at Rocca Contrada (the present-day Arcevia) in 1540.

He still took some trips, to the Marche, Umbria, and Rome, where he visited in 1553; but he practically spent the rest of his life always in Arcevia, from where he set out for daily excursions in the surroundings and on the Marche Apennines to collect plants and minerals. Not lacking in marked artistic talents, he used to paint the plants he collected with a fine taste for detail; this activity, alongside and as an extension of his naturalistic curiosity, was not merely a pastime, as his paintings and drawings, preserved in Arcevia, are of notable artistic merit, especially the landscapes. Information about his daily activities is known through a Diary that C. kept starting in 1553, of which Celani (1902, pp. 208-11) reports some excerpts (although no news of it is currently available).

A meticulous and precise scholar, C. had the habit of annotating and supplementing the works he read with notes and drawings, such as those by Pliny, Leonhart Fuchs, and Garcia Dall'Orto. Notably, there is an edition of Dioscorides (Venice 1568) by the Sienese botanist Pierandrea Mattioli, a friend of C. and with whom he corresponded through letters, illustrated with miniatures and drawings for Cardinal Della Rovere (today preserved at the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome, shelf mark Ae q II). He also prepared various drawings for the Cardinal of Urbino and other correspondents, including remarkable large zoological plates (also in the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome, MS. 2).

Despite his withdrawn life, which was rather unusual for a scientist, C. was in correspondence with the most experienced botanists of his time, from Ulisse Aldrovandi to Andrea Bacci, from Fuchs to the aforementioned Mattioli. There is no record of his relations with Cesalpino, who was also a student of Ghini (not in Bologna, but in Pisa) and in correspondence with Aldrovandi and Bacci. On the other hand, the organizational criteria of Cesalpino's herbarium differ from those of C., whose herbarium is not systematically arranged but alphabetical, like that of Aldrovandi. This coincidence of method can be attributed both to their common master Ghini and to the close relations between Aldrovandi and Cibo. In a letter from 1576 (published by De Toni, pp. 103-108), Aldrovandi demonstrates that he is familiar with C.'s herbarium and possesses its index; he sends his friend some clarifications about various plants, including Lunaria tonda (which C. had sent him a drawing), and about a fabulous two-headed snake, the amphisbaena. Regarding this curious reptile, C.: had written, according to Aldrovandi (in Serpentum et draconum historiae libri duo, Bononiae 1640 [but 1639], p. 238), a memoir in which he claimed to have seen it. It seems certain, however, that he had sent several valuable pieces to the Aldrovandi natural museum, and that this relationship had both stimulating effects for both parties. Besides the aforementioned memoir, only cited by Aldrovandi, there is no record of other works by C., as such works cannot be considered those of other authors (preserved at the Biblioteca Angelica), which he commented on with medical, botanical, and mineralogical annotations, or the recipes scattered in letters (e.g., one published by Celani, 1902, pp. 222-26). This justifies the silence of contemporary catalogs and botanical works about him.

The attribution to C. of the herbarium preserved at the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome and studied particularly by E. Celani and O. Penzig sparked a lively controversy between Celani on one side and Chiovenda and De Toni on the other during the years 1907-1909, as the latter argued that the author of most of this herbarium was not C., but the Viterbese botanist Francesco Petrollini, also part of the Aldrovandi circle, in fact the master and guide of Aldrovandi in collecting plant specimens. It is not possible to give a definitive answer to the question; what is certain is that the herbarium kept at Angelica is the oldest among those that have come down to us. It consists of five volumes: the first, called "A" by Penzig, is quite damaged and contains three hundred twenty-two unnumbered sheets with four hundred ninety specimens of alpine and subalpine flora, without any systematic criterion (this could be, contrary to Chiovenda's opinion, the herbarium of C. mentioned by Aldrovandi in the above letter); the other four volumes (herbarium "B"), completed before 1551, are altogether made up of nine hundred thirty-eight sheets with one thousand three hundred forty-six specimens, many of the same species. The number and variety of species represented, despite not a few errors and repetitions, place it above any other herbarium of the century, except for the Aldrovandi one (limited to the Bologna flora).

In Arcevia, C. assumed a position of authority despite not holding public office. He was often consulted to resolve disputes and rivalries; he contributed to the founding of a Monte di pietà and, especially during a terrible famine in 1590, dedicated himself to generous philanthropic activities.

He died in Arcevia (Ancona) on January 30, 1600, and was buried in the church of S. Francesco.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (Siena, March 12, 1501 – Trento, 1578) was an Italian humanist, doctor, and botanist.

Biography

Origins and apprenticeship

He was born in Siena in 1501 (1500 BC), but he spent his childhood in Venice, where his father, Francesco, practiced medicine.

Just large enough, his father sent him to Padua, where he began studying various humanities subjects, such as Latin, ancient Greek, rhetoric, and philosophy. However, Pietro Andrea became more passionate about medicine, and he graduated in this field in 1523. When his father died, he returned to Siena, but the city was shaken by a feud between rival families, so he decided to go to Perugia to study surgery under the master Gregorio Caravita.

From there, he moved to Rome, where he continued his medical studies at the Santo Spirito Hospital and the Xenodochium San Giacomo for the incurables, but in 1527, due to the sack by the Landsknechts, he decided to leave the city and move to Trento, where he remained for thirty years.

In Trento and Gorizia

Mattioli effigies at the Museo della Specola, Florence

He then went to live in Val di Non, and soon his fame reached the ears of Prince-Bishop Bernardo Clesio, who invited him to the castle of Buonconsiglio, offering him the position of counselor and personal doctor. It was to Bishop Clesio, to whom Mattioli later dedicated two of his early works, that he dedicated a poem in verse called The Great Palace of the Cardinal of Trento, which described in detail the Renaissance-style renovation that the bishop ordered for his castle. Published in 1539 by Marcolini in Venice, the poem used the structure of ottava rima, similar to that used by Boccaccio, but it was not on the same level as the works of other poets of the time.

In 1528, Mattioli married a Trentino woman, a woman named Elisabetta whose surname is unknown, and he had a son. Five years later, he published his first pamphlet, Morbi Gallici Novum ac Utilissimum Opusculum, and began working on his work about Dioscoride Anazarbeo. In 1536, Mattioli accompanied Bernardo Clesio as a doctor to Naples for a meeting with Emperor Charles V. Returning to Trento, with the death of Bernardo Clesio in 1539, Cristoforo Madruzzo succeeded him to the episcopal throne, but he already had a doctor, so Mattioli decided to move to Cles, where he soon found himself in financial difficulties.

Between 1541 and 1542, Mattioli moved again to Gorizia, where he practiced medicine and worked on translating Dioscorides' De Materia Medica from Greek, adding his speeches and comments. Then, finally, in 1544, he published his main work for the first time, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia medicinale translated into the Italian vernacular by M. Pietro Andrea Matthioli, a Sienese doctor, with extensive speeches, comments, learned annotations, and censures by the same interpreter, more commonly known as the Discourses of Pier Andrea Mattioli on the work of Dioscorides. The first edition was published in Venice without illustrations and dedicated to Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, Prince-Bishop of Trento and Bressanone.

Note that Mattioli not only translated Dioscoride's work but also completed it with the results of a series of studies on plants with properties still unknown at the time, transforming the Discorsi into a fundamental work on medicinal plants, a true reference point for scientists and doctors for several centuries.

In 1548, he published the second edition of Mattioli's Discorsi on Dioscoride, with the addition of the sixth book on remedies against poisons, considered apocryphal by many. Subsequently, many other editions were published, some without his approval. He also received many criticisms from notable figures of the time. In 1554, the first Latin edition of Mattioli's Discorsi was published, also called Commentarii, or Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis plantarum & animalium imaginibus, eodem authore; it was the first edition to be illustrated and is dedicated to Ferdinand I of Austria, then Prince of the Romans, Pannonia, and Bohemia, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Count and Lord of Tyrol. It was later translated into French (1561), Czech (1562), and German (1563).

To the imperial court

Funerary monument of Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Cathedral of Trento

Following great fame and success, Ferdinando I called Mattioli to Prague as the personal doctor of his second son, Archduke Ferdinand. However, before departing, the inhabitants of Gorizia decided to gift him a precious gold chain, which can be seen in many of his depictions, as a sign of esteem and affection. In 1555, Mattioli moved to Prague, although already the following year he was forced, albeit reluctantly, to accompany Archduke Ferdinand to Hungary in the war against the Turks.

In 1557, he married for the second time to a noblewoman from Gorizia, Girolama di Varmo, with whom he had two children, Ferdinando in 1562 and Massimiliano in 1568, whose names are clearly chosen in honor of the royal house. On July 13, 1562, Mattioli was appointed by Ferdinando as Aulic Councillor and noble of the Holy Roman Empire. When Ferdinando died in 1564, Maximilian II had just ascended to the throne. For a while, Mattioli remained in the service of the new sovereign, but in 1571 he decided to retire permanently to Trento. Two years earlier, he had married for the third time, again with a Trentino woman, a certain Susanna Caerubina.

In 1578 (1577 by the incamation date), Pietro Andrea Mattioli died of the plague in Trento in January or February. His sons Ferdinando and Massimiliano dedicated a magnificent funeral monument to him in the city's Duomo (still existing today), thanks to his role as archiatre, physician to the Council of Trent, and therefore to Prince-Bishop Bernardo Clesio.

The plant genus Matthiola was named by botanist Robert Brown in honor of Mattioli.

Mattioli is the standard abbreviation used for plants described by Pietro Andrea Mattioli.

Check the list of plants assigned to this author by the IPNI.

Opere

Trifolium acetosum (Oxalis) taken from Commentarii

Commentaries on six books by Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus on medical materia, 1565

1533, A New and Very Useful Little Work on the French Disease

1535, Liber de Morbo Gallico, dedicated to Bernardo Clesio

1536, On the Method of Treating the Gallic Disease

1539, The Great Palace of the Cardinal of Trento

1544, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo, five books on history and medicinal matter, translated into the vernacular Italian language by M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo, a Sienese doctor, with extensive discourses, commentaries, and learned annotations and censures by the same interpreter, called Discourses.

1548, Italian translation of Ptolemy's Geography

1554, Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentaries, on the six books of Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus, on Materia Medica, with the addition of many images of plants and animals, also by the same author, called Commentaries.

1558, Apology Against Amatus Lusitanus

1561, Five Books of Medical Letters

(LA) Commentaries in six books by Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus on medical matter, Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1565.

1569, Small Treatise on the Faculties of Simple Medicines

Compendium of Plants, All Together with Their Illustrations

(LA) De plantis, Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1571.

(LA) De plantis, Frankfurt am Main, Johann Feyerabend, 1586.

Dioscoride Pedanio

You

Discussion

Read

Modify

Edit wikitext

Chronology

Tools

Medieval miniature, from the Vienna Dioscorides.

Dioscoride Pedanio (in ancient Greek: Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης?, Pedánios Dioskourídēs; Anazarbo, circa 40 – circa 90) was an ancient Greek botanist and physician who lived during the Roman Empire in the time of Nero.

Dante mentions him in the fourth canto of the Inferno, in limbo, with the epithet of 'good receiver of which,' that is, of the quality of herbs.

Opere

The same subject in detail: De materia medica.

Pages with cumin and dill from the Arabic version of 1334 of De materia medica, preserved at the British Museum in London.

Dioscorides of Anazarbo is mainly known as the author of the treatise On Medical Material. It is an herbal originally written in Greek, which had a certain influence on medieval medicine. It remained in use, in a spurious form of translations and commentaries, until around the 17th century, when it was surpassed by the advent of modern medicine.

Dioscoride's portrait in the 'De natura medica' within a 13th-century Arabic version.

Dioscoride also describes a rudimentary machine for distillation, equipped with a tank featuring a sort of upper head, from which vapors enter a structure where they are cooled and then undergo condensation. These elements are usually absent in medieval distillation apparatuses.

Besides being known in the Greek and Roman area, the work was also known to Arabs and in Asia. In fact, several manuscripts of Arabic and Indian translations of the work have come down to us.

A large number of illustrated manuscripts attest to the dissemination of the work. Some of them date back to approximately the period from the 5th to the 7th century AD; the most famous among them is the Codex Aniciae Julianae. The main Italian translation of Dioscorides was published during the cinquecento, with the publication of 'Discussions... in the six books of Pedanius Dioscorides... on medicinal matter,' by Valgrisi in 1568, by Mattioli. The printed edition by Mattioli included a commentary and high-quality illustrations that made plant recognition easier.

Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi

I have already been writing for some months now to Your Lordship with a miniature drawing of your hand, the most beautiful I have ever seen in my entire life, and I believe that Your Lordship, in making drawings with a brush, has no equal in the world... I tell you only that the drawing you sent me has become very dear to me, and I keep it guarded as a treasure, just as I do my joys, and if I could see the book in which I think there are hundreds of such drawings, I would consider it a great favor from Heaven. For I truly do not know what I could see with more satisfaction in my heart and soul, and who knows, perhaps one day Rome will see me again: if only I am

old

This is a passage from a letter sent to 'The Most Magnificent... Mr. Gherardo Cibo' on November 19, 1565, glued onto the front cover of an illustrated manuscript (Add. 22333) preserved at the British Library. Its counterpart, the Dioscoride by Cibo and Mattioli (Add. 22332), ranks among the most significant botanical manuscripts held at the London library. The author of the letter was Pietro Andrea Mattioli, a naturalist in the service of the Habsburg court in Prague, who had long been engaged in the search for images of plants to include in his commentary on the work of the Greek physician Dioscorides—the Commentaries or Discourses—a milestone in the history of European botany.

Art and Botany

The artist to whom Mattioli directed highly flattering compliments was Gherardo Cibo, admired also by other eminent scientists, including the Roman Andrea Bacci and the Bolognese Ulisse Aldrovandi. Nevertheless, the figure of Gherardo Cibo disappeared from the stage of history (and also from the artistic and scientific spheres), having chosen to live in voluntary isolation, away from the elitist and editorial circuits of his time. It was only at the beginning of the last century that a learned librarian from the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome—Enrico Celani—attributed to him five 'dusty volumes, poorly preserved, damaged in their bindings' of an herbarium containing 1,800 dried specimens, and based on a now-lost diary, he revealed some episodes of Gherardo's life.

Who was our character? Great-grandson of Pope Innocent VIII (Giovanbattista Cibo), he was born in Rome in 1512, where he spent much of his early youth, possibly destined for an ecclesiastical career. As a teenager, he experienced the tragedy of the Sack of the Landsknechts, which forced him to seek refuge in the Marche, his mother's region, related to the Dukes of Urbino. Later residing for some time in Bologna, it seems he attended university lectures by the renowned botanist Luca Ghini, from whom he developed an interest in the plant world and skill in preparing dried herbariums. Gherardo then had the opportunity to accompany his father Aranino on two important papal embassies: the first took them to Regensburg, where they met Charles V of Habsburg; the second to Paris, where they met King Francis I, and then accompanied him on the return journey to the Netherlands. During these travels, he did not neglect to study numerous plants and perhaps also became acquainted with Flemish artistic production, which would later have a significant influence on his work.

Dioscorides of Food and Mattioli. 1564-1584 circa. The British Library, London Ms. 22332. Leather binding with titles and gold embellishments, housed inside a leather box with gold decorations. 370 pages with 168 full-page miniatures. In excellent condition. Edition of 987 numbered copies (our no. 311). The volume on the authors' studies is missing.

The brilliant artist and botanist Gherardo Cibo (1512-1600), great-grandson of Pope Innocent VIII, is the creator of the splendid miniatures that illuminate this extraordinary manuscript. The text is that of Pietro Andrea Mattioli's Discourses (1501-1577), an eminent naturalist and personal physician to Ferdinand II. In the Discourses, the contents of the famous De materia Medica by Dioscorides are commented upon, with the addition of many new plant species, some recently discovered in Tyrol, the East, and America. Unlike those in Dioscorides' treatise, these species were included in the work for their uniqueness and beauty. The manuscript, which would become a precursor of modern botany, was already highly successful in its time. Among the various works Cibo painted based on Mattioli's writings, this is the most beautiful, as evidenced by a letter in which Mattioli himself warmly congratulates Cibo on the outcome of his work. A fundamental work for lovers of medicine, botany, and painting in general, due to the meticulous detail and colors with which not only the different plant species are illustrated but also the vibrant landscapes that serve as their background and often depict their natural habitat.

Food, Gherardo

Born in Genoa in 1512 to Aranino and Bianca Vigeri Della Rovere, a relative of Francesco Maria I, Duke of Urbino, and grandson of Marco Vigeri, Bishop of Senigallia. The paternal family belonged to a branch of the Cibo family descended from Teodorina, daughter of Giovanni Battista Cibo, who became Pope Innocent VIII.

Lady and Gherardo Usodimare of Genoa were the parents of Aranino, born in 1484, who was the custodian of the Camerino fortress and died in Sarzana in 1568, after obtaining the title of Count of the Lateran Palace. From Aranino's marriage, who had received from the Pope the concession to assume and transmit the surname Cibo, and Bianca Vigeri, were born, in addition to C., Marzia, Maddalena, Scipione, and Maria. The two sisters, Marzia and Maddalena, respectively married Count Antonio Maurugi of Tolentino and Domenico Passionei, gonfaloniere of Urbino. From this family, two centuries later, Cardinal Domenico Passionei was born, a renowned bibliophile who made a significant contribution to the collection of the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome. Scipione, born in Genoa in 1531, traveled extensively across Europe and died in Siena in 1597. The youngest sister, Maria, was a nun at the monastery of S. Agata in Arcevia.

After an initial period of residence in his hometown, C. spent his adolescence in Rome, where he arrived following the Duchess of Camerino, Caterina Cibo da Varano, a relative, in 1526 for study purposes and also to pursue an ecclesiastical career. But the sack of Rome forced him to leave immediately from the city invaded by the Landsknecht. C. stayed for a few months in Camerino with Duke Giovanni Maria da Varano. Upon his death in August 1529, he followed Francesco Maria Della Rovere, captain general of the Church's armies, in a series of military campaigns in the Po Valley and Bologna, where he had gone for Charles V's coronation. In Bologna, C. was able to attend Luca Ghini's botany lessons until 1532.

This period was very important for C.'s scientific education, as he learned from Ghini the method of collecting, cataloging, and mounting plants for the creation of an herbarium. It is known that Ghini himself collected dried plants, which he sometimes sent to contemporary botanists like Mattioli; however, his herbarium, like those of his students John Falconer and William Turner, was destroyed.

Even during his Bologna years, C. was able to begin collecting material for his herbarium. However, it was mainly during his travels in subsequent years that he had the opportunity to expand his research scope. In 1532, in fact, his father took him to the court of Charles V, where he was tasked with negotiating the marriage, which later did not take place, between Giulia da Varano, daughter of Caterina Cibo, and Charles of Lannoy, son of the Prince of Sulmona. This two-year journey through the valley of the Adige and the Danube, from Trento to Ingolstadt and Regensburg, in the Upper Palatinate, was a valuable opportunity for C. to conduct botanical research, which he continued even upon returning to Italy.

-ALT

In 1534, he was at Agnano near Lorenzo Cibo, a relative of his, and was able to undertake detailed botanical and mineralogical excursions around Pisa. In 1539, he set out again for Germany, accompanying Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, a learned and generous man who had been his study companion in Bologna. His motivation for this journey was not only the scientific aim of collecting material for his herbarium and engaging with foreign botanists but also the religious purpose of contributing to the fight against Lutheranism. However, it was his deep religiosity that convinced him to leave the armies and return to the peace of his studies. It is also possible that his decision was influenced by the political conflict conducted by the Farnese against the Cibo and Della Rovere families over the possession of Camerino. In fact, the Camerino state, an ancient lordship of the Varano family, had been transferred, by order of Pope Paul III Farnese, to Ottavio, his nephew; faced with the conflicts between his family and that of his powerful protector Alessandro Farnese, he preferred to retreat into scholarly solitude at Rocca Contrada (the present-day Arcevia) in 1540.

He still took some trips, to the Marche, Umbria, and Rome, where he visited in 1553; but he practically spent the rest of his life always in Arcevia, from where he set out for daily excursions in the surroundings and on the Marche Apennines to collect plants and minerals. Not lacking in marked artistic talents, he used to paint the plants he collected with a fine taste for detail; this activity, alongside and as an extension of his naturalistic curiosity, was not merely a pastime, as his paintings and drawings, preserved in Arcevia, are of notable artistic merit, especially the landscapes. Information about his daily activities is known through a Diary that C. kept starting in 1553, of which Celani (1902, pp. 208-11) reports some excerpts (although no news of it is currently available).

A meticulous and precise scholar, C. had the habit of annotating and supplementing the works he read with notes and drawings, such as those by Pliny, Leonhart Fuchs, and Garcia Dall'Orto. Notably, there is an edition of Dioscorides (Venice 1568) by the Sienese botanist Pierandrea Mattioli, a friend of C. and with whom he corresponded through letters, illustrated with miniatures and drawings for Cardinal Della Rovere (today preserved at the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome, shelf mark Ae q II). He also prepared various drawings for the Cardinal of Urbino and other correspondents, including remarkable large zoological plates (also in the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome, MS. 2).

Despite his withdrawn life, which was rather unusual for a scientist, C. was in correspondence with the most experienced botanists of his time, from Ulisse Aldrovandi to Andrea Bacci, from Fuchs to the aforementioned Mattioli. There is no record of his relations with Cesalpino, who was also a student of Ghini (not in Bologna, but in Pisa) and in correspondence with Aldrovandi and Bacci. On the other hand, the organizational criteria of Cesalpino's herbarium differ from those of C., whose herbarium is not systematically arranged but alphabetical, like that of Aldrovandi. This coincidence of method can be attributed both to their common master Ghini and to the close relations between Aldrovandi and Cibo. In a letter from 1576 (published by De Toni, pp. 103-108), Aldrovandi demonstrates that he is familiar with C.'s herbarium and possesses its index; he sends his friend some clarifications about various plants, including Lunaria tonda (which C. had sent him a drawing), and about a fabulous two-headed snake, the amphisbaena. Regarding this curious reptile, C.: had written, according to Aldrovandi (in Serpentum et draconum historiae libri duo, Bononiae 1640 [but 1639], p. 238), a memoir in which he claimed to have seen it. It seems certain, however, that he had sent several valuable pieces to the Aldrovandi natural museum, and that this relationship had both stimulating effects for both parties. Besides the aforementioned memoir, only cited by Aldrovandi, there is no record of other works by C., as such works cannot be considered those of other authors (preserved at the Biblioteca Angelica), which he commented on with medical, botanical, and mineralogical annotations, or the recipes scattered in letters (e.g., one published by Celani, 1902, pp. 222-26). This justifies the silence of contemporary catalogs and botanical works about him.

The attribution to C. of the herbarium preserved at the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome and studied particularly by E. Celani and O. Penzig sparked a lively controversy between Celani on one side and Chiovenda and De Toni on the other during the years 1907-1909, as the latter argued that the author of most of this herbarium was not C., but the Viterbese botanist Francesco Petrollini, also part of the Aldrovandi circle, in fact the master and guide of Aldrovandi in collecting plant specimens. It is not possible to give a definitive answer to the question; what is certain is that the herbarium kept at Angelica is the oldest among those that have come down to us. It consists of five volumes: the first, called "A" by Penzig, is quite damaged and contains three hundred twenty-two unnumbered sheets with four hundred ninety specimens of alpine and subalpine flora, without any systematic criterion (this could be, contrary to Chiovenda's opinion, the herbarium of C. mentioned by Aldrovandi in the above letter); the other four volumes (herbarium "B"), completed before 1551, are altogether made up of nine hundred thirty-eight sheets with one thousand three hundred forty-six specimens, many of the same species. The number and variety of species represented, despite not a few errors and repetitions, place it above any other herbarium of the century, except for the Aldrovandi one (limited to the Bologna flora).

In Arcevia, C. assumed a position of authority despite not holding public office. He was often consulted to resolve disputes and rivalries; he contributed to the founding of a Monte di pietà and, especially during a terrible famine in 1590, dedicated himself to generous philanthropic activities.

He died in Arcevia (Ancona) on January 30, 1600, and was buried in the church of S. Francesco.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (Siena, March 12, 1501 – Trento, 1578) was an Italian humanist, doctor, and botanist.

Biography

Origins and apprenticeship

He was born in Siena in 1501 (1500 BC), but he spent his childhood in Venice, where his father, Francesco, practiced medicine.

Just large enough, his father sent him to Padua, where he began studying various humanities subjects, such as Latin, ancient Greek, rhetoric, and philosophy. However, Pietro Andrea became more passionate about medicine, and he graduated in this field in 1523. When his father died, he returned to Siena, but the city was shaken by a feud between rival families, so he decided to go to Perugia to study surgery under the master Gregorio Caravita.

From there, he moved to Rome, where he continued his medical studies at the Santo Spirito Hospital and the Xenodochium San Giacomo for the incurables, but in 1527, due to the sack by the Landsknechts, he decided to leave the city and move to Trento, where he remained for thirty years.

In Trento and Gorizia

Mattioli effigies at the Museo della Specola, Florence

He then went to live in Val di Non, and soon his fame reached the ears of Prince-Bishop Bernardo Clesio, who invited him to the castle of Buonconsiglio, offering him the position of counselor and personal doctor. It was to Bishop Clesio, to whom Mattioli later dedicated two of his early works, that he dedicated a poem in verse called The Great Palace of the Cardinal of Trento, which described in detail the Renaissance-style renovation that the bishop ordered for his castle. Published in 1539 by Marcolini in Venice, the poem used the structure of ottava rima, similar to that used by Boccaccio, but it was not on the same level as the works of other poets of the time.

In 1528, Mattioli married a Trentino woman, a woman named Elisabetta whose surname is unknown, and he had a son. Five years later, he published his first pamphlet, Morbi Gallici Novum ac Utilissimum Opusculum, and began working on his work about Dioscoride Anazarbeo. In 1536, Mattioli accompanied Bernardo Clesio as a doctor to Naples for a meeting with Emperor Charles V. Returning to Trento, with the death of Bernardo Clesio in 1539, Cristoforo Madruzzo succeeded him to the episcopal throne, but he already had a doctor, so Mattioli decided to move to Cles, where he soon found himself in financial difficulties.

Between 1541 and 1542, Mattioli moved again to Gorizia, where he practiced medicine and worked on translating Dioscorides' De Materia Medica from Greek, adding his speeches and comments. Then, finally, in 1544, he published his main work for the first time, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia medicinale translated into the Italian vernacular by M. Pietro Andrea Matthioli, a Sienese doctor, with extensive speeches, comments, learned annotations, and censures by the same interpreter, more commonly known as the Discourses of Pier Andrea Mattioli on the work of Dioscorides. The first edition was published in Venice without illustrations and dedicated to Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, Prince-Bishop of Trento and Bressanone.

Note that Mattioli not only translated Dioscoride's work but also completed it with the results of a series of studies on plants with properties still unknown at the time, transforming the Discorsi into a fundamental work on medicinal plants, a true reference point for scientists and doctors for several centuries.

In 1548, he published the second edition of Mattioli's Discorsi on Dioscoride, with the addition of the sixth book on remedies against poisons, considered apocryphal by many. Subsequently, many other editions were published, some without his approval. He also received many criticisms from notable figures of the time. In 1554, the first Latin edition of Mattioli's Discorsi was published, also called Commentarii, or Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis plantarum & animalium imaginibus, eodem authore; it was the first edition to be illustrated and is dedicated to Ferdinand I of Austria, then Prince of the Romans, Pannonia, and Bohemia, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Count and Lord of Tyrol. It was later translated into French (1561), Czech (1562), and German (1563).

To the imperial court

Funerary monument of Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Cathedral of Trento

Following great fame and success, Ferdinando I called Mattioli to Prague as the personal doctor of his second son, Archduke Ferdinand. However, before departing, the inhabitants of Gorizia decided to gift him a precious gold chain, which can be seen in many of his depictions, as a sign of esteem and affection. In 1555, Mattioli moved to Prague, although already the following year he was forced, albeit reluctantly, to accompany Archduke Ferdinand to Hungary in the war against the Turks.

In 1557, he married for the second time to a noblewoman from Gorizia, Girolama di Varmo, with whom he had two children, Ferdinando in 1562 and Massimiliano in 1568, whose names are clearly chosen in honor of the royal house. On July 13, 1562, Mattioli was appointed by Ferdinando as Aulic Councillor and noble of the Holy Roman Empire. When Ferdinando died in 1564, Maximilian II had just ascended to the throne. For a while, Mattioli remained in the service of the new sovereign, but in 1571 he decided to retire permanently to Trento. Two years earlier, he had married for the third time, again with a Trentino woman, a certain Susanna Caerubina.

In 1578 (1577 by the incamation date), Pietro Andrea Mattioli died of the plague in Trento in January or February. His sons Ferdinando and Massimiliano dedicated a magnificent funeral monument to him in the city's Duomo (still existing today), thanks to his role as archiatre, physician to the Council of Trent, and therefore to Prince-Bishop Bernardo Clesio.

The plant genus Matthiola was named by botanist Robert Brown in honor of Mattioli.

Mattioli is the standard abbreviation used for plants described by Pietro Andrea Mattioli.

Check the list of plants assigned to this author by the IPNI.

Opere

Trifolium acetosum (Oxalis) taken from Commentarii

Commentaries on six books by Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus on medical materia, 1565

1533, A New and Very Useful Little Work on the French Disease

1535, Liber de Morbo Gallico, dedicated to Bernardo Clesio

1536, On the Method of Treating the Gallic Disease

1539, The Great Palace of the Cardinal of Trento

1544, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo, five books on history and medicinal matter, translated into the vernacular Italian language by M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo, a Sienese doctor, with extensive discourses, commentaries, and learned annotations and censures by the same interpreter, called Discourses.

1548, Italian translation of Ptolemy's Geography

1554, Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentaries, on the six books of Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus, on Materia Medica, with the addition of many images of plants and animals, also by the same author, called Commentaries.

1558, Apology Against Amatus Lusitanus

1561, Five Books of Medical Letters

(LA) Commentaries in six books by Pedacius Dioscorides Anazarbeus on medical matter, Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1565.

1569, Small Treatise on the Faculties of Simple Medicines

Compendium of Plants, All Together with Their Illustrations

(LA) De plantis, Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1571.

(LA) De plantis, Frankfurt am Main, Johann Feyerabend, 1586.

Dioscoride Pedanio

You

Discussion

Read

Modify

Edit wikitext

Chronology

Tools

Medieval miniature, from the Vienna Dioscorides.

Dioscoride Pedanio (in ancient Greek: Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης?, Pedánios Dioskourídēs; Anazarbo, circa 40 – circa 90) was an ancient Greek botanist and physician who lived during the Roman Empire in the time of Nero.

Dante mentions him in the fourth canto of the Inferno, in limbo, with the epithet of 'good receiver of which,' that is, of the quality of herbs.

Opere

The same subject in detail: De materia medica.

Pages with cumin and dill from the Arabic version of 1334 of De materia medica, preserved at the British Museum in London.

Dioscorides of Anazarbo is mainly known as the author of the treatise On Medical Material. It is an herbal originally written in Greek, which had a certain influence on medieval medicine. It remained in use, in a spurious form of translations and commentaries, until around the 17th century, when it was surpassed by the advent of modern medicine.

Dioscoride's portrait in the 'De natura medica' within a 13th-century Arabic version.

Dioscoride also describes a rudimentary machine for distillation, equipped with a tank featuring a sort of upper head, from which vapors enter a structure where they are cooled and then undergo condensation. These elements are usually absent in medieval distillation apparatuses.

Besides being known in the Greek and Roman area, the work was also known to Arabs and in Asia. In fact, several manuscripts of Arabic and Indian translations of the work have come down to us.

A large number of illustrated manuscripts attest to the dissemination of the work. Some of them date back to approximately the period from the 5th to the 7th century AD; the most famous among them is the Codex Aniciae Julianae. The main Italian translation of Dioscorides was published during the cinquecento, with the publication of 'Discussions... in the six books of Pedanius Dioscorides... on medicinal matter,' by Valgrisi in 1568, by Mattioli. The printed edition by Mattioli included a commentary and high-quality illustrations that made plant recognition easier.

Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi

I have already been writing for some months now to Your Lordship with a miniature drawing of your hand, the most beautiful I have ever seen in my entire life, and I believe that Your Lordship, in making drawings with a brush, has no equal in the world... I tell you only that the drawing you sent me has become very dear to me, and I keep it guarded as a treasure, just as I do my joys, and if I could see the book in which I think there are hundreds of such drawings, I would consider it a great favor from Heaven. For I truly do not know what I could see with more satisfaction in my heart and soul, and who knows, perhaps one day Rome will see me again: if only I am

old

This is a passage from a letter sent to 'The Most Magnificent... Mr. Gherardo Cibo' on November 19, 1565, glued onto the front cover of an illustrated manuscript (Add. 22333) preserved at the British Library. Its counterpart, the Dioscoride by Cibo and Mattioli (Add. 22332), ranks among the most significant botanical manuscripts held at the London library. The author of the letter was Pietro Andrea Mattioli, a naturalist in the service of the Habsburg court in Prague, who had long been engaged in the search for images of plants to include in his commentary on the work of the Greek physician Dioscorides—the Commentaries or Discourses—a milestone in the history of European botany.

Art and Botany

The artist to whom Mattioli directed highly flattering compliments was Gherardo Cibo, admired also by other eminent scientists, including the Roman Andrea Bacci and the Bolognese Ulisse Aldrovandi. Nevertheless, the figure of Gherardo Cibo disappeared from the stage of history (and also from the artistic and scientific spheres), having chosen to live in voluntary isolation, away from the elitist and editorial circuits of his time. It was only at the beginning of the last century that a learned librarian from the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome—Enrico Celani—attributed to him five 'dusty volumes, poorly preserved, damaged in their bindings' of an herbarium containing 1,800 dried specimens, and based on a now-lost diary, he revealed some episodes of Gherardo's life.

Who was our character? Great-grandson of Pope Innocent VIII (Giovanbattista Cibo), he was born in Rome in 1512, where he spent much of his early youth, possibly destined for an ecclesiastical career. As a teenager, he experienced the tragedy of the Sack of the Landsknechts, which forced him to seek refuge in the Marche, his mother's region, related to the Dukes of Urbino. Later residing for some time in Bologna, it seems he attended university lectures by the renowned botanist Luca Ghini, from whom he developed an interest in the plant world and skill in preparing dried herbariums. Gherardo then had the opportunity to accompany his father Aranino on two important papal embassies: the first took them to Regensburg, where they met Charles V of Habsburg; the second to Paris, where they met King Francis I, and then accompanied him on the return journey to the Netherlands. During these travels, he did not neglect to study numerous plants and perhaps also became acquainted with Flemish artistic production, which would later have a significant influence on his work.