François Guizot - Histoire de la Révolution d'Angleterre - 1858-1859

Specialist in travel literature and pre-1600 rare prints with 28 years experience.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 122385 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

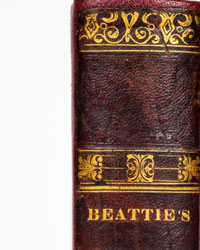

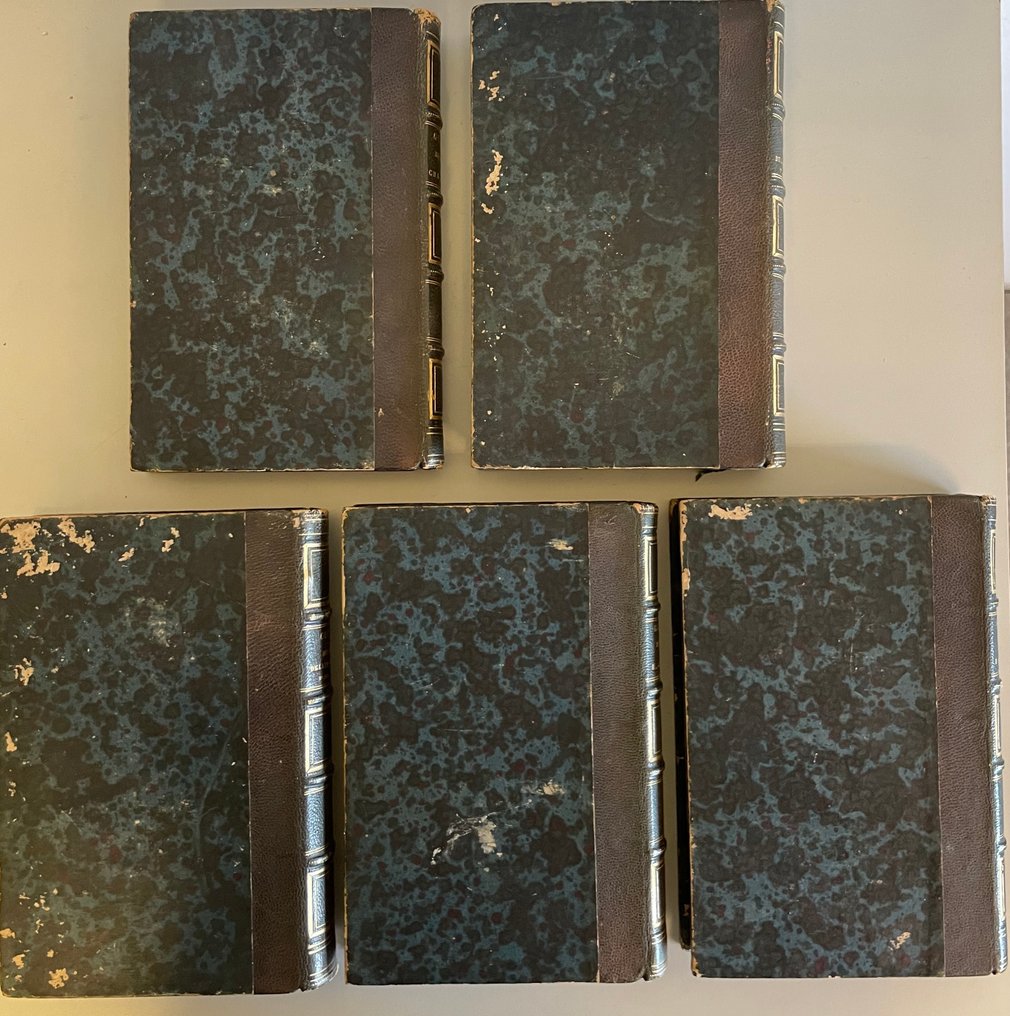

Five-volume set of Histoire de la Révolution d'Angleterre by François Guizot, published 1858–1859 by Paris Didier et Cie, Libraires-Editeur, in good condition with hardcover bindings and gilt-tooled spines.

Description from the seller

5 volumes of M. Guizot's work in 6 volumes 'Histoire de la Révolution d'Angleterre.'

The first volume of the first part of the work is missing: Histoire de Charles Ier depuis son avènement jusqu'à sa mort (1625-1649).

History of the English Revolution

Consisting of 3 parts

- History of Charles I from his accession to his death (1625-1649) (sixth edition, 1858) - Only the second volume is presented; the first volume is missing.

History of the Republic of England and Cromwell (1649-1658) (new edition, 1859) - Present the two volumes

History of the Protectorate of Richard Cromwell and the Restoration of the Stuarts 1658-1660 (new edition, 1859) - Present the two volumes

Author: François Pierre Guillaume Guizot [1787-1874]

Years: 1858-59

Publishing House: Paris - Didier et Cie, Booksellers-Publisher

Dimensions: 18.5 x 11.8 cm

Pages: 2552 total: 413 (second volume) - (VII) 524 (first volume) - 654 (second volume) - (VIII) 507 (first volume) - 439 (second volume) -

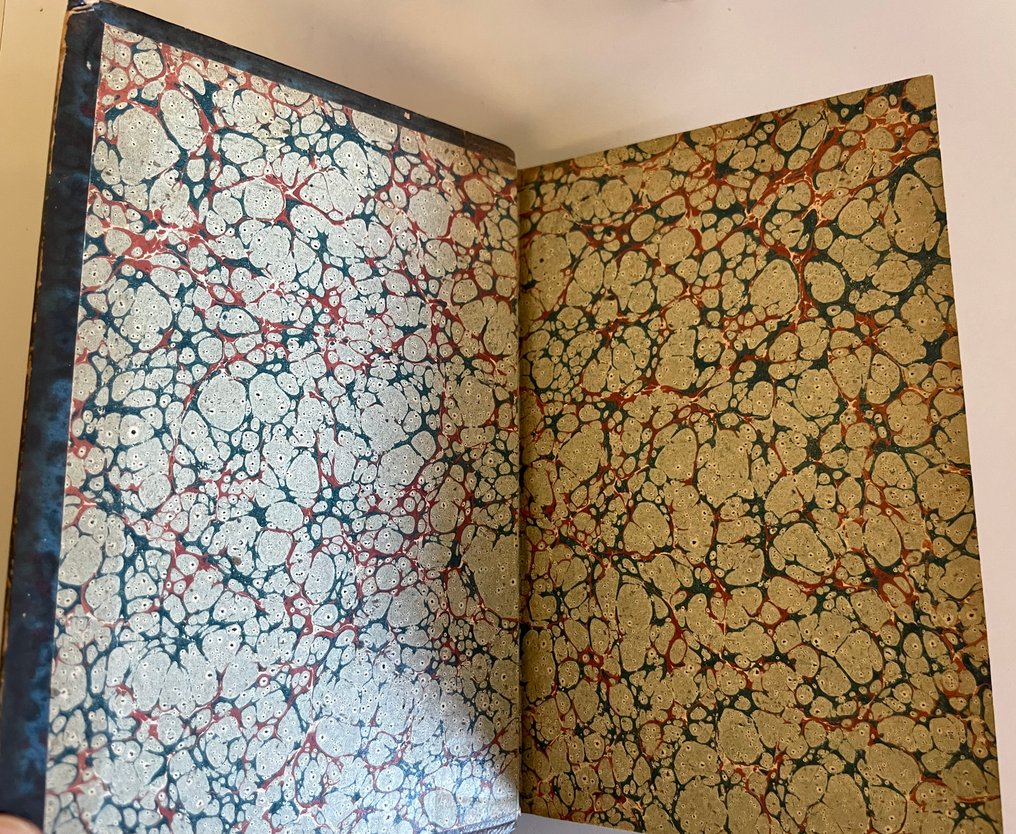

Non-editorial hardcover covers with spine ribs and titles on the back.

In good condition: good pages with browning, excellent covers (see the photos).

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot /fʁɑ̃ˈswa giˈzo/ (Nîmes, October 4, 1787 – Abbey of Val-Richer, September 12, 1874) was a French politician and historian.

Born in Nîmes to a Huguenot bourgeois family. His parents secretly married in a Catholic ceremony. On April 8, 1794, his father, Andrea Guizot, accused of federalism, was executed in Nîmes during the height of the Terror. From that moment, it was his mother, Elisabeth Sophie Bonicel, who took care of his education. She was a physically fragile woman, with simple manners but a strong character. She was a typical Huguenot, deeply religious and strictly faithful to her principles, driven by a strong sense of duty. On these principles, she shaped her son's character, sharing all the vicissitudes of his life. Exiled from Paris during the Revolution, they took refuge in Geneva, where Guizot was educated according to the liberal principles of Jean Jacques Rousseau. According to Rousseau's pedagogical theories in 'Emile,' the young Guizot also had to learn manual work. Thus, he learned the trade of carpenter and built a table that he always kept. However, Guizot, in his autobiography 'Memories of My Time,' omits all details of his childhood.

When Guizot was at the height of his political power, his mother, always dressed in strict mourning, was at the center of political circles. Exiled in 1848, Guizot's mother followed him to London, where she died at an advanced age. Her tomb is at Kensal Green.

At the age of 18, Guizot moved to Paris to complete his education at the law faculty. He was employed as a tutor in the house of Philippe Alfred Stapfer, a former minister of Swiss origin. He began writing for the newspaper 'Le Publiciste,' published by Jean Baptiste Suard, an activity that introduced him to Parisian literary circles. In October 1809, at 22, his theatrical critique of 'The Martyrs' by François-René de Chateaubriand earned him the author's gratitude. In the publisher's house of the newspaper, he met Pauline de Meulan, a woman fourteen years his senior: a liberal aristocrat, forced by the Revolution to earn a living through literature, and who was to write a series of articles for 'Le Publiciste.' Due to illness, she had to stop her collaboration, and the articles resumed being published by an unknown editor, who was later revealed to be Guizot himself. This collaboration with Meulan, an author of numerous works on women's education, developed into friendship and then love, leading to their marriage in 1812.

Pauline died in 1827. The couple had one child, born in 1819 and died of tuberculosis in 1837. In 1828, Guizot married Elisa Dillon, the granddaughter of his first wife and also a writer, who died in 1833, leaving a son, Maurice Guillaume (1833–1892), who gained fame as a learned intellectual and writer, and the daughters Henriette (1829–1908) and Pauline (1831–1874).

Politics

Known for his literary works, he held a chair of modern history at the Sorbonne during the Napoleonic Empire and began to be known in liberal political circles. It was during the Restoration that his political career started. Between 1826 and 1830, he published a series of works dedicated to the history of France and England, which earned him fame as a historian.

In January 1830, he was elected deputy of Lisieux and took a firm stance against King Charles X's monarchy, favoring a parliamentary constitutional regime. He supported Louis Philippe of Orleans, who, upon becoming King of the French, appointed Guizot as Minister of the Interior (1830) and later as Minister of Public Education (1832-1836), renewing its structures. During this period, he pursued a policy of strong opposition to Adolphe Thiers.

After Thiers's resignation from the government, General Soult was appointed, but it was Guizot who was the true leader (1840-1847). A supporter of peace, he achieved an alliance of reconciliation with Sir Robert Peel's England, overcoming Palmerston's opposition, who believed France should remain weak to prevent a future war. When Lord Palmerston was replaced by Lord Aberdeen, he found in Guizot a diplomat eager for peace and a lover of culture like himself, leading to the signing of an agreement between the two European liberal nations, known for the first time as the 'Entente cordiale'.

The return of Palmerston, anti-French, after the fall of Peel's government and the First Carlist War (1833-1846) shattered the Franco-British alliance and led to a shift in Guizot's foreign policy towards Austria under Metternich.

Becoming Prime Minister in 1847, on the eve of the European Revolution of 1848, he remained in power for very little time but still managed to influence the politics of his era by gathering around him a 'conservative party' that sought to maintain a balance between democratizing society and a return to revolution.

The economic policy

He strove to create the most favorable conditions for France's economic progress by primarily developing agriculture, commerce, and finance. Unlike those like Saint-Simon who advocated for the growth of the industrial system, Guizot believed that industrialization should be avoided because it involved the formation of a proletariat class that he considered unstable and politically dangerous.

Nevertheless, it was during his government that France industrialized like never before.

Her favorite was the collection of capital through the foundation of various hundreds of savings banks across the entire national territory.

There was a strong acceleration of infrastructure works such as roads, canals, and railways. In 1842, Guizot, with a law of his own, established a railway network in France that increased in six years from the initial 570 kilometers to about 1,900 kilometers.

Labor legislation was almost set aside. Industries could suppress wages and dismiss workers at will, depending on market fluctuations. Guizot made the work booklet mandatory, which workers had to present when changing jobs: this allowed employers to exclude those considered bad workers and especially agitators.

In fifteen years, iron and coal production doubled, and the number of industrial steam engines was multiplied by eight.

Political and economic ideas

Guizot was a liberal conservative in politics but opposed the principles of free trade in economics. In fact, liberalism was an English economic theory through which England promoted its interests. Conversely, French agriculture needed to be protected, and it was the industrialists themselves who pushed the government to remove tariffs.

According to Guizot, the problems France faced were not primarily economic but mainly political and social. He believed that after fifty years of wars and revolutions starting from 1789, the country was in a state of great confusion, divided between two extremes: on one side, the monarchists, nostalgic for the Ancien Régime who had never lost hope of restoring the feudal order, and on the other side, the republicans, some of whom thought they could establish a republic through revolution. He thought that liberals had the task of creating a free and peaceful society without abandoning the great achievements of the Revolution, and above all, ensuring the dominance of the bourgeoisie over the aristocracy. He viewed the French Revolution as a clash of opposing interests: the Third Estate against privileged orders, then the common people against the bourgeoisie. It was a class struggle whose outcome would permanently determine the course of history.

Fu Guizot was the first to speak of class struggle, which Marx would later theorize. He is considered the father of historiography with an economic-social approach. He believed that while the proletariat was destined to play a dominant role, workers of peasant origin should remain in the subordinate role assigned to them by society: they had lost their ties to the land, had been declassified, and therefore could not be considered responsible citizens. Drawing on the political theories of ancient Greece, he thought that democracy was a matter too serious for irresponsible individuals to have the right to voice their opinions. The right to vote should be reserved for those who owned property and paid taxes, thereby taking responsibility for their actions.

Despite his ideas about society, it should be noted that Guizot approved a law in 1841 that prohibited child labor in manufacturing for children under eight years old, and he repeatedly fought for the abolition of slavery in the colonies, succeeding in 1844 in having this principle accepted by the National Assembly. In 1845 and 1846, the issue was debated but without practically establishing the methods of emancipation. In fact, the law provided for the end of slavery but did not specify when. It was the Republicans in 1848 who ultimately determined the definitive end of slavery.

The end of Guizot's political career in 1848 was due to his stubbornness in not having the electoral law changed.

The end of his/her life

In exile in England, he once again dedicated himself to his work as a historian, focusing mainly on the themes of the French Revolution and the First English Revolution. Having lost his role as a European politician, he thus acquired the role of historian, philosopher, and observer of his time. His work as a writer allowed him to spend the last years of his life in a comfortable retreat, where he continued his work as a popularizer of history until his death on September 12, 1874.

Opere

Dictionary of French language synonyms (1809)

On the state of the fine arts in France (1810)

Annals of Education, (1811-1815, 6 vols.)

Life of French Poets of the Century of Louis XIV (1813)

Some ideas on freedom of the press (1814)

The representative government of the current state of France (1816)

Essay on the current state of public education in France (1817)

The Government of France since the Restoration. Conspiracies and Political Justice (1820)

Means of government and opposition in the current state of France. Of the government of France and the current ministry. History of the representative government in Europe, (1821, 2 vols.)

On Sovereignty (1822)

On the death penalty in political matters (1822)

Essay on the History of France from the 5th to the 10th Century (1823)

History of Charles I, (1827, 2 vols.)

General history of civilization in Europe (1828)

History of Civilization in France, (1830, 4 vols.)

The rectory by the sea (1831)

Rome and its popes (1832)

The Ministry of Reform and the Reformed Parliament (1833)

Essays on the history of France (1836)

Monk, historical study (1837)

On Religion in Modern Societies (1838)

Life, correspondence, and writings of Washington (1839–1840)

Washington (1841)

Madame de Rumfort (1842)

Political conspiracies and justice (1845)

Means of government and opposition in the current state of France in 1846.

M. Guizot and his friends. On Democracy in France (1849)

Why did the English Revolution succeed? Speech on the history of the English Revolution (1850).

Biographical studies on the English Revolution. Studies on the fine arts in general (1851).

Shakespeare and His Time. Corneille and His Time (1852)

Abélard and Héloïse (1853)

Edward III and the Bourgeois of Calais (1854)

History of the Republic of England, (1850, 2 vols. - Brussels Soc Typographique Belge Sir Robert Peel)

History of Cromwell's Protectorate and the Restoration of the Stuarts, (1856) 2 vols.

Memoirs to Serve as a History of My Time, (1858-1867, 8 vols.)

Love in Marriage (1860)

The Church and Christian Society in (1861). Academic Discourse (1861)

A royal wedding project (1862)

History of the French Parliament, collection of speeches, (1863, 5 vols. - Three generations)

Meditations on the essence of the Christian religion (1864)

William the Conqueror (1865)

Meditations on the Current State of the Christian Religion (1866)

France and Prussia responsible before Europe (1868)

Meditations on the Christian religion in its relations with the current state of societies and minds. Biographical and Literary Miscellanies (1868)

Political and Historical Essays (1869)

The history of France from the earliest times until 1789 (1870-1875, 5 vols.)

The Duke of Broglie (1872)

The Lives of Four Great French Christians (1873)

5 volumes of M. Guizot's work in 6 volumes 'Histoire de la Révolution d'Angleterre.'

The first volume of the first part of the work is missing: Histoire de Charles Ier depuis son avènement jusqu'à sa mort (1625-1649).

History of the English Revolution

Consisting of 3 parts

- History of Charles I from his accession to his death (1625-1649) (sixth edition, 1858) - Only the second volume is presented; the first volume is missing.

History of the Republic of England and Cromwell (1649-1658) (new edition, 1859) - Present the two volumes

History of the Protectorate of Richard Cromwell and the Restoration of the Stuarts 1658-1660 (new edition, 1859) - Present the two volumes

Author: François Pierre Guillaume Guizot [1787-1874]

Years: 1858-59

Publishing House: Paris - Didier et Cie, Booksellers-Publisher

Dimensions: 18.5 x 11.8 cm

Pages: 2552 total: 413 (second volume) - (VII) 524 (first volume) - 654 (second volume) - (VIII) 507 (first volume) - 439 (second volume) -

Non-editorial hardcover covers with spine ribs and titles on the back.

In good condition: good pages with browning, excellent covers (see the photos).

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot /fʁɑ̃ˈswa giˈzo/ (Nîmes, October 4, 1787 – Abbey of Val-Richer, September 12, 1874) was a French politician and historian.

Born in Nîmes to a Huguenot bourgeois family. His parents secretly married in a Catholic ceremony. On April 8, 1794, his father, Andrea Guizot, accused of federalism, was executed in Nîmes during the height of the Terror. From that moment, it was his mother, Elisabeth Sophie Bonicel, who took care of his education. She was a physically fragile woman, with simple manners but a strong character. She was a typical Huguenot, deeply religious and strictly faithful to her principles, driven by a strong sense of duty. On these principles, she shaped her son's character, sharing all the vicissitudes of his life. Exiled from Paris during the Revolution, they took refuge in Geneva, where Guizot was educated according to the liberal principles of Jean Jacques Rousseau. According to Rousseau's pedagogical theories in 'Emile,' the young Guizot also had to learn manual work. Thus, he learned the trade of carpenter and built a table that he always kept. However, Guizot, in his autobiography 'Memories of My Time,' omits all details of his childhood.

When Guizot was at the height of his political power, his mother, always dressed in strict mourning, was at the center of political circles. Exiled in 1848, Guizot's mother followed him to London, where she died at an advanced age. Her tomb is at Kensal Green.

At the age of 18, Guizot moved to Paris to complete his education at the law faculty. He was employed as a tutor in the house of Philippe Alfred Stapfer, a former minister of Swiss origin. He began writing for the newspaper 'Le Publiciste,' published by Jean Baptiste Suard, an activity that introduced him to Parisian literary circles. In October 1809, at 22, his theatrical critique of 'The Martyrs' by François-René de Chateaubriand earned him the author's gratitude. In the publisher's house of the newspaper, he met Pauline de Meulan, a woman fourteen years his senior: a liberal aristocrat, forced by the Revolution to earn a living through literature, and who was to write a series of articles for 'Le Publiciste.' Due to illness, she had to stop her collaboration, and the articles resumed being published by an unknown editor, who was later revealed to be Guizot himself. This collaboration with Meulan, an author of numerous works on women's education, developed into friendship and then love, leading to their marriage in 1812.

Pauline died in 1827. The couple had one child, born in 1819 and died of tuberculosis in 1837. In 1828, Guizot married Elisa Dillon, the granddaughter of his first wife and also a writer, who died in 1833, leaving a son, Maurice Guillaume (1833–1892), who gained fame as a learned intellectual and writer, and the daughters Henriette (1829–1908) and Pauline (1831–1874).

Politics

Known for his literary works, he held a chair of modern history at the Sorbonne during the Napoleonic Empire and began to be known in liberal political circles. It was during the Restoration that his political career started. Between 1826 and 1830, he published a series of works dedicated to the history of France and England, which earned him fame as a historian.

In January 1830, he was elected deputy of Lisieux and took a firm stance against King Charles X's monarchy, favoring a parliamentary constitutional regime. He supported Louis Philippe of Orleans, who, upon becoming King of the French, appointed Guizot as Minister of the Interior (1830) and later as Minister of Public Education (1832-1836), renewing its structures. During this period, he pursued a policy of strong opposition to Adolphe Thiers.

After Thiers's resignation from the government, General Soult was appointed, but it was Guizot who was the true leader (1840-1847). A supporter of peace, he achieved an alliance of reconciliation with Sir Robert Peel's England, overcoming Palmerston's opposition, who believed France should remain weak to prevent a future war. When Lord Palmerston was replaced by Lord Aberdeen, he found in Guizot a diplomat eager for peace and a lover of culture like himself, leading to the signing of an agreement between the two European liberal nations, known for the first time as the 'Entente cordiale'.

The return of Palmerston, anti-French, after the fall of Peel's government and the First Carlist War (1833-1846) shattered the Franco-British alliance and led to a shift in Guizot's foreign policy towards Austria under Metternich.

Becoming Prime Minister in 1847, on the eve of the European Revolution of 1848, he remained in power for very little time but still managed to influence the politics of his era by gathering around him a 'conservative party' that sought to maintain a balance between democratizing society and a return to revolution.

The economic policy

He strove to create the most favorable conditions for France's economic progress by primarily developing agriculture, commerce, and finance. Unlike those like Saint-Simon who advocated for the growth of the industrial system, Guizot believed that industrialization should be avoided because it involved the formation of a proletariat class that he considered unstable and politically dangerous.

Nevertheless, it was during his government that France industrialized like never before.

Her favorite was the collection of capital through the foundation of various hundreds of savings banks across the entire national territory.

There was a strong acceleration of infrastructure works such as roads, canals, and railways. In 1842, Guizot, with a law of his own, established a railway network in France that increased in six years from the initial 570 kilometers to about 1,900 kilometers.

Labor legislation was almost set aside. Industries could suppress wages and dismiss workers at will, depending on market fluctuations. Guizot made the work booklet mandatory, which workers had to present when changing jobs: this allowed employers to exclude those considered bad workers and especially agitators.

In fifteen years, iron and coal production doubled, and the number of industrial steam engines was multiplied by eight.

Political and economic ideas

Guizot was a liberal conservative in politics but opposed the principles of free trade in economics. In fact, liberalism was an English economic theory through which England promoted its interests. Conversely, French agriculture needed to be protected, and it was the industrialists themselves who pushed the government to remove tariffs.

According to Guizot, the problems France faced were not primarily economic but mainly political and social. He believed that after fifty years of wars and revolutions starting from 1789, the country was in a state of great confusion, divided between two extremes: on one side, the monarchists, nostalgic for the Ancien Régime who had never lost hope of restoring the feudal order, and on the other side, the republicans, some of whom thought they could establish a republic through revolution. He thought that liberals had the task of creating a free and peaceful society without abandoning the great achievements of the Revolution, and above all, ensuring the dominance of the bourgeoisie over the aristocracy. He viewed the French Revolution as a clash of opposing interests: the Third Estate against privileged orders, then the common people against the bourgeoisie. It was a class struggle whose outcome would permanently determine the course of history.

Fu Guizot was the first to speak of class struggle, which Marx would later theorize. He is considered the father of historiography with an economic-social approach. He believed that while the proletariat was destined to play a dominant role, workers of peasant origin should remain in the subordinate role assigned to them by society: they had lost their ties to the land, had been declassified, and therefore could not be considered responsible citizens. Drawing on the political theories of ancient Greece, he thought that democracy was a matter too serious for irresponsible individuals to have the right to voice their opinions. The right to vote should be reserved for those who owned property and paid taxes, thereby taking responsibility for their actions.

Despite his ideas about society, it should be noted that Guizot approved a law in 1841 that prohibited child labor in manufacturing for children under eight years old, and he repeatedly fought for the abolition of slavery in the colonies, succeeding in 1844 in having this principle accepted by the National Assembly. In 1845 and 1846, the issue was debated but without practically establishing the methods of emancipation. In fact, the law provided for the end of slavery but did not specify when. It was the Republicans in 1848 who ultimately determined the definitive end of slavery.

The end of Guizot's political career in 1848 was due to his stubbornness in not having the electoral law changed.

The end of his/her life

In exile in England, he once again dedicated himself to his work as a historian, focusing mainly on the themes of the French Revolution and the First English Revolution. Having lost his role as a European politician, he thus acquired the role of historian, philosopher, and observer of his time. His work as a writer allowed him to spend the last years of his life in a comfortable retreat, where he continued his work as a popularizer of history until his death on September 12, 1874.

Opere

Dictionary of French language synonyms (1809)

On the state of the fine arts in France (1810)

Annals of Education, (1811-1815, 6 vols.)

Life of French Poets of the Century of Louis XIV (1813)

Some ideas on freedom of the press (1814)

The representative government of the current state of France (1816)

Essay on the current state of public education in France (1817)

The Government of France since the Restoration. Conspiracies and Political Justice (1820)

Means of government and opposition in the current state of France. Of the government of France and the current ministry. History of the representative government in Europe, (1821, 2 vols.)

On Sovereignty (1822)

On the death penalty in political matters (1822)

Essay on the History of France from the 5th to the 10th Century (1823)

History of Charles I, (1827, 2 vols.)

General history of civilization in Europe (1828)

History of Civilization in France, (1830, 4 vols.)

The rectory by the sea (1831)

Rome and its popes (1832)

The Ministry of Reform and the Reformed Parliament (1833)

Essays on the history of France (1836)

Monk, historical study (1837)

On Religion in Modern Societies (1838)

Life, correspondence, and writings of Washington (1839–1840)

Washington (1841)

Madame de Rumfort (1842)

Political conspiracies and justice (1845)

Means of government and opposition in the current state of France in 1846.

M. Guizot and his friends. On Democracy in France (1849)

Why did the English Revolution succeed? Speech on the history of the English Revolution (1850).

Biographical studies on the English Revolution. Studies on the fine arts in general (1851).

Shakespeare and His Time. Corneille and His Time (1852)

Abélard and Héloïse (1853)

Edward III and the Bourgeois of Calais (1854)

History of the Republic of England, (1850, 2 vols. - Brussels Soc Typographique Belge Sir Robert Peel)

History of Cromwell's Protectorate and the Restoration of the Stuarts, (1856) 2 vols.

Memoirs to Serve as a History of My Time, (1858-1867, 8 vols.)

Love in Marriage (1860)

The Church and Christian Society in (1861). Academic Discourse (1861)

A royal wedding project (1862)

History of the French Parliament, collection of speeches, (1863, 5 vols. - Three generations)

Meditations on the essence of the Christian religion (1864)

William the Conqueror (1865)

Meditations on the Current State of the Christian Religion (1866)

France and Prussia responsible before Europe (1868)

Meditations on the Christian religion in its relations with the current state of societies and minds. Biographical and Literary Miscellanies (1868)

Political and Historical Essays (1869)

The history of France from the earliest times until 1789 (1870-1875, 5 vols.)

The Duke of Broglie (1872)

The Lives of Four Great French Christians (1873)