Gaston Phébus - Libro della caccia di Gaston Febus - 1387-2017

Founded and directed two French book fairs; nearly 20 years of experience in contemporary books.

Bidder 3533 Bidder 3533 | €460 | |

|---|---|---|

Bidder 0774 Bidder 0774 | €440 | |

Bidder 1147 Bidder 1147 | €420 | |

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123641 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

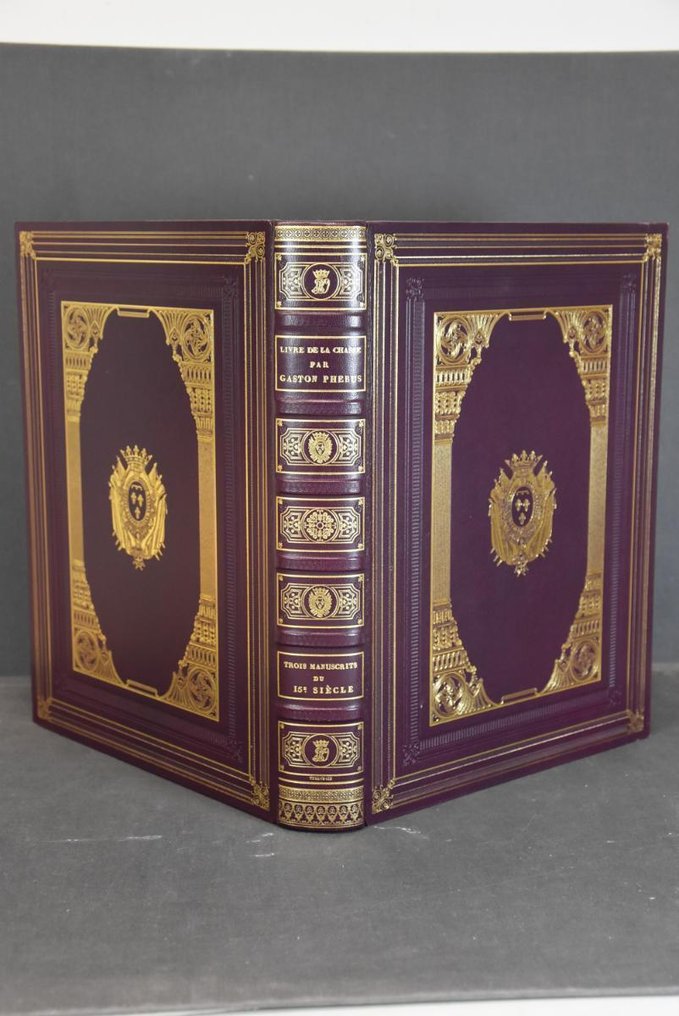

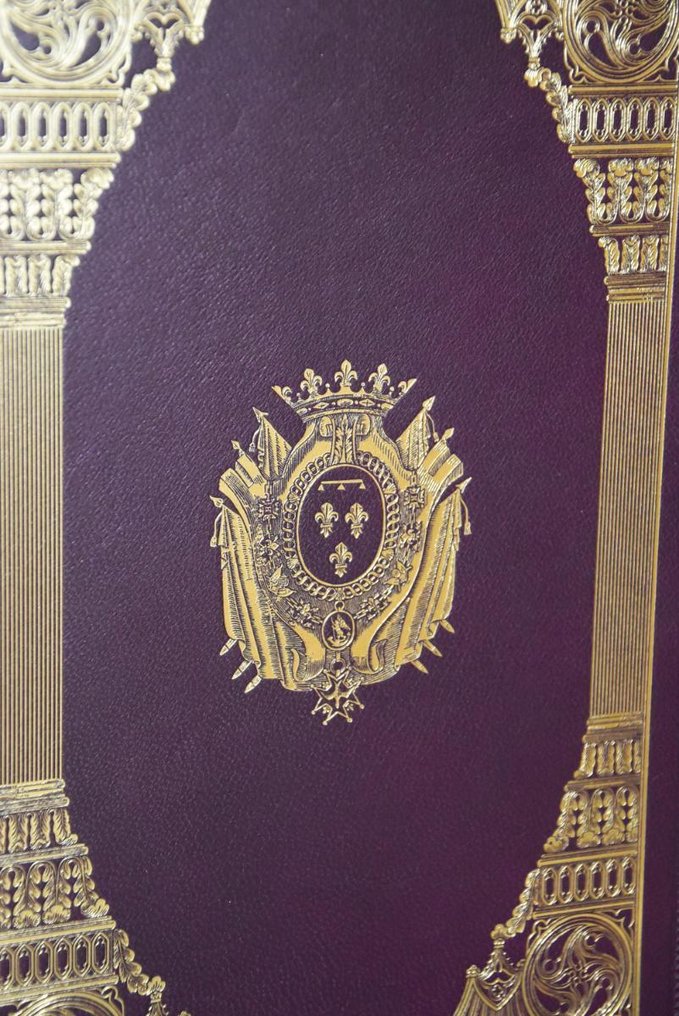

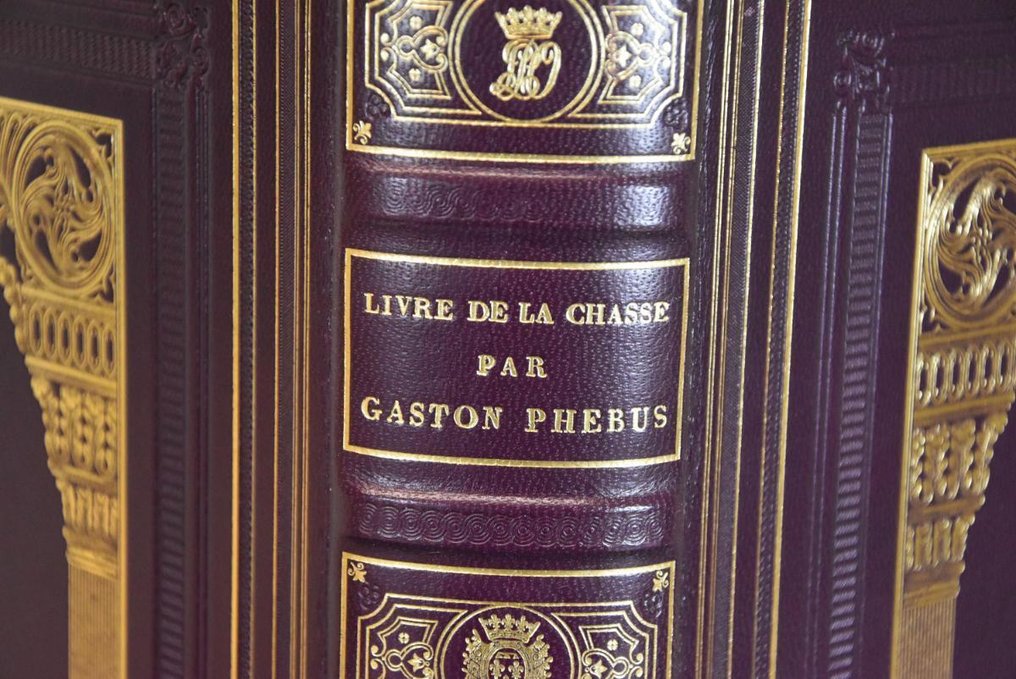

Libro della caccia di Gaston Febus by Gaston Phébus, a limited edition (987 copies, ours 488) published in 2017 by M. Moleiro Editor, S.A. in French with original language indicated, bound in pelle leather, 436 pages, 37 cm by 27.5 cm, containing 87 miniatures and in excellent condition.

Description from the seller

Book of the Hunt by Gaston Febus. 1387-1389. National Library of France, Paris (Francais 616). Publisher Moleiro, 2017. Leather binding enriched with gold and blind embossing, in a leather case. 436 pages. 87 miniatures. Edition of 987 copies (ours no. 488). In excellent condition. Some minimal, negligible scuffing at the corners.

The Book of Hunting was written between 1387 and 1389. More precisely, it was dictated to a scribe by Gaston Fébus, Count of Foix and Viscount of Béarn, and dedicated to the Duke of Burgundy, Philip II the Bold. A man of complex personality and tumultuous life, Fébus was not only a great hunter but also a passionate lover of books on hunting and falconry. The volume he carefully composed became the reference work for all enthusiasts of the art of hunting until the end of the 16th century.

Of the 44 preserved copies, the French manuscript 616 is undoubtedly the most beautiful and complete. In addition to the actual Book of the Hunt, this manuscript also contains the Book of Prayers, also written by Gaston Fébus, as well as a second treatise called 'Déduits de la chasse' ('Pleasures of the Hunt') authored by Gace de la Buigne.

To illustrate its pages, there are 87 miniatures of extraordinary quality, which are among the most fascinating productions of Parisian miniatures from the early 15th century. Furthermore, there are certainly not many books dedicated to the art of hunting with a pictorial richness comparable to that of Bibles.

The teachings

The Book of Hunting was until the end of the 16th century the 'breviary' of hunting and game management followers. It is a manual of instructions for hunters, structured into seven chapters with a prologue and an epilogue, which describes in detail how to carry out a hunt. Written for young apprentices, the text offers concise teachings but presents them with the liveliness of someone passionate about the subject. Gaston Fébus does not forget the importance of the animals involved in hunting, especially dogs, faithful companions of hunters. He shares his knowledge about different breeds and their respective behaviors, training, feeding, and even how to treat various illnesses. It is evident that hunting, the passion par excellence of medieval lords, is not just a pastime, as it requires many skills and qualities both human and professional.

However, focusing solely on the technical content would be like overlooking the essence of Gaston Fébus's work. Beyond the realm of hunting, this personal and original treatise is primarily a product of its time, when the idea of sin and the fear of condemnation were omnipresent. In composing the work, Gaston Fébus presents hunting as an exercise in redemption that would grant the hunter direct access to Paradise. In fact, the physical activity of hunting, which already requires a certain level of skill, is an excellent antidote to idleness, the root of all evil. At the same time, it trains body and mind in prudence, thus avoiding any possibility of sin. What this work reveals is nothing other than the tragedy of human existence, the quest for eternal life after passing through the earthly world, which is ultimately where we earn it.

The Illustration

The miniatures of the Book of Chess were commissioned from various artists, including a group known as 'corrente Bedford.' Among them stands out the Master of the Adelfi for his sense of observation and decorative stylization, which make his works the most representative examples of the international Gothic style. Associated with this group is also the Master of Egerton, whose style is close to that of the Limbourg brothers. Finally, we believe we can also recognize in him the Master of the Othea Epistle, whose works are characterized by a thicker stroke, different from the delicate craftsmanship typical of the 'corrente Bedford,' with which he seems to have collaborated only on this manuscript.

Mastering the codes of representation of the Middle Ages perfectly, the miniaturists put their art at the service of Gaston Fébus's pedagogical project. The backgrounds are elegantly decorated with miniatures that, in a reduced format, resemble the tapestries of the era. The aim is not to depict a real space, but rather to rely on a hierarchy of values. Everything is cast and reproduced in a coherent discourse. The passage of time is well evoked by the age of the characters, their activities, their relationships, and their position in space: thus creating a parallel between hunting and the process of learning about life. The mimetic yet orderly character of the elements gives the whole a broad scope and a certain air of serenity, guiding the reader through the secrets of a hunting conducted with masterful skill. More than a lesson in hunting, it is a lesson in life.

History of the Code

Throughout its history, the manuscript changed owners numerous times. It first belonged to Aymar de Poitiers (late 15th century) and then to Bernando Cles, bishop of Trento, who shortly before 1530 gifted it to Ferdinand I of Austria, a prince of Spain and archduke of Austria, brother of Charles V. In 1661, the Marquis of Vigneau also gifted the Book of the Hunt to King Louis XIV (reigned 1643-1715), who ordered it to be kept in the Royal Library. In 1709, it was removed from the library and came into the hands of the heir to France, the Duke of Burgundy, who stored it in the Cabinet du Roi. In 1726, the manuscript reappeared in the library of the Château of Rambouillet, owned by Louis XIV’s illegitimate son, Louis Alexander of Bourbon. After his death, it was inherited by his son, the Duke of Penthièvre. Later, it belonged to the Orleans family and finally to King Louis-Philippe, who in 1834 brought it to the Louvre. After the 1848 revolution, it was returned to the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gastone di Foix, known as Febo (in Catalan: Gastó III de Foix, in Castilian: Gastón III Febus, in Occitan: Gaston II de Fois-Bearn, and in French: Gaston III de Foix-Béarn; Orthez, April 30, 1331 – Sauveterre-de-Béarn, August 1, 1391), was an important feudal lord of Gascony and Languedoc. He was Count of Foix, Viscount of Béarn, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount of Marsan, and Viscount of Lautrec from 1343 until his death.

Gastone received the nickname of Phoebus, both for his beauty, his love for art, and also because he had the sun as an emblem.

Family background

Gastone Febo, according to Pierre de Guibours, also known as Père Anselme de Sainte-Marie or more briefly Père Anselme, and according to the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix was the eldest legitimate son of the Count of Foix, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount consort of Béarn, Viscount of Marsan, and Viscount of Lautrec, Gastone II, and his wife, Leonora of Cominges, who was the daughter of Count Bernardo VII of Cominges and Laura of Monfort, as evidenced by the extract from the Mars MCCCXCVI of the Histoire généalogique de la maison d'Auvergne.

Gastone II of Foix-Béarn, according to both Père Anselme and the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix, was the eldest son of the Count of Foix, Viscount of Castelbon, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount of Béarn, and Viscount of Marsan, Gastone I, and his wife, Giovanna d'Artois, as confirmed by the Chronicon Guillelmi de Nangiaco. She was the daughter of Philip d'Artois, son of the Count of Artois, Robert II, and Bianca of Brittany, daughter of the Duke of Brittany and the Count of Richmond, Giovanni II. Bianca's mother was Beatrice of England, daughter of King Henry III of England and his wife, Eleanor of Provence.

Biography

In 1343, his father, Gastone II, entered the service of the King of Castile and León, Alfonso XI, in the crusade against the Sultanate of Granada, and while he was besieging Algeciras (1342-1344) in southern Spain, with King Alfonso XI, he fell ill. He died of the plague in Seville in September 1343; according to the Revue historique, scientifique et littéraire du Tarn, Gastone II was killed fighting in 1344. His body was transported to the County of Foix and buried in the Abbey of Boulbonne. Gastone Febo, the only legitimate son, succeeded him, as per his will drafted on November 28, 1330 (according to the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix, the will was drafted on April 17, 1343, and provided that his wife had custody of the son), while, again according to the Revue historique, scientifique et littéraire du Tarn, the usufruct of the viscountcy of Lautrec went to his wife, Leonora.

Gastone Febo succeeded his father at the age of twelve, and his mother, Eleonora, held regency until he reached majority, for about two years; the regency of Leonora is confirmed by document No. XXXVII of the Preuves de l'Histoire générale de Languedoc, volume VII, which attests that Leonora and her son (Alienors de Convenis, countess and viscountess of the county and vice-county of the aforementioned, and all his said Lord's minor children), in 1344, received homage from the nobles and dignitaries of the County of Foix.

In document No. XXXVI of the Documents des archives de la Chambre des Comptes de Navarre: 1196-1384, dated February 8, 1347, the King of France, Philip VI of Valois, committed to renouncing rights over the lands he would cede to Agnes of Navarre or Évreux (Agnes, daughter... of Phelippe, former king, and... Jehnne of France, queen of Navarre) when she married Gaston Phoebus (Gaston, Count of Foix... [son of] Eleanor of Comminges, Countess of Foix).

Given the geographical position of his two domains, Gastone found himself as a vassal of the Duke of Gascony and King of England, Edward III, for the viscounty of Béarn, and as a vassal of the King of France, Philip VI of Valois, for the County of Foix. Since the two sovereigns sought to draw him into their orbit, Gastone Febo managed to remain sufficiently neutral (in 1347, he declared that Béarn is neutral in the conflict and that he, Gastone Febo, believes that his country belongs to God and his sword), so that when the Hundred Years' War broke out, he was able to keep his fiefs outside the dispute.

In 1349, after the marriage contract was concluded in July 1348, Gastone Febo married Agnese of Navarre, daughter of Queen Joanna II of Navarre (daughter of King Louis X the Quarrelsome of France) and Philip of Évreux, Count of Évreux, son of Louis of Évreux (son of Philip III of France) and Margaret of Artois (descendant of Robert I of Artois, brother of King Louis IX the Saint of France).

Agnese was later repudiated several years after the wedding, in December 1362, shortly after giving birth to her only son, Gastone; to this day, the exact reason remains unknown, but it seems to have been related to the non-payment of the full dowry. Agnese returned to her brother's court, Carlo II the Malvagio (1332–1387), Count of Évreux and King of Navarre.

County of Foix and Viscounty of Béarn

Foix-Béarn

Gastone I

Children

Gastone II

Children

Gastone III

Children

Matteo

Isabella

This box: see • disc. • mod.

Gastone Febo spent his life fighting. He began in 1347 against the English, fighting alongside King Philip VI, then, after being imprisoned in July 1356 by the new King of France, John II the Good, whom he had refused to do homage to for Bearn, he was imprisoned again for being an ally of his brother-in-law, Charles II the Wicked, a fierce enemy of King John II. He was released after the Battle of Poitiers, where John II was captured by the English. Between 1357 and 1358, he went to Prussia, where he fought alongside the Teutonic Knights and Captal de Buch Giovanni III di Grailly against pagan populations. He returned to France in 1358 to fight the Jacquerie. This episode is recounted by historian Alfred Coville: a group of Parisians and other townspeople attacked the market town of Meaux, on an island in the Marne, where the wife of the Dauphin, the Duchess of Normandy, Jeanne of Bourbon, along with several ladies of the court, had taken refuge. They would have been captured if it weren’t for Gastone Febo, who was returning from Prussia and who slaughtered the insurgents.

Then the war resumed for the possession of the viscounty of Béarn (a conflict initiated by great-grandfather Ruggero Bernardo III and continued by grandfather Gastone I and then by father Gastone II) with the Count of Armagnac (an ancient county located between the western part of the Gers department and the eastern part of the Landes department). Gastone Febo managed to defeat and capture, in 1362, at Launac, Count Giovanni I d'Armagnac[1][19][23] (with the ransom he obtained for Giovanni I's release, Gastone Febo, in 1365, became wealthy[19]); the new Count of Armagnac, Giovanni II, then raised further claims on Béarn, and the war resumed in 1375[24]; peace for the viscounty of Béarn was reached in 1378, when an agreement was made for the engagement of Gastone Febo's son, Gastone, with Giovanni II d'Armagnac's daughter, Beatrice d'Armagnac, and their subsequent marriage the following year; the peace treaty is documented in document No. XCI, dated 1348 and 1349, from the Preuves de l'Histoire générale de Languedoc, volume VII[25].

In 1378, the Count of Foix captured some agents of the King of Navarra and brought them before King Charles V of France, who in 1370, then again in 1372 and finally in 1378, had planned the division of the Kingdom of France with the King of England. Additionally, he had organized a plot to poison Charles V, who, without hesitation, ordered the occupation of the Norman territories of the King of Navarra, precisely while Charles the Noble was in Normandy, leading a delegation on behalf of his father that was supposed to negotiate with Charles V. Charles the Noble, who remained a hostage of the King of France, was forced to disown his father.

In 1380, the King of France, Charles V, called the Wise, appointed Gastone Febo as lieutenant for Languedoc, but after Charles V's death, the new king, Charles VI, first called the Beloved and later the Foolish, handed the lieutenantship back to his uncle, the Duke of Berry, Giovanni di Valois, who had previously held it before Gastone Febo.

The French historian Jean Froissart, a contemporary of Gastone Febo, described the events that, in 1381, led to the death of his son, Gastone. Incited by his uncle, the King of Navarre, Carlo II the Malicious, he had attempted to poison him; Gastone Febo, after feeling the urge to kill his son, decided to imprison him with the intention of freeing him after a few weeks. However, when he learned that his son refused to eat the food he sent, he rushed into the cell, had an argument with him, and pointed a knife at his throat. He then returned to his chambers. Unfortunately, the knife had lacerated a vein in the neck, and consequently, Gastone died. It was an accident.

In 1390, Gastone Febo received, with great magnificence, the King Charles VI in the county of Foix, who granted him a lifelong annuity on the county of Bigorre, while Gastone Febo named the king as his heir, as also confirmed by the Histoire générale de Languedoc begun by Gabriel Marchand.

Gastone Febo died of a stroke, in August 1391, at Sauveterre-de-Béarn, near Orthez, during a bear hunt, while he was washing his hands for lunch. He was buried in the church of the Dominicans, known as the Giacobini of Orthez.

Although he had nominated the king as his successor, Gastone Febo was succeeded by a cousin, Matteo di Foix-Béarn, from the cadet branch of Foix-Castelbon.

Essayist and musician

Gastone Febo is considered one of the greatest hunters of his time, and between 1387 and 1389, he wrote a book in French about hunting, the Livre de chasse, regarded as one of the best medieval treatises that covered hunting methods and techniques, and also discussed the breeds of dogs most suitable for hunting operations.

Furthermore, also in French, compose a prayer book, 'Livre des oraisons'; it is a widespread opinion that it was written after the incident involving the son.

Finally, Gastone Febo was a connoisseur and lover of music who also left us some musical compositions. Among other things, he is credited with the authorship of a song from the Pyrenean regions, 'Se canta,' which today is the anthem of the Occitan people.

Lineage

Gastone Febo and Agnese had a single child[1][18][33]:

Gastone (1362-1381), killed accidentally by his father[27]

Gastone Febo had four children from different lovers, whose names and origins are unknown.

Garcia, Viscount of Ossau, cited both by Froissart and Père Anselme.

Peranudet, a young man who died young, cited by Père Anselme.

Bernal de Foix, who died around 1383, and who, according to Père Anselme (1625-1694), was the first Count of Medinaceli through marriage to Isabella de la Cerda Pérez de Guzmán.

Giovanni, called Yvairt, died on January 30, 1392, cited by Froissart. According to Père Anselme, he was destined to succeed his father by the latter's will. Père Anselme recalls his death: he was burned alive during a dance party for Charles VI, when his clothes accidentally caught fire.

Gace de La Bigne [Note 1] was a Norman poet of the 14th century, and served as a master chaplain at the court of the kings of France from 1348 [1].

Biography

Childhood and family

Gace de la Bigne was born in the village of La Bigne, in the deanery of Villers-Bocage. He was born around 1310.

He probably belonged to the family of the lords of La Bigne in the diocese of Bayeux. He came from a noble family of Lower Normandy, whose fiefs were called La Buigne, Aignaulx, Clunchamp, and Buron. These villages are now located in the Calvados department. According to his own account of his life in his poem, he learned the art of falconry from a young age, a passion inherited from his ancestors. He learned to hunt very early; his family took him out when he was nine years old.

And also that deduced from the birds.

He made him wear the armor.

And he led him through the fields.

Who was only nine years old.

about twelve years

He had a falcon pointed at him.

Priest and first chaplain to the King of France

He began his studies at the Collège d'Harcourt in Paris. His family was, in fact, related to the founders. Once he completed his studies, thanks to family ties and friendships formed during his stay in Paris, he was ordained a priest by Cardinal Bishop of Preneste, Pierre des Prés [ CG 3 ]. He was assigned to the parish of La Goulafrière in the Eure department. Subsequently, Pope Benedict XII granted him the canonry at Saint-Pierre de Gerberoi, on the recommendation of Pierre des Prés [ 3 ], [ Note 3 ].

When he became the chaplain of the latter, he obtained various benefits from the Holy See and accompanied him to Avignon. When Gace left his protector, he had high income, had been able to associate with a large number of scholars, learned men, and artists, and had risen in the hierarchy of ecclesiastical benefices [ GH 2 ].

He later became the first chaplain ('master chaplain') to three kings of France, which made him both an ecclesiastic and a courtier. He remained in charge of the Royal Chapel for over thirty years, from 1348 to 1384 [GH 3]. In fact, archival documents confirm that he died in 1384 [GH 4].

He entered the service of the Chapel of the King under Philip VI. The start of his service is now known to us thanks to an archival document indicating the date September 14, 1349, in his role ('Gassio de la Buigne, chaplain of the said lord [king]'). From 1350, he was granted the title of 'prior capellanus domini regis,' which could mean he obtained the dignity of chief chaplain, perhaps replacing Denis Le Grand, who was appointed Bishop of Senlis on the same date [GH 5].

He continued in this role until his death, during the reigns of Giovanni II and Carlo V. As First Chaplain of the King, Gace de La Bigne received a salary of one gold franc per day. Several archival documents, preserved in the Royal Treasury, the Papal Curia, and the Parliament of Paris, record his duties, as well as the benefits and gratuities he received.

To Giovanni, after decreeing the founding of a collegiate church at Saint-Ouen, near Paris, he assigned the position of treasurer to Gace de La Bigne and granted him in advance the use of the land of Lingèvres in the canton of Balleroy, which he intended to endow with this office. But since this king died before the founding was completed, Charles V, his son, claimed the land of Lingèvres and, in compensation, granted Gace de La Bigne a pension of two hundred gold francs to be drawn from the revenues of the viscounty of Bayeux [ GLR 3 ].

Imprisonment in England in the company of the King of France.

Captured in the Battle of Poitiers, Giovanni II, known as 'Giovanni the Good,' brought his first chaplain with him. Gace de La Bigne accompanied him during his imprisonment at Hereford Castle and later at Somerton Castle. Due to the failure of negotiations between Edward III and the imprisoned king, sanctions were imposed on Giovanni the Good, including the dismissal of thirty-five members of his entourage. It was at this point that Gace de la Bigne returned to France with a safe-conduct after a four-month stay in Hertford.

The king, who was a hunting enthusiast and had not yet been released from prison, commissioned Gace in 1359 to compose a work on hunting for his four-year-old son, Philippe, described as capable of infusing aristocratic elegance [2], [GLR 1].

Author of a hunting treatise for the son of the King of France.

Opening of the Dedotto Novel

Gace de la Bigne is the author of a treatise on hunting, at the request of the King of France, titled: Roman des deduis, which began around 1360 and was probably completed between 1373 and 1377 [ GH 8 ].

He began this long work in England, which he completed in France after the death of King John, around 1377 [1].

The work is dedicated to Filippo II l'Ardito, son of the king who commissioned it and future duke of Burgundy [5].

Relationships

The chancellor of the Chancellery, Eustache de Morsant, who died on September 5, 1373, had appointed Gace de la Bigne as his testamentary executor. This means that Gace maintained relationships with officials of the Chancellery and Parliament. These relationships attest to a significant intellectual life at the Palazzo della Cancelleria, which would flourish during the 15th century. Therefore, Gace de la Bigne's life allows us to better understand the relationships between contemporary writers and the existence of cultural centers within the parliamentary and ecclesiastical environments of the Middle Ages [ GH 9 ].

Dead

According to the documents preserved in the archives of the Parliament of Paris, as well as in the documents left by his executors, it can be stated that Gace de la Bigne died in the year 1384 [ GH 4 ].

The novel of the deduced

A treatise on the art of hunting

The book was written with the intent of being a treatise on falconry and hunting, a didactic manual commissioned by the King of France and dedicated to his son. However, the didactic style is that of the Middle Ages, in the sense that the skills explained are presented allegorically. The work takes the form of a legal argument. The author draws inspiration from the books of Burgundian literature [6].

Composition

The novel is written in verse. The work is divided into two parts. The first part is an allegorical discourse that uses the art of falconry to draw moral lessons, to expose virtues and vices. The second part is a debate between the Love of Birds and the Love of Dogs, two supporters of their respective causes, advocating for falconry and hunting respectively. The truth helps to establish a balance by arbitrating the debate.

In this poem, he reveals that he has received a love for hunting since childhood, when he was taken hunting from the age of nine. He also provides personal information regarding his ancient and noble lineage, from both his father's and mother's sides [ GLR 1 ].

The poet was born in Normandy.

From all four sides of the line

Many have loved birds.

From those of Bigne and Aigneaux

And from Clinchamp and Buron.

It is the priest we are talking about.

If no one should be surprised

If birds are very expensive.

When it is so inclined.

Naturally, from all parts.

Why things can often be generated

They produce similar things.

also adds information regarding his role with the kings of France [ CG 4 ]

Why did he serve three kings of France?

In their sovereign chapel

Of the three, the master chaplain.

Various editions

The Romance of the Deduced has been republished multiple times.

The original edition is held at the National Library of France in the Manuscripts Department: Gace de la Bigne, Le Romant des Deduis (manuscript - Parchment, miniature - Shelf mark: Français 1615), dating from 1401 to 1500 (read online [archive]).

First reprint: Phebus, from the deductions of the hunting of wild beasts and birds of prey: Followed by the Poem of Gace de la Bigne on hunting, Antoine Vérard, 1507 (BNF 30485679, read online [archive]) The 'read online' link directly leads to Gace de la Bigne's poem at the end.

Second edition: Phebus des Deduitz de la chasse des bestes sauvages et des oyseaulx de proye: Poem on bird hunting and the chase, Jean Trepperel, between 1507 and 1511 (BNF 30472702)

Contemporary reprint: Gace de la Buigne and Åke Blomqvist (scientific editor), Le Roman des deduis, critical edition based on all manuscripts, Karlshamn, EG Johanssons Boktryck, 1951 (BNF 31827310)

The poetry was subsequently removed during the reissues.

The first curator, Antoine Verard, placed Gaston Fébus's work titled Livre de chasse, on the deductions of hunting wild beasts, at the beginning of the volume, before that of Gace de La Bigne [7]. Then, to make it easier to attribute both works along with the first, he removed the verses cited above, in which La Bigne reveals his origins, and all those containing details about various circumstances of his life [GLR 4].

The second edition of Jean Treperel and the third of Philippe-le-Noir are copies of the one modified by Antoine Vérard. While some biographers, out of ignorance, have changed the author's name on these editions, publishers, on the other hand, deliberately omitted it at the time of publishing his work [GLR 5]. In fact, the publisher Antoine Vérard aimed to increase sales by including a famous name on the cover, as in the case of Gaston Phoebus, known for his pack of 1,600 dogs [CG 5].

Heraldry

According to his seal, which appears at the bottom of a receipt, he heralded: a band charged with a star and accompanied by three bisants or torteaux [CG 6].

Book of the Hunt by Gaston Febus. 1387-1389. National Library of France, Paris (Francais 616). Publisher Moleiro, 2017. Leather binding enriched with gold and blind embossing, in a leather case. 436 pages. 87 miniatures. Edition of 987 copies (ours no. 488). In excellent condition. Some minimal, negligible scuffing at the corners.

The Book of Hunting was written between 1387 and 1389. More precisely, it was dictated to a scribe by Gaston Fébus, Count of Foix and Viscount of Béarn, and dedicated to the Duke of Burgundy, Philip II the Bold. A man of complex personality and tumultuous life, Fébus was not only a great hunter but also a passionate lover of books on hunting and falconry. The volume he carefully composed became the reference work for all enthusiasts of the art of hunting until the end of the 16th century.

Of the 44 preserved copies, the French manuscript 616 is undoubtedly the most beautiful and complete. In addition to the actual Book of the Hunt, this manuscript also contains the Book of Prayers, also written by Gaston Fébus, as well as a second treatise called 'Déduits de la chasse' ('Pleasures of the Hunt') authored by Gace de la Buigne.

To illustrate its pages, there are 87 miniatures of extraordinary quality, which are among the most fascinating productions of Parisian miniatures from the early 15th century. Furthermore, there are certainly not many books dedicated to the art of hunting with a pictorial richness comparable to that of Bibles.

The teachings

The Book of Hunting was until the end of the 16th century the 'breviary' of hunting and game management followers. It is a manual of instructions for hunters, structured into seven chapters with a prologue and an epilogue, which describes in detail how to carry out a hunt. Written for young apprentices, the text offers concise teachings but presents them with the liveliness of someone passionate about the subject. Gaston Fébus does not forget the importance of the animals involved in hunting, especially dogs, faithful companions of hunters. He shares his knowledge about different breeds and their respective behaviors, training, feeding, and even how to treat various illnesses. It is evident that hunting, the passion par excellence of medieval lords, is not just a pastime, as it requires many skills and qualities both human and professional.

However, focusing solely on the technical content would be like overlooking the essence of Gaston Fébus's work. Beyond the realm of hunting, this personal and original treatise is primarily a product of its time, when the idea of sin and the fear of condemnation were omnipresent. In composing the work, Gaston Fébus presents hunting as an exercise in redemption that would grant the hunter direct access to Paradise. In fact, the physical activity of hunting, which already requires a certain level of skill, is an excellent antidote to idleness, the root of all evil. At the same time, it trains body and mind in prudence, thus avoiding any possibility of sin. What this work reveals is nothing other than the tragedy of human existence, the quest for eternal life after passing through the earthly world, which is ultimately where we earn it.

The Illustration

The miniatures of the Book of Chess were commissioned from various artists, including a group known as 'corrente Bedford.' Among them stands out the Master of the Adelfi for his sense of observation and decorative stylization, which make his works the most representative examples of the international Gothic style. Associated with this group is also the Master of Egerton, whose style is close to that of the Limbourg brothers. Finally, we believe we can also recognize in him the Master of the Othea Epistle, whose works are characterized by a thicker stroke, different from the delicate craftsmanship typical of the 'corrente Bedford,' with which he seems to have collaborated only on this manuscript.

Mastering the codes of representation of the Middle Ages perfectly, the miniaturists put their art at the service of Gaston Fébus's pedagogical project. The backgrounds are elegantly decorated with miniatures that, in a reduced format, resemble the tapestries of the era. The aim is not to depict a real space, but rather to rely on a hierarchy of values. Everything is cast and reproduced in a coherent discourse. The passage of time is well evoked by the age of the characters, their activities, their relationships, and their position in space: thus creating a parallel between hunting and the process of learning about life. The mimetic yet orderly character of the elements gives the whole a broad scope and a certain air of serenity, guiding the reader through the secrets of a hunting conducted with masterful skill. More than a lesson in hunting, it is a lesson in life.

History of the Code

Throughout its history, the manuscript changed owners numerous times. It first belonged to Aymar de Poitiers (late 15th century) and then to Bernando Cles, bishop of Trento, who shortly before 1530 gifted it to Ferdinand I of Austria, a prince of Spain and archduke of Austria, brother of Charles V. In 1661, the Marquis of Vigneau also gifted the Book of the Hunt to King Louis XIV (reigned 1643-1715), who ordered it to be kept in the Royal Library. In 1709, it was removed from the library and came into the hands of the heir to France, the Duke of Burgundy, who stored it in the Cabinet du Roi. In 1726, the manuscript reappeared in the library of the Château of Rambouillet, owned by Louis XIV’s illegitimate son, Louis Alexander of Bourbon. After his death, it was inherited by his son, the Duke of Penthièvre. Later, it belonged to the Orleans family and finally to King Louis-Philippe, who in 1834 brought it to the Louvre. After the 1848 revolution, it was returned to the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gastone di Foix, known as Febo (in Catalan: Gastó III de Foix, in Castilian: Gastón III Febus, in Occitan: Gaston II de Fois-Bearn, and in French: Gaston III de Foix-Béarn; Orthez, April 30, 1331 – Sauveterre-de-Béarn, August 1, 1391), was an important feudal lord of Gascony and Languedoc. He was Count of Foix, Viscount of Béarn, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount of Marsan, and Viscount of Lautrec from 1343 until his death.

Gastone received the nickname of Phoebus, both for his beauty, his love for art, and also because he had the sun as an emblem.

Family background

Gastone Febo, according to Pierre de Guibours, also known as Père Anselme de Sainte-Marie or more briefly Père Anselme, and according to the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix was the eldest legitimate son of the Count of Foix, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount consort of Béarn, Viscount of Marsan, and Viscount of Lautrec, Gastone II, and his wife, Leonora of Cominges, who was the daughter of Count Bernardo VII of Cominges and Laura of Monfort, as evidenced by the extract from the Mars MCCCXCVI of the Histoire généalogique de la maison d'Auvergne.

Gastone II of Foix-Béarn, according to both Père Anselme and the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix, was the eldest son of the Count of Foix, Viscount of Castelbon, Co-Prince of Andorra, Viscount of Béarn, and Viscount of Marsan, Gastone I, and his wife, Giovanna d'Artois, as confirmed by the Chronicon Guillelmi de Nangiaco. She was the daughter of Philip d'Artois, son of the Count of Artois, Robert II, and Bianca of Brittany, daughter of the Duke of Brittany and the Count of Richmond, Giovanni II. Bianca's mother was Beatrice of England, daughter of King Henry III of England and his wife, Eleanor of Provence.

Biography

In 1343, his father, Gastone II, entered the service of the King of Castile and León, Alfonso XI, in the crusade against the Sultanate of Granada, and while he was besieging Algeciras (1342-1344) in southern Spain, with King Alfonso XI, he fell ill. He died of the plague in Seville in September 1343; according to the Revue historique, scientifique et littéraire du Tarn, Gastone II was killed fighting in 1344. His body was transported to the County of Foix and buried in the Abbey of Boulbonne. Gastone Febo, the only legitimate son, succeeded him, as per his will drafted on November 28, 1330 (according to the Chroniques romanes des comtes de Foix, the will was drafted on April 17, 1343, and provided that his wife had custody of the son), while, again according to the Revue historique, scientifique et littéraire du Tarn, the usufruct of the viscountcy of Lautrec went to his wife, Leonora.

Gastone Febo succeeded his father at the age of twelve, and his mother, Eleonora, held regency until he reached majority, for about two years; the regency of Leonora is confirmed by document No. XXXVII of the Preuves de l'Histoire générale de Languedoc, volume VII, which attests that Leonora and her son (Alienors de Convenis, countess and viscountess of the county and vice-county of the aforementioned, and all his said Lord's minor children), in 1344, received homage from the nobles and dignitaries of the County of Foix.

In document No. XXXVI of the Documents des archives de la Chambre des Comptes de Navarre: 1196-1384, dated February 8, 1347, the King of France, Philip VI of Valois, committed to renouncing rights over the lands he would cede to Agnes of Navarre or Évreux (Agnes, daughter... of Phelippe, former king, and... Jehnne of France, queen of Navarre) when she married Gaston Phoebus (Gaston, Count of Foix... [son of] Eleanor of Comminges, Countess of Foix).

Given the geographical position of his two domains, Gastone found himself as a vassal of the Duke of Gascony and King of England, Edward III, for the viscounty of Béarn, and as a vassal of the King of France, Philip VI of Valois, for the County of Foix. Since the two sovereigns sought to draw him into their orbit, Gastone Febo managed to remain sufficiently neutral (in 1347, he declared that Béarn is neutral in the conflict and that he, Gastone Febo, believes that his country belongs to God and his sword), so that when the Hundred Years' War broke out, he was able to keep his fiefs outside the dispute.

In 1349, after the marriage contract was concluded in July 1348, Gastone Febo married Agnese of Navarre, daughter of Queen Joanna II of Navarre (daughter of King Louis X the Quarrelsome of France) and Philip of Évreux, Count of Évreux, son of Louis of Évreux (son of Philip III of France) and Margaret of Artois (descendant of Robert I of Artois, brother of King Louis IX the Saint of France).

Agnese was later repudiated several years after the wedding, in December 1362, shortly after giving birth to her only son, Gastone; to this day, the exact reason remains unknown, but it seems to have been related to the non-payment of the full dowry. Agnese returned to her brother's court, Carlo II the Malvagio (1332–1387), Count of Évreux and King of Navarre.

County of Foix and Viscounty of Béarn

Foix-Béarn

Gastone I

Children

Gastone II

Children

Gastone III

Children

Matteo

Isabella

This box: see • disc. • mod.

Gastone Febo spent his life fighting. He began in 1347 against the English, fighting alongside King Philip VI, then, after being imprisoned in July 1356 by the new King of France, John II the Good, whom he had refused to do homage to for Bearn, he was imprisoned again for being an ally of his brother-in-law, Charles II the Wicked, a fierce enemy of King John II. He was released after the Battle of Poitiers, where John II was captured by the English. Between 1357 and 1358, he went to Prussia, where he fought alongside the Teutonic Knights and Captal de Buch Giovanni III di Grailly against pagan populations. He returned to France in 1358 to fight the Jacquerie. This episode is recounted by historian Alfred Coville: a group of Parisians and other townspeople attacked the market town of Meaux, on an island in the Marne, where the wife of the Dauphin, the Duchess of Normandy, Jeanne of Bourbon, along with several ladies of the court, had taken refuge. They would have been captured if it weren’t for Gastone Febo, who was returning from Prussia and who slaughtered the insurgents.

Then the war resumed for the possession of the viscounty of Béarn (a conflict initiated by great-grandfather Ruggero Bernardo III and continued by grandfather Gastone I and then by father Gastone II) with the Count of Armagnac (an ancient county located between the western part of the Gers department and the eastern part of the Landes department). Gastone Febo managed to defeat and capture, in 1362, at Launac, Count Giovanni I d'Armagnac[1][19][23] (with the ransom he obtained for Giovanni I's release, Gastone Febo, in 1365, became wealthy[19]); the new Count of Armagnac, Giovanni II, then raised further claims on Béarn, and the war resumed in 1375[24]; peace for the viscounty of Béarn was reached in 1378, when an agreement was made for the engagement of Gastone Febo's son, Gastone, with Giovanni II d'Armagnac's daughter, Beatrice d'Armagnac, and their subsequent marriage the following year; the peace treaty is documented in document No. XCI, dated 1348 and 1349, from the Preuves de l'Histoire générale de Languedoc, volume VII[25].

In 1378, the Count of Foix captured some agents of the King of Navarra and brought them before King Charles V of France, who in 1370, then again in 1372 and finally in 1378, had planned the division of the Kingdom of France with the King of England. Additionally, he had organized a plot to poison Charles V, who, without hesitation, ordered the occupation of the Norman territories of the King of Navarra, precisely while Charles the Noble was in Normandy, leading a delegation on behalf of his father that was supposed to negotiate with Charles V. Charles the Noble, who remained a hostage of the King of France, was forced to disown his father.

In 1380, the King of France, Charles V, called the Wise, appointed Gastone Febo as lieutenant for Languedoc, but after Charles V's death, the new king, Charles VI, first called the Beloved and later the Foolish, handed the lieutenantship back to his uncle, the Duke of Berry, Giovanni di Valois, who had previously held it before Gastone Febo.

The French historian Jean Froissart, a contemporary of Gastone Febo, described the events that, in 1381, led to the death of his son, Gastone. Incited by his uncle, the King of Navarre, Carlo II the Malicious, he had attempted to poison him; Gastone Febo, after feeling the urge to kill his son, decided to imprison him with the intention of freeing him after a few weeks. However, when he learned that his son refused to eat the food he sent, he rushed into the cell, had an argument with him, and pointed a knife at his throat. He then returned to his chambers. Unfortunately, the knife had lacerated a vein in the neck, and consequently, Gastone died. It was an accident.

In 1390, Gastone Febo received, with great magnificence, the King Charles VI in the county of Foix, who granted him a lifelong annuity on the county of Bigorre, while Gastone Febo named the king as his heir, as also confirmed by the Histoire générale de Languedoc begun by Gabriel Marchand.

Gastone Febo died of a stroke, in August 1391, at Sauveterre-de-Béarn, near Orthez, during a bear hunt, while he was washing his hands for lunch. He was buried in the church of the Dominicans, known as the Giacobini of Orthez.

Although he had nominated the king as his successor, Gastone Febo was succeeded by a cousin, Matteo di Foix-Béarn, from the cadet branch of Foix-Castelbon.

Essayist and musician

Gastone Febo is considered one of the greatest hunters of his time, and between 1387 and 1389, he wrote a book in French about hunting, the Livre de chasse, regarded as one of the best medieval treatises that covered hunting methods and techniques, and also discussed the breeds of dogs most suitable for hunting operations.

Furthermore, also in French, compose a prayer book, 'Livre des oraisons'; it is a widespread opinion that it was written after the incident involving the son.

Finally, Gastone Febo was a connoisseur and lover of music who also left us some musical compositions. Among other things, he is credited with the authorship of a song from the Pyrenean regions, 'Se canta,' which today is the anthem of the Occitan people.

Lineage

Gastone Febo and Agnese had a single child[1][18][33]:

Gastone (1362-1381), killed accidentally by his father[27]

Gastone Febo had four children from different lovers, whose names and origins are unknown.

Garcia, Viscount of Ossau, cited both by Froissart and Père Anselme.

Peranudet, a young man who died young, cited by Père Anselme.

Bernal de Foix, who died around 1383, and who, according to Père Anselme (1625-1694), was the first Count of Medinaceli through marriage to Isabella de la Cerda Pérez de Guzmán.

Giovanni, called Yvairt, died on January 30, 1392, cited by Froissart. According to Père Anselme, he was destined to succeed his father by the latter's will. Père Anselme recalls his death: he was burned alive during a dance party for Charles VI, when his clothes accidentally caught fire.

Gace de La Bigne [Note 1] was a Norman poet of the 14th century, and served as a master chaplain at the court of the kings of France from 1348 [1].

Biography

Childhood and family

Gace de la Bigne was born in the village of La Bigne, in the deanery of Villers-Bocage. He was born around 1310.

He probably belonged to the family of the lords of La Bigne in the diocese of Bayeux. He came from a noble family of Lower Normandy, whose fiefs were called La Buigne, Aignaulx, Clunchamp, and Buron. These villages are now located in the Calvados department. According to his own account of his life in his poem, he learned the art of falconry from a young age, a passion inherited from his ancestors. He learned to hunt very early; his family took him out when he was nine years old.

And also that deduced from the birds.

He made him wear the armor.

And he led him through the fields.

Who was only nine years old.

about twelve years

He had a falcon pointed at him.

Priest and first chaplain to the King of France

He began his studies at the Collège d'Harcourt in Paris. His family was, in fact, related to the founders. Once he completed his studies, thanks to family ties and friendships formed during his stay in Paris, he was ordained a priest by Cardinal Bishop of Preneste, Pierre des Prés [ CG 3 ]. He was assigned to the parish of La Goulafrière in the Eure department. Subsequently, Pope Benedict XII granted him the canonry at Saint-Pierre de Gerberoi, on the recommendation of Pierre des Prés [ 3 ], [ Note 3 ].

When he became the chaplain of the latter, he obtained various benefits from the Holy See and accompanied him to Avignon. When Gace left his protector, he had high income, had been able to associate with a large number of scholars, learned men, and artists, and had risen in the hierarchy of ecclesiastical benefices [ GH 2 ].

He later became the first chaplain ('master chaplain') to three kings of France, which made him both an ecclesiastic and a courtier. He remained in charge of the Royal Chapel for over thirty years, from 1348 to 1384 [GH 3]. In fact, archival documents confirm that he died in 1384 [GH 4].

He entered the service of the Chapel of the King under Philip VI. The start of his service is now known to us thanks to an archival document indicating the date September 14, 1349, in his role ('Gassio de la Buigne, chaplain of the said lord [king]'). From 1350, he was granted the title of 'prior capellanus domini regis,' which could mean he obtained the dignity of chief chaplain, perhaps replacing Denis Le Grand, who was appointed Bishop of Senlis on the same date [GH 5].

He continued in this role until his death, during the reigns of Giovanni II and Carlo V. As First Chaplain of the King, Gace de La Bigne received a salary of one gold franc per day. Several archival documents, preserved in the Royal Treasury, the Papal Curia, and the Parliament of Paris, record his duties, as well as the benefits and gratuities he received.

To Giovanni, after decreeing the founding of a collegiate church at Saint-Ouen, near Paris, he assigned the position of treasurer to Gace de La Bigne and granted him in advance the use of the land of Lingèvres in the canton of Balleroy, which he intended to endow with this office. But since this king died before the founding was completed, Charles V, his son, claimed the land of Lingèvres and, in compensation, granted Gace de La Bigne a pension of two hundred gold francs to be drawn from the revenues of the viscounty of Bayeux [ GLR 3 ].

Imprisonment in England in the company of the King of France.

Captured in the Battle of Poitiers, Giovanni II, known as 'Giovanni the Good,' brought his first chaplain with him. Gace de La Bigne accompanied him during his imprisonment at Hereford Castle and later at Somerton Castle. Due to the failure of negotiations between Edward III and the imprisoned king, sanctions were imposed on Giovanni the Good, including the dismissal of thirty-five members of his entourage. It was at this point that Gace de la Bigne returned to France with a safe-conduct after a four-month stay in Hertford.

The king, who was a hunting enthusiast and had not yet been released from prison, commissioned Gace in 1359 to compose a work on hunting for his four-year-old son, Philippe, described as capable of infusing aristocratic elegance [2], [GLR 1].

Author of a hunting treatise for the son of the King of France.

Opening of the Dedotto Novel

Gace de la Bigne is the author of a treatise on hunting, at the request of the King of France, titled: Roman des deduis, which began around 1360 and was probably completed between 1373 and 1377 [ GH 8 ].

He began this long work in England, which he completed in France after the death of King John, around 1377 [1].

The work is dedicated to Filippo II l'Ardito, son of the king who commissioned it and future duke of Burgundy [5].

Relationships

The chancellor of the Chancellery, Eustache de Morsant, who died on September 5, 1373, had appointed Gace de la Bigne as his testamentary executor. This means that Gace maintained relationships with officials of the Chancellery and Parliament. These relationships attest to a significant intellectual life at the Palazzo della Cancelleria, which would flourish during the 15th century. Therefore, Gace de la Bigne's life allows us to better understand the relationships between contemporary writers and the existence of cultural centers within the parliamentary and ecclesiastical environments of the Middle Ages [ GH 9 ].

Dead

According to the documents preserved in the archives of the Parliament of Paris, as well as in the documents left by his executors, it can be stated that Gace de la Bigne died in the year 1384 [ GH 4 ].

The novel of the deduced

A treatise on the art of hunting

The book was written with the intent of being a treatise on falconry and hunting, a didactic manual commissioned by the King of France and dedicated to his son. However, the didactic style is that of the Middle Ages, in the sense that the skills explained are presented allegorically. The work takes the form of a legal argument. The author draws inspiration from the books of Burgundian literature [6].

Composition

The novel is written in verse. The work is divided into two parts. The first part is an allegorical discourse that uses the art of falconry to draw moral lessons, to expose virtues and vices. The second part is a debate between the Love of Birds and the Love of Dogs, two supporters of their respective causes, advocating for falconry and hunting respectively. The truth helps to establish a balance by arbitrating the debate.

In this poem, he reveals that he has received a love for hunting since childhood, when he was taken hunting from the age of nine. He also provides personal information regarding his ancient and noble lineage, from both his father's and mother's sides [ GLR 1 ].

The poet was born in Normandy.

From all four sides of the line

Many have loved birds.

From those of Bigne and Aigneaux

And from Clinchamp and Buron.

It is the priest we are talking about.

If no one should be surprised

If birds are very expensive.

When it is so inclined.

Naturally, from all parts.

Why things can often be generated

They produce similar things.

also adds information regarding his role with the kings of France [ CG 4 ]

Why did he serve three kings of France?

In their sovereign chapel

Of the three, the master chaplain.

Various editions

The Romance of the Deduced has been republished multiple times.

The original edition is held at the National Library of France in the Manuscripts Department: Gace de la Bigne, Le Romant des Deduis (manuscript - Parchment, miniature - Shelf mark: Français 1615), dating from 1401 to 1500 (read online [archive]).

First reprint: Phebus, from the deductions of the hunting of wild beasts and birds of prey: Followed by the Poem of Gace de la Bigne on hunting, Antoine Vérard, 1507 (BNF 30485679, read online [archive]) The 'read online' link directly leads to Gace de la Bigne's poem at the end.

Second edition: Phebus des Deduitz de la chasse des bestes sauvages et des oyseaulx de proye: Poem on bird hunting and the chase, Jean Trepperel, between 1507 and 1511 (BNF 30472702)

Contemporary reprint: Gace de la Buigne and Åke Blomqvist (scientific editor), Le Roman des deduis, critical edition based on all manuscripts, Karlshamn, EG Johanssons Boktryck, 1951 (BNF 31827310)

The poetry was subsequently removed during the reissues.

The first curator, Antoine Verard, placed Gaston Fébus's work titled Livre de chasse, on the deductions of hunting wild beasts, at the beginning of the volume, before that of Gace de La Bigne [7]. Then, to make it easier to attribute both works along with the first, he removed the verses cited above, in which La Bigne reveals his origins, and all those containing details about various circumstances of his life [GLR 4].

The second edition of Jean Treperel and the third of Philippe-le-Noir are copies of the one modified by Antoine Vérard. While some biographers, out of ignorance, have changed the author's name on these editions, publishers, on the other hand, deliberately omitted it at the time of publishing his work [GLR 5]. In fact, the publisher Antoine Vérard aimed to increase sales by including a famous name on the cover, as in the case of Gaston Phoebus, known for his pack of 1,600 dogs [CG 5].

Heraldry

According to his seal, which appears at the bottom of a receipt, he heralded: a band charged with a star and accompanied by three bisants or torteaux [CG 6].