William Cowper - ELEPHANT FOLIO The anatomy of humane bodies with figures drawn after the life by some of the best - 1698

Add to your favourites to get an alert when the auction starts.

Specialist in travel literature and pre-1600 rare prints with 28 years experience.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 121798 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

Description from the seller

William Cowper, The anatomy of humane bodies with figures drawn after the life by some of the best masters in Europe and curiously engraven in one hundred and fourteen copper plates: illustrated with large explications containing many new anatomical discoveries and chirurgical observations: to which is added an introduction explaining the animal œconomy: with a copious index. Oxford, printed at the Theater, for S. Smith and B. Walford, 1698.

Large folio (64 x 43cm), with mezzotint frontispiece portrait of the author, allegorical engraved title with pasted-on English title in cartouche as usual, a second engraved title with a large vignette, [138] pages and 114 engraved anatomical plates (two folding, of which one printed on two joined sheets), for the greater part after drawings by G. de Lairesse.

Complete first edition. All pages are mounted on large tabs. An extra large-margined copy: rare.

Bound in contemporary blind-tooled calf (skillfully rebacked in antique style with modern red calf label). All leaves and plates are mounted on stubs; the mezzotint portrait is laid down. The lower sheet of plate 10 is a little damaged and laid down; a closed tear appears on the dedication leaves; the fore-edge of some plates cut short, and there is some slight and occasional toning.

Garrison-Morton 385.1 write that this is

''''The most elaborate and beautiful of all 17th century English treatises on anatomy and also one of the most extraordinary plagiarisms in the entire history of medicine. Cowper purchased sets of the van Gunst copperplates used to illustrate Bidloo's book and issued them under his own name with an English text and a new illustrated appendix. For the frontispiece Cowper had a small printed flap with his own name pasted over Bidloo's own engraved title and name.'''

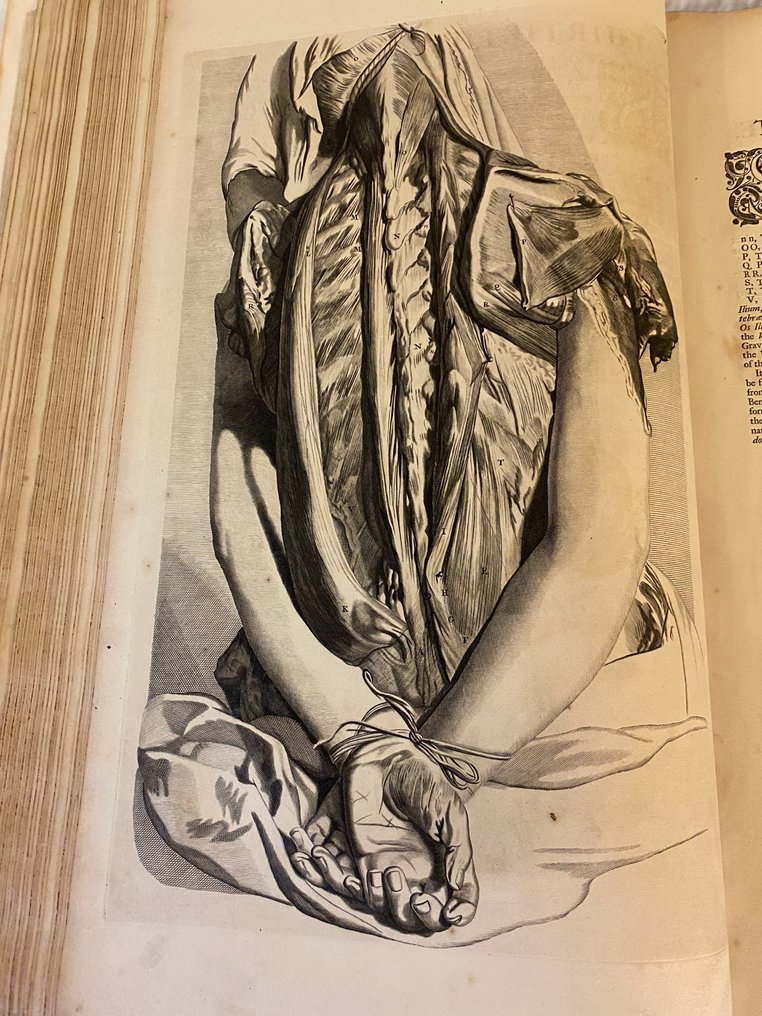

The nine new plates that Cowper commissioned, drawn by Cooke and engraved by van der Gucht, include front and back views of the entire musculature (see Heirs of Hippocrates 723.9)

THE BOOK

It is both a seminal piece of medical literature and, by way of the controversy it generated, a fascinating illustration of an early international intellectual property dispute. Containing dozens of accomplished, intricate and sometimes even disturbing plates, Cowper's work and the debate it generated serve as both an anatomy of the body and an anatomy of copyright law as it existed (or did not exist) at the end of the 17th Century.

Cowper’s Anatomy was instrumental in changing the standard approach to the study of anatomy and the practice of surgery. The book is extraordinarily large in size, and weighing approximately 9 kilograms. At the time of publication, the book was one of the most authoritative and comprehensive atlases of human anatomy. [Fenwick Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists,’ Annals of Medical History 7 (1935): 117.]

It was superior in quality of both the illustrations and the text to other atlases of anatomy and was produced for the benefit and advancement of the study of anatomy, including new research and discovery [Mark A. Sanders, ‘William Cowper and His Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anat.) 282B, (2005): 6].

The captions, accompanying the illustrations, reflect the spelling and the letter fonts in usage at the time of publication in 1698.

William Cowper was a renowned surgeon and anatomist, practicing in London. He became one of the first two surgeons ever elected membership in the Royal Society in 1696 and produced several publications about his anatomical research and discoveries. He established his authority with the publication of his 1694 Myotomia Reformata describing the human body’s muscular system. For his 1698 Anatomy, Cowper wrote text to accompany the 114 images. He based his writing on his own observations and experiences as an anatomist and a surgeon. He included his suggestions and discoveries in his commentary.

The extent to which Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies influenced the late 17th century study of anatomy and surgery is debatable. Some critics find fault with the text because the illustrations are not anatomically accurate [Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists,’ 119-120]. However, others argue that Cowper’s text provided a thorough accompaniment to, and explanation of, the (otherwise flawed) anatomic illustrations [Sanders, ‘Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ 6].

In this discussion, it is relevant to consider that following the 1698 publication, the study of anatomy increased and several new schools of anatomy were established. Following Cowper’s lead, British surgeons began to take the study of their vocation more seriously and were less ‘content with the vague humoral pathology of the ancient surgeons.’ [Robert F. Buckman Jr. and J. William Futrell, ‘William Cowper,’ Surgery 99/5 (1986): 589].

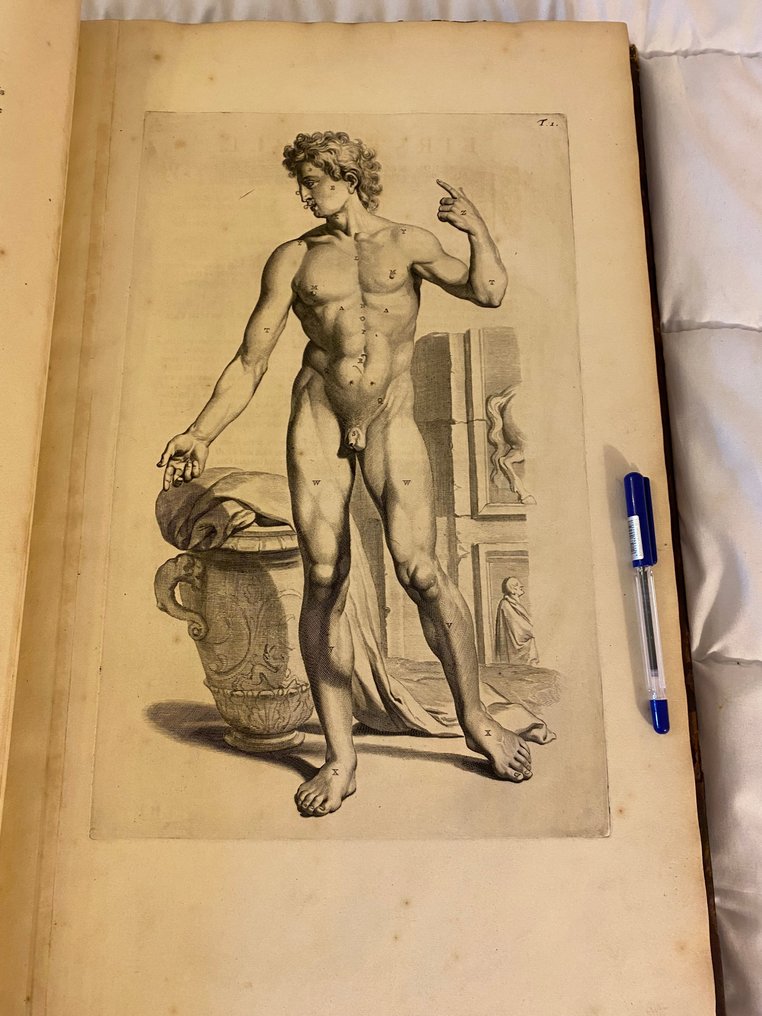

While Cowper’s text is impressive for its detail, emphasis on instruction, and evidence of discovery, the Anatomy is also remarkable for its intricate, delicate illustrations that capture the various scenes of dissection in minute detail. The artist for the majority of the plates was the Dutch painter Gérard de Lairesse. De Lairesse was well-known for his classical French style and was even referred to as the ‘Dutch Poussin' [Horton A. Johnson, ‘Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes,’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97/ 6 (2004): 302.] He was proficient and popular through the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His anatomical illustrations marked a shift to realistic portrayals of anatomy subjects, contributing to the progress of the study of anatomy. De Lairesse portrays his subjects in classical poses and spares no detail in his representation of the subject. For Cowper to include detailed and specific text, the images from which he worked had to be the same. The reader can see represented all the tools used in the dissection, including the pins, ropes, and props used to position the body parts. De Lairesse captures the detail of his subjects’ skin, face, hair, and hands, without sacrificing any anatomic detail. The result is numerous plates that pair artistic beauty with graphic detail and the images can be quite disturbing and moving. The artist also expresses a poetic sense of humour, sketching a stray fly or a smiling skeleton holding an hour glass in a mausoleum. One critic calls de Lairesse’s work ‘a masterpiece of Dutch baroque art.’ [Paolo Santoni-Rugiu and Philip J. Sykes, A History of Plastic Surgery (New York: 2007): 32].

PLAGIARISM

While Cowper’s Anatomy is remarkable on its own, it is important to consider the controversy surrounding its publication. Prior to Cowper’s publication, Govard Bidloo published his Anatomia humani corporis in 1685. Bidloo was a famous Dutch physician and anatomist. He was the physician to King William of Orange and was a professor of anatomy at the Hague and the University of Leiden. Bidloo was the original author to publish the 105 copperplates designed by de Lairesse that were used in Cowper’s 1698 text. Bidloo originally accompanied the plates with a brief Latin text and published a second, Dutch edition in 1690. Unlike Cowper’s Anatomy, neither of Bidloo’s editions sold many copies, perhaps due to his limited text. It is from this second edition that Cowper is believed to have acquired the plates.

Just how Cowper acquired the plates remains a matter of contention. Some reports indicate Cowper’s publishers purchased the plates from Bidloo’s publishers and simply asked Cowper to write English text [Sanders, ‘Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ 7]. However, more popular accounts argue that Cowper was actively involved in the acquisition of the plates, with some contending he travelled to Leiden on multiple occasions to secure the plates under false pretences [Santoni-Rugiu and Sykes, History, 32].

Regardless of the method of acquisition, Cowper acquired Bidloo’s plates and published them in his 1698 Anatomy with his new, more extensive accompanying text. Reusing plates was not uncommon in the 17th century. In fact, Cowper reused plates from his 1694 Myotomia in his appendix to the Anatomy. It is Cowper’s original, extensive text that adds value to the work and fuel to the controversy. The tone of his text is critical of Bidloo’s work. Cowper has added letters in red ink to Bidloo’s prints to indicate additional observations or references. This is clearly visible in our first edition. Cowper also added 9 additional plates in an appendix where he believed Bidloo’s work failed to properly express or cover relevant information. Other differences between the two texts include Cowper’s use of various decorative cartouches that are thematically relevant to the subject to fill blank space and his implementation of decorative initials to begin most pages of text. Cowper also replaced the portrait of Bidloo with one of his own and pasted his name and title over Bidloo’s in the frontispiece.

Many critics have claimed that Cowper committed one of the most egregious acts of plagiarism in medical history [Choulant, Ludwig, History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration, trans. Mortimer Frank (1962): 250-253 for the Cowper/Bidloo case. Gysel, C. 'L'Anatomia de Govert Bidloo (1685) et le plagiat de William Cowper (1698)', Revue Belge de médecine dentaire 42 (1987): 96-101. Norman, Jeremy (ed.). Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography: A Check-list of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine 1470-1960 (1991): 385.1; commentary discusses the controversy. William Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies (U Windsor Leddy Library digital exhibit) — provides context and detailed discussion of acquisition and reuse of plates].

Bidloo himself wrote a denunciation [Bidloo, Govard. Gulielmus Cowper, criminis literarii citatus coram tribunali nobiliss. ampliss. Societatis Britanno¬ræ regiæ (Leiden: [publisher], 1700). A printed accusation by Bidloo against Cowper. Cowper, William. Eucharistia : in qua dotes plurimæ & singulares Godefridi Bidloo, M.D. … celebrantur et ejusdem citationi humillime respondetur. (London: [publisher], 1701) is Cowper’s rejoinder to Bidloo.].

It is important to consider that our contemporary understanding of plagiarism does not apply to the latter part of the 17th century, when copyright law was still in a state of flux. The Statute of Anne, Britain’s first real copyright law, was not invoked until 1710 and there existed no international copyright law between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Also, the plates were legally purchased from Bidloo’s publishers. As Bidloo’s legal rights were not violated, it is interesting to consider why this case created so much discussion and controversy.

While not a legal offence, it is arguable that Cowper perpetrated a moral transgression by using Bidloo’s plates. Bidloo was deeply outraged and claimed that Cowper published his plates without properly crediting him [’Archæologica Medica: XLI. William Cowper, the Anatomist,’ British Medical Journal 1/1933 (Jan 15 1898): 160].

Cowper does credit de Lairesse as the artist of the plates and states they were previously published by Bidloo in his ‘To the Reader section.’ Many argue, as did Bidloo, that burying this recognition in the middle of text, rather than prominently crediting Bidloo, signifies Cowpers’ transgression against Bidloo’s intellectual property [Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper,’ 127].

As Bidloo had no legal recourse, he petitioned the Royal Society to revoke Cowper’s member status and wrote a series of pamphlets admonishing Cowper’s actions. Cowper denied Bidloo’s accusations, stating that he had credited Bidloo in his book and that he had written a completely new text to accompany the plates. Cowper also suggested the plates had actually been commissioned for an anatomist by the name of Swammerdam and Bidloo had obtained them after the former’s death. This claim, however, was never substantiated. Further evidence of Cowper’s appropriation of Bidloo’s work is his act of pasting his name and title over Bidloo’s in the frontispiece of the book. As our edition suffered minor damage and was subsequently repaired, researchers can see where Cowper’s title is no longer in place and the original print of Bidloo’s Dutch edition remains. While Cowper may not have committed a crime, it is clear that he had an influence on the discussion of copyright law and academic integrity in the late 17th century and beyond.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Archæologica Medica: XLI. William Cowper, the Anatomist.’ British Medical Journal 1/ 1933 (Jan 15 1898):160-178.

Beekman, Fenwick. ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists.’ Annals of Medical History 7 (1935): 113-129.

Bibliotheca Walleriana: The books illustrating the history of medicine and science collected by Dr Erik Waller (1955): Waller 2192.

Bidloo, Govard. Gulielmus Cowper, criminis literarii citatus coram tribunali nobiliss. ampliss. Societatis Britanno¬ræ regiæ (Leiden: [publisher], 1700).

Buckman, Robert F. Jr., and J. William Futrell. ‘William Cowper.’ Surgery 99/ 5 (1986): 582-590.

Choulant, Ludwig, History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration, trans. Mortimer Frank (1962): 250-253.

Cole, Francis J., The Cole Library catalogue of early works on anatomy and zoology (1986): 1113.

Cowper, William. The Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Oxford: Samuel Smith and Benjamin Walford, 1698.

----. Eucharistia : in qua dotes plurimæ & singulares Godefridi Bidloo, M.D. … celebrantur et ejusdem citationi humillime respondetur. (London: [publisher], 1701.

Dumaitre, Pierre, La curieuse destinée des planches anatomiques de Gérard de Lairesse (1982).

Gysel, C. 'L'Anatomia de Govert Bidloo (1685) et le plagiat de William Cowper (1698)', Revue Belge de médecine dentaire 42 (1987): 96-101.

Johnson, Horton A. ‘Gerard de Lairesse: Genius Among the Treponemes.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97/ 6 (2004): 301-03.

Kornell, Monique. ‘Cowper, William (1666/7-1710).’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford [accessed 16 October 2025]

McIntosh, W.A. ‘Cowper – The Anatomist.’ The Canadian Medical Association Journal 10/10 (1920): 938 – 945.

Norman, Jeremy (ed.). Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography: A Check-list of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine 1470-1960 (1991): 385.1.

K.B. Roberts, K.B. and J.D.W. Tomlinson, The Fabric of the Body: European traditions of anatomical illustration (1992).

Russell, K. F., British anatomy 1525-1800: a bibliography of works published in Britain, America and on the Continent (1987): entries 211-214 cover Cowper’s work.

Santoni-Rugiu, Paolo, and Philip J. Sykes. A History of Plastic Surgery (2007).

Sanders, Mark A. ‘William Cowper and His Decorated Copperplate Initials.’ The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anat.) 282B (2005): 5-12.

Thomas, Bryn K. ‘The Great Anatomical Atlases.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 67/ 3 (1974): 223-232.

William Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies (U Windsor Leddy Library digital exhibit). https://leddy.uwindsor.ca/exhibits-digital-collections/william-cowpers-anatomy-humane-bodies.

CURRENTLY OFFERED FOR SALE/SOLD

No copies of the first edition as listed here are currently offered for sale.

Jeremy Norman offered a first edition (as here), also rebacked for $15,000 (2011, Catalogue 41)

William Cowper, The anatomy of humane bodies with figures drawn after the life by some of the best masters in Europe and curiously engraven in one hundred and fourteen copper plates: illustrated with large explications containing many new anatomical discoveries and chirurgical observations: to which is added an introduction explaining the animal œconomy: with a copious index. Oxford, printed at the Theater, for S. Smith and B. Walford, 1698.

Large folio (64 x 43cm), with mezzotint frontispiece portrait of the author, allegorical engraved title with pasted-on English title in cartouche as usual, a second engraved title with a large vignette, [138] pages and 114 engraved anatomical plates (two folding, of which one printed on two joined sheets), for the greater part after drawings by G. de Lairesse.

Complete first edition. All pages are mounted on large tabs. An extra large-margined copy: rare.

Bound in contemporary blind-tooled calf (skillfully rebacked in antique style with modern red calf label). All leaves and plates are mounted on stubs; the mezzotint portrait is laid down. The lower sheet of plate 10 is a little damaged and laid down; a closed tear appears on the dedication leaves; the fore-edge of some plates cut short, and there is some slight and occasional toning.

Garrison-Morton 385.1 write that this is

''''The most elaborate and beautiful of all 17th century English treatises on anatomy and also one of the most extraordinary plagiarisms in the entire history of medicine. Cowper purchased sets of the van Gunst copperplates used to illustrate Bidloo's book and issued them under his own name with an English text and a new illustrated appendix. For the frontispiece Cowper had a small printed flap with his own name pasted over Bidloo's own engraved title and name.'''

The nine new plates that Cowper commissioned, drawn by Cooke and engraved by van der Gucht, include front and back views of the entire musculature (see Heirs of Hippocrates 723.9)

THE BOOK

It is both a seminal piece of medical literature and, by way of the controversy it generated, a fascinating illustration of an early international intellectual property dispute. Containing dozens of accomplished, intricate and sometimes even disturbing plates, Cowper's work and the debate it generated serve as both an anatomy of the body and an anatomy of copyright law as it existed (or did not exist) at the end of the 17th Century.

Cowper’s Anatomy was instrumental in changing the standard approach to the study of anatomy and the practice of surgery. The book is extraordinarily large in size, and weighing approximately 9 kilograms. At the time of publication, the book was one of the most authoritative and comprehensive atlases of human anatomy. [Fenwick Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists,’ Annals of Medical History 7 (1935): 117.]

It was superior in quality of both the illustrations and the text to other atlases of anatomy and was produced for the benefit and advancement of the study of anatomy, including new research and discovery [Mark A. Sanders, ‘William Cowper and His Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anat.) 282B, (2005): 6].

The captions, accompanying the illustrations, reflect the spelling and the letter fonts in usage at the time of publication in 1698.

William Cowper was a renowned surgeon and anatomist, practicing in London. He became one of the first two surgeons ever elected membership in the Royal Society in 1696 and produced several publications about his anatomical research and discoveries. He established his authority with the publication of his 1694 Myotomia Reformata describing the human body’s muscular system. For his 1698 Anatomy, Cowper wrote text to accompany the 114 images. He based his writing on his own observations and experiences as an anatomist and a surgeon. He included his suggestions and discoveries in his commentary.

The extent to which Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies influenced the late 17th century study of anatomy and surgery is debatable. Some critics find fault with the text because the illustrations are not anatomically accurate [Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists,’ 119-120]. However, others argue that Cowper’s text provided a thorough accompaniment to, and explanation of, the (otherwise flawed) anatomic illustrations [Sanders, ‘Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ 6].

In this discussion, it is relevant to consider that following the 1698 publication, the study of anatomy increased and several new schools of anatomy were established. Following Cowper’s lead, British surgeons began to take the study of their vocation more seriously and were less ‘content with the vague humoral pathology of the ancient surgeons.’ [Robert F. Buckman Jr. and J. William Futrell, ‘William Cowper,’ Surgery 99/5 (1986): 589].

While Cowper’s text is impressive for its detail, emphasis on instruction, and evidence of discovery, the Anatomy is also remarkable for its intricate, delicate illustrations that capture the various scenes of dissection in minute detail. The artist for the majority of the plates was the Dutch painter Gérard de Lairesse. De Lairesse was well-known for his classical French style and was even referred to as the ‘Dutch Poussin' [Horton A. Johnson, ‘Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes,’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97/ 6 (2004): 302.] He was proficient and popular through the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His anatomical illustrations marked a shift to realistic portrayals of anatomy subjects, contributing to the progress of the study of anatomy. De Lairesse portrays his subjects in classical poses and spares no detail in his representation of the subject. For Cowper to include detailed and specific text, the images from which he worked had to be the same. The reader can see represented all the tools used in the dissection, including the pins, ropes, and props used to position the body parts. De Lairesse captures the detail of his subjects’ skin, face, hair, and hands, without sacrificing any anatomic detail. The result is numerous plates that pair artistic beauty with graphic detail and the images can be quite disturbing and moving. The artist also expresses a poetic sense of humour, sketching a stray fly or a smiling skeleton holding an hour glass in a mausoleum. One critic calls de Lairesse’s work ‘a masterpiece of Dutch baroque art.’ [Paolo Santoni-Rugiu and Philip J. Sykes, A History of Plastic Surgery (New York: 2007): 32].

PLAGIARISM

While Cowper’s Anatomy is remarkable on its own, it is important to consider the controversy surrounding its publication. Prior to Cowper’s publication, Govard Bidloo published his Anatomia humani corporis in 1685. Bidloo was a famous Dutch physician and anatomist. He was the physician to King William of Orange and was a professor of anatomy at the Hague and the University of Leiden. Bidloo was the original author to publish the 105 copperplates designed by de Lairesse that were used in Cowper’s 1698 text. Bidloo originally accompanied the plates with a brief Latin text and published a second, Dutch edition in 1690. Unlike Cowper’s Anatomy, neither of Bidloo’s editions sold many copies, perhaps due to his limited text. It is from this second edition that Cowper is believed to have acquired the plates.

Just how Cowper acquired the plates remains a matter of contention. Some reports indicate Cowper’s publishers purchased the plates from Bidloo’s publishers and simply asked Cowper to write English text [Sanders, ‘Decorated Copperplate Initials,’ 7]. However, more popular accounts argue that Cowper was actively involved in the acquisition of the plates, with some contending he travelled to Leiden on multiple occasions to secure the plates under false pretences [Santoni-Rugiu and Sykes, History, 32].

Regardless of the method of acquisition, Cowper acquired Bidloo’s plates and published them in his 1698 Anatomy with his new, more extensive accompanying text. Reusing plates was not uncommon in the 17th century. In fact, Cowper reused plates from his 1694 Myotomia in his appendix to the Anatomy. It is Cowper’s original, extensive text that adds value to the work and fuel to the controversy. The tone of his text is critical of Bidloo’s work. Cowper has added letters in red ink to Bidloo’s prints to indicate additional observations or references. This is clearly visible in our first edition. Cowper also added 9 additional plates in an appendix where he believed Bidloo’s work failed to properly express or cover relevant information. Other differences between the two texts include Cowper’s use of various decorative cartouches that are thematically relevant to the subject to fill blank space and his implementation of decorative initials to begin most pages of text. Cowper also replaced the portrait of Bidloo with one of his own and pasted his name and title over Bidloo’s in the frontispiece.

Many critics have claimed that Cowper committed one of the most egregious acts of plagiarism in medical history [Choulant, Ludwig, History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration, trans. Mortimer Frank (1962): 250-253 for the Cowper/Bidloo case. Gysel, C. 'L'Anatomia de Govert Bidloo (1685) et le plagiat de William Cowper (1698)', Revue Belge de médecine dentaire 42 (1987): 96-101. Norman, Jeremy (ed.). Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography: A Check-list of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine 1470-1960 (1991): 385.1; commentary discusses the controversy. William Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies (U Windsor Leddy Library digital exhibit) — provides context and detailed discussion of acquisition and reuse of plates].

Bidloo himself wrote a denunciation [Bidloo, Govard. Gulielmus Cowper, criminis literarii citatus coram tribunali nobiliss. ampliss. Societatis Britanno¬ræ regiæ (Leiden: [publisher], 1700). A printed accusation by Bidloo against Cowper. Cowper, William. Eucharistia : in qua dotes plurimæ & singulares Godefridi Bidloo, M.D. … celebrantur et ejusdem citationi humillime respondetur. (London: [publisher], 1701) is Cowper’s rejoinder to Bidloo.].

It is important to consider that our contemporary understanding of plagiarism does not apply to the latter part of the 17th century, when copyright law was still in a state of flux. The Statute of Anne, Britain’s first real copyright law, was not invoked until 1710 and there existed no international copyright law between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Also, the plates were legally purchased from Bidloo’s publishers. As Bidloo’s legal rights were not violated, it is interesting to consider why this case created so much discussion and controversy.

While not a legal offence, it is arguable that Cowper perpetrated a moral transgression by using Bidloo’s plates. Bidloo was deeply outraged and claimed that Cowper published his plates without properly crediting him [’Archæologica Medica: XLI. William Cowper, the Anatomist,’ British Medical Journal 1/1933 (Jan 15 1898): 160].

Cowper does credit de Lairesse as the artist of the plates and states they were previously published by Bidloo in his ‘To the Reader section.’ Many argue, as did Bidloo, that burying this recognition in the middle of text, rather than prominently crediting Bidloo, signifies Cowpers’ transgression against Bidloo’s intellectual property [Beekman, ‘Bidloo and Cowper,’ 127].

As Bidloo had no legal recourse, he petitioned the Royal Society to revoke Cowper’s member status and wrote a series of pamphlets admonishing Cowper’s actions. Cowper denied Bidloo’s accusations, stating that he had credited Bidloo in his book and that he had written a completely new text to accompany the plates. Cowper also suggested the plates had actually been commissioned for an anatomist by the name of Swammerdam and Bidloo had obtained them after the former’s death. This claim, however, was never substantiated. Further evidence of Cowper’s appropriation of Bidloo’s work is his act of pasting his name and title over Bidloo’s in the frontispiece of the book. As our edition suffered minor damage and was subsequently repaired, researchers can see where Cowper’s title is no longer in place and the original print of Bidloo’s Dutch edition remains. While Cowper may not have committed a crime, it is clear that he had an influence on the discussion of copyright law and academic integrity in the late 17th century and beyond.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Archæologica Medica: XLI. William Cowper, the Anatomist.’ British Medical Journal 1/ 1933 (Jan 15 1898):160-178.

Beekman, Fenwick. ‘Bidloo and Cowper, Anatomists.’ Annals of Medical History 7 (1935): 113-129.

Bibliotheca Walleriana: The books illustrating the history of medicine and science collected by Dr Erik Waller (1955): Waller 2192.

Bidloo, Govard. Gulielmus Cowper, criminis literarii citatus coram tribunali nobiliss. ampliss. Societatis Britanno¬ræ regiæ (Leiden: [publisher], 1700).

Buckman, Robert F. Jr., and J. William Futrell. ‘William Cowper.’ Surgery 99/ 5 (1986): 582-590.

Choulant, Ludwig, History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration, trans. Mortimer Frank (1962): 250-253.

Cole, Francis J., The Cole Library catalogue of early works on anatomy and zoology (1986): 1113.

Cowper, William. The Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Oxford: Samuel Smith and Benjamin Walford, 1698.

----. Eucharistia : in qua dotes plurimæ & singulares Godefridi Bidloo, M.D. … celebrantur et ejusdem citationi humillime respondetur. (London: [publisher], 1701.

Dumaitre, Pierre, La curieuse destinée des planches anatomiques de Gérard de Lairesse (1982).

Gysel, C. 'L'Anatomia de Govert Bidloo (1685) et le plagiat de William Cowper (1698)', Revue Belge de médecine dentaire 42 (1987): 96-101.

Johnson, Horton A. ‘Gerard de Lairesse: Genius Among the Treponemes.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97/ 6 (2004): 301-03.

Kornell, Monique. ‘Cowper, William (1666/7-1710).’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford [accessed 16 October 2025]

McIntosh, W.A. ‘Cowper – The Anatomist.’ The Canadian Medical Association Journal 10/10 (1920): 938 – 945.

Norman, Jeremy (ed.). Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography: A Check-list of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine 1470-1960 (1991): 385.1.

K.B. Roberts, K.B. and J.D.W. Tomlinson, The Fabric of the Body: European traditions of anatomical illustration (1992).

Russell, K. F., British anatomy 1525-1800: a bibliography of works published in Britain, America and on the Continent (1987): entries 211-214 cover Cowper’s work.

Santoni-Rugiu, Paolo, and Philip J. Sykes. A History of Plastic Surgery (2007).

Sanders, Mark A. ‘William Cowper and His Decorated Copperplate Initials.’ The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anat.) 282B (2005): 5-12.

Thomas, Bryn K. ‘The Great Anatomical Atlases.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 67/ 3 (1974): 223-232.

William Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies (U Windsor Leddy Library digital exhibit). https://leddy.uwindsor.ca/exhibits-digital-collections/william-cowpers-anatomy-humane-bodies.

CURRENTLY OFFERED FOR SALE/SOLD

No copies of the first edition as listed here are currently offered for sale.

Jeremy Norman offered a first edition (as here), also rebacked for $15,000 (2011, Catalogue 41)