. - Il libro delle ore. Codice Rossiano 94 - 1500-1984

Add to your favourites to get an alert when the auction starts.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 123418 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

Description from the seller

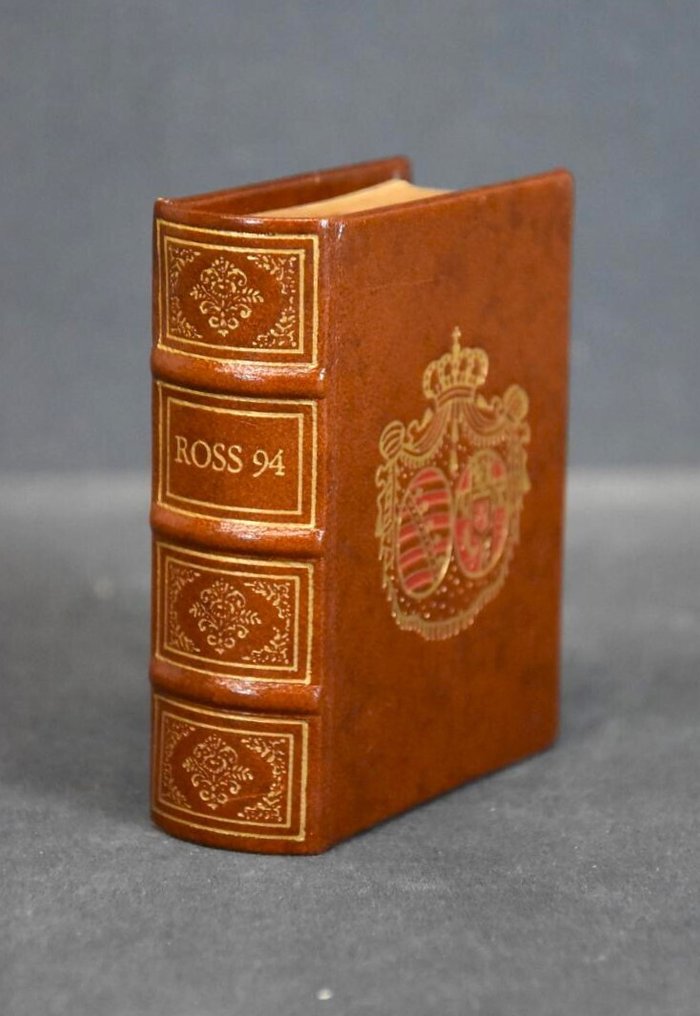

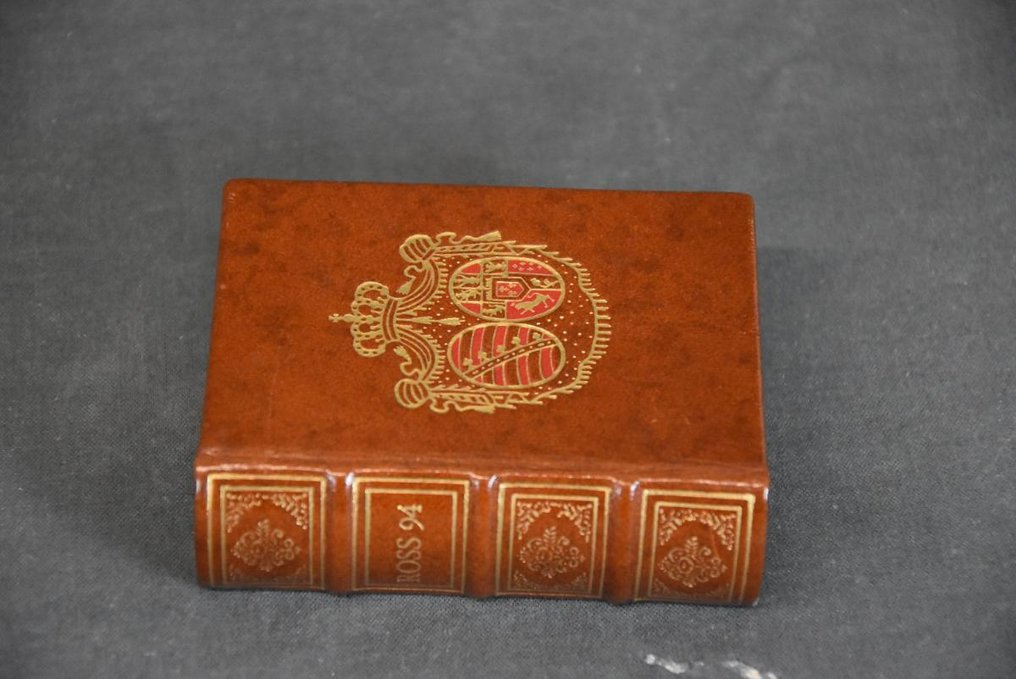

Rossiano Code 94. Jaca Book, 1984. Leather binding, gold embellishments and title. In excellent condition. Preserved in a cloth case. In excellent condition - slight stains on the case.

The Rossiano Codex 94 (also known as Vatican Rossiano 94) is a famous illuminated manuscript dating from around 1500, currently housed in the Vatican Apostolic Library. It is a Book of Hours, a collection of Christian prayers intended for private devotion, typical of the late medieval and Renaissance periods.

Miniature: It is renowned for its decorative apparatus and high-quality artistic illustrations, typical of the 16th-century miniature school. It was part of the collection of Knight Giovanni Francesco de Rossi (1796-1854). His entire library was donated to the Holy See and, in 1921-1922, was incorporated into the holdings of the Vatican Library.

Modern Editions: In the 1980s (1983-1984), the publishing house Jaca Book published a notable complete facsimile edition (anastatic), accompanied by a commentary by scholar Luigi Michelini Tocci.

Giovanni Francesco Rossi

Giovanni Francesco Rossi (Fivizzano, 17th century – 17th century) was an Italian sculptor. Active in Rome from 1640 to 1677, he collaborated with Ercole Ferrata at Sant'Agnese in Agone and carved reliefs at Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

Luigi Michelini Tocci (Cagli, April 28, 1910 – Rome, February 15, 2000) was an Italian librarian and art historian, specialized in miniatures.

Biography

Claudianus Claudius, Works, Binding

He completed his higher education at the Istituto Massimo in Rome. Appointed director of the Cagli Municipal Library, in 1930 he published a study on a manuscript of the Aeneid kept there. In 1932, with a scholarship, he moved to Hungary. In 1933, he graduated in literature from the University of Rome La Sapienza, with Pietro Paolo Trompeo, defending a thesis on Léon Bloy.

From 1934 to 1944, he was the director of the Oliveriana Library of Pesaro and was involved with the Medal Collection kept in the Civic Museums of Pesaro. During his tenure, the library's headquarters in Palazzo Almerici was restored, and in 1936, the first Marche bibliographic exhibition was organized, for which Luigi Michelini Tocci curated the catalog. In 1936, he organized a preparatory course for staff of public and school libraries, conceived by the Bibliographic Superintendence of Romagna and Marche.

In November 1944, he entered the Vatican Apostolic Library and was assigned to the pontifical medal collection. In 1959, he became responsible for the numismatic cabinet of the same library, and in 1978, head of the 'Art Objects' section owned by the library. A passionate enthusiast of 19th-century literature, Renaissance Italian art, and book history, he published essays on Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, cataloged incunabula, and curated exhibition catalogs in Vatican: Quinto centenario della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1475-1975 (1975), Papal bindings from Eugene IV to Paul VI (1977), Bernini in Vatican (1981). He published monographs on Raphael Sanzio and his era, as well as on ancient artworks and architecture in Pesaro and its surroundings. He contributed to the Enciclopedia dantesca, published by Treccani.

He was entrusted with teaching the History of the Book and Libraries at the Vatican School of Librarianship and with the History of Miniature at the Vatican School of Paleography, Diplomatics, and Archival Science. He was a member of the Italian Librarians Association, for the Lazio section; a member of the Roman Society of Homeland History (since 1973); and of the Pontifical Roman Archaeological Academy, of which he was also secretary from 1971 to 1979.

Writings

Books

(FR, IT) Raffaello's father: Giovanni Santi and some of his most representative works in the Urbino and Pesaro regions, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1961, SBN MOD0376061.

Painters of the 1400s in Urbino and Pesaro, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1965, SBN MOD0299148.

The Roman medallions and the bordered pieces from the Vatican Medal Collection / described by Luigi Michelini Tocci; with an 'Appendix' concerning some silver and bronze laminae and some bronze discs. 2 volumes, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1965, SBN SBL0191781.

Pesaro Sforzesca in the inlays of the choir of S. Agostino, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1971, SBN SBL0378598.

Hermitages and cenobites of Catria, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1972, SBN SBL0436742.

Gradara and the castles on the left of the Foglia, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1974, SBN SBL0571643.

ROSS. 94; The Book of Hours: a commentary volume on the facsimile edition of Cod. ROSS. 94 from the Vatican Apostolic Library, Milan, Jaca Book Codices, 1984, SBN CFI0033780.[5]

(IT, EN) In the workshop of Erasmus: the autograph apparatus of Erasmus for the 1528 edition of the Adagia and a new manuscript of the Compendium vitae, Rome, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1989, SBN LO10028371.

Written in collaboration

Image of Leon Bloy, in Studies on 19th-century literature in honor of Pietro Paolo Trompeo, Naples, Italian Scientific Editions, 1957, SBN VIA0097749.

Printed books belonging to Colocci, in Proceedings of the study conference on Angelo Colocci: Jesi, September 13-14, 1969, Città di Castello, Graphic Arts, 1972, pp. 77-96, SBN SBL0467744.

A pontifical from Cologne to Cagli in the 11th century and some essays on Cagliese writing from the 11th to 12th century, in Palaeographica, diplomatics, and archival science: studies in honor of Giulio Battelli / edited by the Special School for Archivists and Librarians of the University of Rome, vol. 1, Rome, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1979, pp. 265-294, SBN RAV0042417.

Writings for periodicals

Two Urbinati manuscripts of the privileges of Montefeltro, in La Bibliofilia, vol. 60, Florence, L. Olschki, 1959, SBN RAV0006199.

The dedication manuscript of the 'Epistola de vita et gestis Guidubaldi Urbini ducis ad Henricum Angliae regem' by Baldassarre Castiglione, in Medieval and Humanistic Italy, vol. 5, Padua, Antenore, 1962, pp. 273-282, SBN SBL0491729.

Editions

Alexis de Tocqueville, Arthur de Gobineau, Correspondence (1843-1859) / [translation from French] with introduction and notes by Luigi Michelini Tocci, Milan, Longanesi, 1947, SBN CUB0635627.

Augustin Thierry, Tales of the Merovingian Age, Milan, Longanesi, 1949, SBN LO10323661.

The Urbinate Dante of the Vatican Library: Latin Codex Urbinate 365, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1965, SBN SBL0085116.[6]

The Castles of Francesco di Giorgio, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio, 1967, SBN UMC0096649.

Fifth centenary of the Vatican Apostolic Library, 1475-1975: catalog of the exhibition, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1975, SBN SBL0173043.

Papal legatures from Eugenio IV to Paul VI: catalog of the exhibition with 211 plates, of which 35 in color, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1977, SBN BVE0590374.

(DE, IT, LA) Lamberto Donati, Luigi Michelini Tocci (editor), Biblia pauperum: reproduction of the Latin Palatino Codex 143, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1979, SBN SBL0337106.[7]

Luigi Michelini Tocci, Giovanni Morello, Valentino Martinelli, Marc Worsdale (edited by), Lorenzo Bernini, Rome, De Luca, 1981, SBN SBL0346134.

Giovanni Santi, The life and deeds of Federico di Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino: a poem in terza rima: Vat. Ottob. Lat. 1305 codex. 2 volumes, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1985, SBN CFI0014576.[8]

The book of hours (Latin: horæ; French: livres d'heures; Spanish: horas; English: primers) is a popular Christian devotional book from the Middle Ages. It is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like any manuscript, each book of hours is unique but contains a collection of texts similar to others, such as prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often limited to decorated capital letters at the beginning of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons can be extremely sumptuous, with full-page miniatures. These illustrations would combine picturesque scenes of rural life with sacred images. Books of hours were generally written in Latin, although many are entirely or partly in European vernacular languages, particularly Dutch. Tens of thousands of books of hours have survived to this day, in libraries and private collections around the world.

Description

Image of a Book of Hours

A French book of hours from the beginning of the 15th century (MS13, Society of Antiquaries of London) opened to an illustration of the Adoration of the Magi. It was bequeathed to the Society in 1769 by the Rev. Charles Lyttleton, Bishop of Carlisle and President of the Society (1765-1768).

The typical Book of Hours is a shortened form of the breviary, containing the canonical hours recited in monasteries. It was developed for the laity eager to incorporate elements of monastic daily life into their devotional practice. The recitation of the hours typically focused on reading a certain number of psalms and other prayers.

A typical book of hours contains the Calendar of the ecclesiastical feasts (the so-called Liturgical Year), extracts from the Gospel, the readings for Mass for major feasts, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the fifteen Psalms of the Degrees, the seven Penitential Psalms, a Litany of saints, a Office for the dead, and the Hours of the Cross. Most books of hours from the 15th century have these basic contents. Marian prayers Obsecro te ('I beseech you') and O Intemerata ('O Immaculate') were frequently added, as well as devotions to be used during Mass and meditations on the Passion of Jesus among other optional texts.

Story

Example of an affordable book of hours: a 'simple' book of hours in Middle Dutch - second half of the 15th century - Duchy of Brabant.

This level of decoration is also richer than that of most books, although it is less than the sumptuous lighting found in luxury books, which are the ones most often reproduced.

The Book of Hours has its origins in the Psalter used by monks and nuns. By the 12th century, it had developed into the Breviary, with weekly cycles of psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and readings that changed with the liturgical season. Eventually, a selection of texts was produced in much shorter volumes called 'books of hours.' During the latter part of the 13th century, the book of hours became popular as a personal prayer book for men and women leading secular lives. It consisted of a selection of prayers, psalms, hymns, and lessons based on the clergy's liturgy. Each book was unique in its content, although all included the Hours of the Virgin Mary, devotions to be performed during the eight canonical hours of the day, which is the reason behind the name 'Book of Hours'.

Book of Hours by van Reynegom, c. 15th century - Royal Library of Belgium and King Baudouin Foundation.

Many books of hours were created for a female clientele. There is some evidence that they were sometimes given as wedding gifts from the husband to the bride. They were often passed down within families, as shown by wills. Until the 15th century, paper was rare, and most books of hours were made on parchment, paper, or vellum.

Although illuminated books of hours were enormously expensive, a small book with few or no miniatures was easily purchasable, to the extent that it became widely popular in the fifteenth century. The earliest surviving English example was written for a layperson living in Oxford or nearby around 1240: it is smaller than a modern pocket-sized book, well miniated in the initial letters but without full-page miniatures. In the fifteenth century, there are also examples of servants owning their own Libri d'Ore. In a legal case from 1500, a poor woman was accused of stealing a servant's book of hours.

Very rarely did books include prayers composed specifically for their owners, but more often the texts were adapted to their tastes or gender, including the owners' names in the prayers. Some include images depicting the owners and/or their coats of arms. These, along with the choice of saints commemorated in the calendar and the prayers, are the main clues to the identity of the patron. Eamon Duffy explains that 'the personal character of these books has often been indicated by the inclusion of prayers specially composed or adapted for their owners.' Furthermore, he states that 'up to half of the surviving handwritten books of hours contain annotations, marginalia, or additions of some kind. Such additions might not amount to the inclusion of a regional or personal patron saint in the standardized calendar but often include devotional material added by the owner. Owners could write in specific dates important to them, notes about the months in which events they wished to remember occurred, and even the images found within these books would be personalized for the owners, such as localized saints and local festivals.'

At least in the 15th century, Dutch and Parisian workshops produced books of hours for distribution, without waiting for individual commissions. These were sometimes made with spaces left for the addition of personalized elements such as local festivals or heraldry.

Black bulls, Morgan MS 493, Pentecost, folios 18v/19r, circa 1475–80. Morgan Library & Museum, New York

The style and arrangement of traditional Books of Hours became increasingly standardized around the mid-13th century. The new style can be seen in the books produced by the Oxford illuminator William de Brailes, a member of the minor orders who managed a commercial workshop. His books included various aspects of the Breviary and other liturgical elements for lay use. "He incorporated a perpetual calendar, Gospels, prayers to the Virgin Mary, the Way of the Cross, prayers to the Holy Spirit, penitential Psalms, litanies, prayers for the dead, and suffrages to the Saints. The book's goal was to help his devout patroness structure her daily spiritual life according to the eight canonical hours, from Matins to Compline, observed by all devout members of the Church. The text, enriched with rubrics, gilding, miniatures, and beautiful illuminations, aimed to inspire meditation on the mysteries of faith, the sacrifice made by Christ for mankind, and the horrors of hell, while particularly emphasizing devotion to the Virgin Mary, whose popularity peaked during the 13th century." This arrangement persisted over the years as many aristocrats commissioned their own Books of Hours.

By the end of the 15th century, the advent of printing made books more affordable, and much of the emerging middle class could afford to purchase a printed book of hours, with new manuscripts being commissioned only by the wealthiest. The first printed book of hours in Italy dates to 1472 in Venice, by J. Nelson, while production also began in Naples from 1476 (Moravo-Preller). In 1478, W. Caxton produced the first printed book of hours in England at Westminster, while the Netherlands (Brussels and Delft) began printing books of hours in 1480. These were books decorated with woodcuts, initially in limited numbers and increasingly more common.[9] In France, printers instead employed engravers to emulate the miniatures scattered throughout the page typical of handwritten books of hours, then printing on parchment rather than paper and not hesitating to have the drawings hand-colored: e.g., the printed book of hours in 1487 by Antoine Vérard.[10]

The Kitāb ṣalāt al‐sawā'ī (1514), widely considered the first book in Arabic printed with movable type, is a book of hours intended for Arabic-speaking Christians and presumably commissioned by Pope Julius II.

Decoration

A full-page miniature from May, from a calendar cycle by Simon Bening, early 16th century.

Since many Books of Hours are richly illuminated, they serve as important evidence of life in the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as iconography of medieval Christianity. Some of them were also decorated with jeweled covers, portraits, and heraldic emblems. A few were bound as belt books for easy transport, although few of these or other medieval bindings have survived. Luxury books, such as the Talbot Hours of John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, may include a portrait of the owner, and in this case, his wife, kneeling in adoration of the Virgin with Child as a form of donor portrait. In expensive books, miniature cycles depicted the Life of the Virgin or the Passion of Christ in eight scenes that decorate the eight Hours of the Virgin, as well as the Labors of the Months and the zodiac signs that adorn the calendar. Secular scenes in the calendar cycles include many of the most well-known images from Books of Hours and played an important role in the early history of landscape painting.

From the 14th century, decorated borders around the edges of at least important pages were common in heavily illuminated books, including books of hours. At the beginning of the 15th century, these were still usually based on foliage drawings and paintings on a simple background, but in the second half of the century, colored or fantasy backgrounds with images of all kinds of objects were used in luxury books.

Second-hand books of hours were often modified by their new owners, even among royalty. After defeating his rival Riccardo III, Henry VII of England gave his book of hours to his mother, who altered it to include her own name. Heraldry was usually erased or over-painted by new owners. Many contained handwritten annotations, personal additions, and marginal notes, but some new owners also commissioned artisans to add more illustrations or texts. Sir Thomas Lewkenor of Trotton hired an illustrator to add details to what is now known as the Lewkenor Hours. The pastedowns of some surviving books include notes of household accounts or birth and death records, similar to later family Bibles. Some owners also collected autographs of important visitors to their homes. Books of hours were often the only book in a household and were commonly used to teach children to read, sometimes featuring a page with the alphabet to assist them.

Towards the end of the 15th century, printers produced books of hours with woodcut illustrations, and the book of hours was one of the main decorated works using the related metal engraving technique.

The luxury book of hours

The illusionistic boundaries of this Flemish book of hours from the late 15th century are typical of luxury books from this period, which were often decorated on every page. The butterfly wing that cuts across the text area is an example of a play with visual conventions, typical of the era.

Among the plants are Veronica, Vinca, Viola tricolor, Bellis perennis, and Chelidonium majus. The butterfly at the bottom is Aglais urticae, and the butterfly at the top left is Pieris rapae. The Latin text is a devotion to Saint Christopher.

In the 14th century, the book of hours surpassed the psalter as the most common vehicle for luxury miniatures, demonstrating the now established dominance of lay patronage over religious patronage for miniatures. From the late 14th century, a number of crowned bibliophiles began collecting luxurious illuminated manuscripts for their decorations, a fashion that spread throughout Europe from the courts of the Valois in France and Burgundy, as well as in Prague under Charles IV of Luxembourg and later Wenceslaus of Luxembourg. A generation later, Duke Philip III of Burgundy was the most important collector of illuminated manuscripts, and many of his circle were as well. It was during this period that Flemish cities emerged as a driving force in miniature, a position they maintained until the decline of illuminated manuscripts in the early 16th century.

The most famous collector of all, the French prince Giovanni di Valois, Duke of Berry (1340–1416), owned several books of hours, some of which survive, including the most renowned of all, the Très riches heures du Duc de Berry. This work was begun around 1410 by the Limbourg brothers, although left incomplete, and its decoration continued for several decades by other artists and patrons. The same was true for the Hours of Turin, which were also owned, among others, by the Duke of Berry.

By the mid-15th century, a much broader group of nobility and wealthy businessmen was able to commission highly decorated books of hours, often small in size. With the advent of printing, the market sharply contracted, and by 1500, the finest quality books were produced again only for royal or very grand collectors. One of the last great illuminated books of hours was the so-called Farnese Hours of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese the Younger, created in 1546 by Giulio Clovio, the last great manuscript miniaturist.

Rossiano Code 94. Jaca Book, 1984. Leather binding, gold embellishments and title. In excellent condition. Preserved in a cloth case. In excellent condition - slight stains on the case.

The Rossiano Codex 94 (also known as Vatican Rossiano 94) is a famous illuminated manuscript dating from around 1500, currently housed in the Vatican Apostolic Library. It is a Book of Hours, a collection of Christian prayers intended for private devotion, typical of the late medieval and Renaissance periods.

Miniature: It is renowned for its decorative apparatus and high-quality artistic illustrations, typical of the 16th-century miniature school. It was part of the collection of Knight Giovanni Francesco de Rossi (1796-1854). His entire library was donated to the Holy See and, in 1921-1922, was incorporated into the holdings of the Vatican Library.

Modern Editions: In the 1980s (1983-1984), the publishing house Jaca Book published a notable complete facsimile edition (anastatic), accompanied by a commentary by scholar Luigi Michelini Tocci.

Giovanni Francesco Rossi

Giovanni Francesco Rossi (Fivizzano, 17th century – 17th century) was an Italian sculptor. Active in Rome from 1640 to 1677, he collaborated with Ercole Ferrata at Sant'Agnese in Agone and carved reliefs at Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

Luigi Michelini Tocci (Cagli, April 28, 1910 – Rome, February 15, 2000) was an Italian librarian and art historian, specialized in miniatures.

Biography

Claudianus Claudius, Works, Binding

He completed his higher education at the Istituto Massimo in Rome. Appointed director of the Cagli Municipal Library, in 1930 he published a study on a manuscript of the Aeneid kept there. In 1932, with a scholarship, he moved to Hungary. In 1933, he graduated in literature from the University of Rome La Sapienza, with Pietro Paolo Trompeo, defending a thesis on Léon Bloy.

From 1934 to 1944, he was the director of the Oliveriana Library of Pesaro and was involved with the Medal Collection kept in the Civic Museums of Pesaro. During his tenure, the library's headquarters in Palazzo Almerici was restored, and in 1936, the first Marche bibliographic exhibition was organized, for which Luigi Michelini Tocci curated the catalog. In 1936, he organized a preparatory course for staff of public and school libraries, conceived by the Bibliographic Superintendence of Romagna and Marche.

In November 1944, he entered the Vatican Apostolic Library and was assigned to the pontifical medal collection. In 1959, he became responsible for the numismatic cabinet of the same library, and in 1978, head of the 'Art Objects' section owned by the library. A passionate enthusiast of 19th-century literature, Renaissance Italian art, and book history, he published essays on Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, cataloged incunabula, and curated exhibition catalogs in Vatican: Quinto centenario della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1475-1975 (1975), Papal bindings from Eugene IV to Paul VI (1977), Bernini in Vatican (1981). He published monographs on Raphael Sanzio and his era, as well as on ancient artworks and architecture in Pesaro and its surroundings. He contributed to the Enciclopedia dantesca, published by Treccani.

He was entrusted with teaching the History of the Book and Libraries at the Vatican School of Librarianship and with the History of Miniature at the Vatican School of Paleography, Diplomatics, and Archival Science. He was a member of the Italian Librarians Association, for the Lazio section; a member of the Roman Society of Homeland History (since 1973); and of the Pontifical Roman Archaeological Academy, of which he was also secretary from 1971 to 1979.

Writings

Books

(FR, IT) Raffaello's father: Giovanni Santi and some of his most representative works in the Urbino and Pesaro regions, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1961, SBN MOD0376061.

Painters of the 1400s in Urbino and Pesaro, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1965, SBN MOD0299148.

The Roman medallions and the bordered pieces from the Vatican Medal Collection / described by Luigi Michelini Tocci; with an 'Appendix' concerning some silver and bronze laminae and some bronze discs. 2 volumes, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1965, SBN SBL0191781.

Pesaro Sforzesca in the inlays of the choir of S. Agostino, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1971, SBN SBL0378598.

Hermitages and cenobites of Catria, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1972, SBN SBL0436742.

Gradara and the castles on the left of the Foglia, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro, 1974, SBN SBL0571643.

ROSS. 94; The Book of Hours: a commentary volume on the facsimile edition of Cod. ROSS. 94 from the Vatican Apostolic Library, Milan, Jaca Book Codices, 1984, SBN CFI0033780.[5]

(IT, EN) In the workshop of Erasmus: the autograph apparatus of Erasmus for the 1528 edition of the Adagia and a new manuscript of the Compendium vitae, Rome, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1989, SBN LO10028371.

Written in collaboration

Image of Leon Bloy, in Studies on 19th-century literature in honor of Pietro Paolo Trompeo, Naples, Italian Scientific Editions, 1957, SBN VIA0097749.

Printed books belonging to Colocci, in Proceedings of the study conference on Angelo Colocci: Jesi, September 13-14, 1969, Città di Castello, Graphic Arts, 1972, pp. 77-96, SBN SBL0467744.

A pontifical from Cologne to Cagli in the 11th century and some essays on Cagliese writing from the 11th to 12th century, in Palaeographica, diplomatics, and archival science: studies in honor of Giulio Battelli / edited by the Special School for Archivists and Librarians of the University of Rome, vol. 1, Rome, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1979, pp. 265-294, SBN RAV0042417.

Writings for periodicals

Two Urbinati manuscripts of the privileges of Montefeltro, in La Bibliofilia, vol. 60, Florence, L. Olschki, 1959, SBN RAV0006199.

The dedication manuscript of the 'Epistola de vita et gestis Guidubaldi Urbini ducis ad Henricum Angliae regem' by Baldassarre Castiglione, in Medieval and Humanistic Italy, vol. 5, Padua, Antenore, 1962, pp. 273-282, SBN SBL0491729.

Editions

Alexis de Tocqueville, Arthur de Gobineau, Correspondence (1843-1859) / [translation from French] with introduction and notes by Luigi Michelini Tocci, Milan, Longanesi, 1947, SBN CUB0635627.

Augustin Thierry, Tales of the Merovingian Age, Milan, Longanesi, 1949, SBN LO10323661.

The Urbinate Dante of the Vatican Library: Latin Codex Urbinate 365, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1965, SBN SBL0085116.[6]

The Castles of Francesco di Giorgio, Pesaro, Cassa di Risparmio, 1967, SBN UMC0096649.

Fifth centenary of the Vatican Apostolic Library, 1475-1975: catalog of the exhibition, Vatican City, Vatican Apostolic Library, 1975, SBN SBL0173043.

Papal legatures from Eugenio IV to Paul VI: catalog of the exhibition with 211 plates, of which 35 in color, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1977, SBN BVE0590374.

(DE, IT, LA) Lamberto Donati, Luigi Michelini Tocci (editor), Biblia pauperum: reproduction of the Latin Palatino Codex 143, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1979, SBN SBL0337106.[7]

Luigi Michelini Tocci, Giovanni Morello, Valentino Martinelli, Marc Worsdale (edited by), Lorenzo Bernini, Rome, De Luca, 1981, SBN SBL0346134.

Giovanni Santi, The life and deeds of Federico di Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino: a poem in terza rima: Vat. Ottob. Lat. 1305 codex. 2 volumes, Vatican City, Vatican Library, 1985, SBN CFI0014576.[8]

The book of hours (Latin: horæ; French: livres d'heures; Spanish: horas; English: primers) is a popular Christian devotional book from the Middle Ages. It is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like any manuscript, each book of hours is unique but contains a collection of texts similar to others, such as prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often limited to decorated capital letters at the beginning of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons can be extremely sumptuous, with full-page miniatures. These illustrations would combine picturesque scenes of rural life with sacred images. Books of hours were generally written in Latin, although many are entirely or partly in European vernacular languages, particularly Dutch. Tens of thousands of books of hours have survived to this day, in libraries and private collections around the world.

Description

Image of a Book of Hours

A French book of hours from the beginning of the 15th century (MS13, Society of Antiquaries of London) opened to an illustration of the Adoration of the Magi. It was bequeathed to the Society in 1769 by the Rev. Charles Lyttleton, Bishop of Carlisle and President of the Society (1765-1768).

The typical Book of Hours is a shortened form of the breviary, containing the canonical hours recited in monasteries. It was developed for the laity eager to incorporate elements of monastic daily life into their devotional practice. The recitation of the hours typically focused on reading a certain number of psalms and other prayers.

A typical book of hours contains the Calendar of the ecclesiastical feasts (the so-called Liturgical Year), extracts from the Gospel, the readings for Mass for major feasts, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the fifteen Psalms of the Degrees, the seven Penitential Psalms, a Litany of saints, a Office for the dead, and the Hours of the Cross. Most books of hours from the 15th century have these basic contents. Marian prayers Obsecro te ('I beseech you') and O Intemerata ('O Immaculate') were frequently added, as well as devotions to be used during Mass and meditations on the Passion of Jesus among other optional texts.

Story

Example of an affordable book of hours: a 'simple' book of hours in Middle Dutch - second half of the 15th century - Duchy of Brabant.

This level of decoration is also richer than that of most books, although it is less than the sumptuous lighting found in luxury books, which are the ones most often reproduced.

The Book of Hours has its origins in the Psalter used by monks and nuns. By the 12th century, it had developed into the Breviary, with weekly cycles of psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and readings that changed with the liturgical season. Eventually, a selection of texts was produced in much shorter volumes called 'books of hours.' During the latter part of the 13th century, the book of hours became popular as a personal prayer book for men and women leading secular lives. It consisted of a selection of prayers, psalms, hymns, and lessons based on the clergy's liturgy. Each book was unique in its content, although all included the Hours of the Virgin Mary, devotions to be performed during the eight canonical hours of the day, which is the reason behind the name 'Book of Hours'.

Book of Hours by van Reynegom, c. 15th century - Royal Library of Belgium and King Baudouin Foundation.

Many books of hours were created for a female clientele. There is some evidence that they were sometimes given as wedding gifts from the husband to the bride. They were often passed down within families, as shown by wills. Until the 15th century, paper was rare, and most books of hours were made on parchment, paper, or vellum.

Although illuminated books of hours were enormously expensive, a small book with few or no miniatures was easily purchasable, to the extent that it became widely popular in the fifteenth century. The earliest surviving English example was written for a layperson living in Oxford or nearby around 1240: it is smaller than a modern pocket-sized book, well miniated in the initial letters but without full-page miniatures. In the fifteenth century, there are also examples of servants owning their own Libri d'Ore. In a legal case from 1500, a poor woman was accused of stealing a servant's book of hours.

Very rarely did books include prayers composed specifically for their owners, but more often the texts were adapted to their tastes or gender, including the owners' names in the prayers. Some include images depicting the owners and/or their coats of arms. These, along with the choice of saints commemorated in the calendar and the prayers, are the main clues to the identity of the patron. Eamon Duffy explains that 'the personal character of these books has often been indicated by the inclusion of prayers specially composed or adapted for their owners.' Furthermore, he states that 'up to half of the surviving handwritten books of hours contain annotations, marginalia, or additions of some kind. Such additions might not amount to the inclusion of a regional or personal patron saint in the standardized calendar but often include devotional material added by the owner. Owners could write in specific dates important to them, notes about the months in which events they wished to remember occurred, and even the images found within these books would be personalized for the owners, such as localized saints and local festivals.'

At least in the 15th century, Dutch and Parisian workshops produced books of hours for distribution, without waiting for individual commissions. These were sometimes made with spaces left for the addition of personalized elements such as local festivals or heraldry.

Black bulls, Morgan MS 493, Pentecost, folios 18v/19r, circa 1475–80. Morgan Library & Museum, New York

The style and arrangement of traditional Books of Hours became increasingly standardized around the mid-13th century. The new style can be seen in the books produced by the Oxford illuminator William de Brailes, a member of the minor orders who managed a commercial workshop. His books included various aspects of the Breviary and other liturgical elements for lay use. "He incorporated a perpetual calendar, Gospels, prayers to the Virgin Mary, the Way of the Cross, prayers to the Holy Spirit, penitential Psalms, litanies, prayers for the dead, and suffrages to the Saints. The book's goal was to help his devout patroness structure her daily spiritual life according to the eight canonical hours, from Matins to Compline, observed by all devout members of the Church. The text, enriched with rubrics, gilding, miniatures, and beautiful illuminations, aimed to inspire meditation on the mysteries of faith, the sacrifice made by Christ for mankind, and the horrors of hell, while particularly emphasizing devotion to the Virgin Mary, whose popularity peaked during the 13th century." This arrangement persisted over the years as many aristocrats commissioned their own Books of Hours.

By the end of the 15th century, the advent of printing made books more affordable, and much of the emerging middle class could afford to purchase a printed book of hours, with new manuscripts being commissioned only by the wealthiest. The first printed book of hours in Italy dates to 1472 in Venice, by J. Nelson, while production also began in Naples from 1476 (Moravo-Preller). In 1478, W. Caxton produced the first printed book of hours in England at Westminster, while the Netherlands (Brussels and Delft) began printing books of hours in 1480. These were books decorated with woodcuts, initially in limited numbers and increasingly more common.[9] In France, printers instead employed engravers to emulate the miniatures scattered throughout the page typical of handwritten books of hours, then printing on parchment rather than paper and not hesitating to have the drawings hand-colored: e.g., the printed book of hours in 1487 by Antoine Vérard.[10]

The Kitāb ṣalāt al‐sawā'ī (1514), widely considered the first book in Arabic printed with movable type, is a book of hours intended for Arabic-speaking Christians and presumably commissioned by Pope Julius II.

Decoration

A full-page miniature from May, from a calendar cycle by Simon Bening, early 16th century.

Since many Books of Hours are richly illuminated, they serve as important evidence of life in the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as iconography of medieval Christianity. Some of them were also decorated with jeweled covers, portraits, and heraldic emblems. A few were bound as belt books for easy transport, although few of these or other medieval bindings have survived. Luxury books, such as the Talbot Hours of John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, may include a portrait of the owner, and in this case, his wife, kneeling in adoration of the Virgin with Child as a form of donor portrait. In expensive books, miniature cycles depicted the Life of the Virgin or the Passion of Christ in eight scenes that decorate the eight Hours of the Virgin, as well as the Labors of the Months and the zodiac signs that adorn the calendar. Secular scenes in the calendar cycles include many of the most well-known images from Books of Hours and played an important role in the early history of landscape painting.

From the 14th century, decorated borders around the edges of at least important pages were common in heavily illuminated books, including books of hours. At the beginning of the 15th century, these were still usually based on foliage drawings and paintings on a simple background, but in the second half of the century, colored or fantasy backgrounds with images of all kinds of objects were used in luxury books.

Second-hand books of hours were often modified by their new owners, even among royalty. After defeating his rival Riccardo III, Henry VII of England gave his book of hours to his mother, who altered it to include her own name. Heraldry was usually erased or over-painted by new owners. Many contained handwritten annotations, personal additions, and marginal notes, but some new owners also commissioned artisans to add more illustrations or texts. Sir Thomas Lewkenor of Trotton hired an illustrator to add details to what is now known as the Lewkenor Hours. The pastedowns of some surviving books include notes of household accounts or birth and death records, similar to later family Bibles. Some owners also collected autographs of important visitors to their homes. Books of hours were often the only book in a household and were commonly used to teach children to read, sometimes featuring a page with the alphabet to assist them.

Towards the end of the 15th century, printers produced books of hours with woodcut illustrations, and the book of hours was one of the main decorated works using the related metal engraving technique.

The luxury book of hours

The illusionistic boundaries of this Flemish book of hours from the late 15th century are typical of luxury books from this period, which were often decorated on every page. The butterfly wing that cuts across the text area is an example of a play with visual conventions, typical of the era.

Among the plants are Veronica, Vinca, Viola tricolor, Bellis perennis, and Chelidonium majus. The butterfly at the bottom is Aglais urticae, and the butterfly at the top left is Pieris rapae. The Latin text is a devotion to Saint Christopher.

In the 14th century, the book of hours surpassed the psalter as the most common vehicle for luxury miniatures, demonstrating the now established dominance of lay patronage over religious patronage for miniatures. From the late 14th century, a number of crowned bibliophiles began collecting luxurious illuminated manuscripts for their decorations, a fashion that spread throughout Europe from the courts of the Valois in France and Burgundy, as well as in Prague under Charles IV of Luxembourg and later Wenceslaus of Luxembourg. A generation later, Duke Philip III of Burgundy was the most important collector of illuminated manuscripts, and many of his circle were as well. It was during this period that Flemish cities emerged as a driving force in miniature, a position they maintained until the decline of illuminated manuscripts in the early 16th century.

The most famous collector of all, the French prince Giovanni di Valois, Duke of Berry (1340–1416), owned several books of hours, some of which survive, including the most renowned of all, the Très riches heures du Duc de Berry. This work was begun around 1410 by the Limbourg brothers, although left incomplete, and its decoration continued for several decades by other artists and patrons. The same was true for the Hours of Turin, which were also owned, among others, by the Duke of Berry.

By the mid-15th century, a much broader group of nobility and wealthy businessmen was able to commission highly decorated books of hours, often small in size. With the advent of printing, the market sharply contracted, and by 1500, the finest quality books were produced again only for royal or very grand collectors. One of the last great illuminated books of hours was the so-called Farnese Hours of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese the Younger, created in 1546 by Giulio Clovio, the last great manuscript miniaturist.