Karel Appel (1921-2006) - Happy Encounter

Specialises in works on paper and (New) School of Paris artists. Former gallery owner.

Catawiki Buyer Protection

Your payment’s safe with us until you receive your object.View details

Trustpilot 4.4 | 126740 reviews

Rated Excellent on Trustpilot.

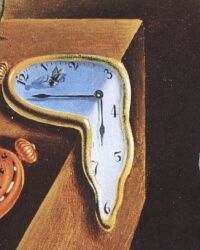

Karel Appel, Happy Encounter (1979), lithography, signed and numbered 13/160, image 80 × 60 cm, frame 107 × 87 cm, in good condition, sold with frame.

Description from the seller

Karel Appel (1921-2006)

Title: Happy Encounter

Year: 1979

Edition: 13 / 160

Technique: Lithography

Signed: signed and numbered.

Condition: Good

Image size: 80 x 60 cm inside the mat.

Frame size: 107 x 87 cm. The frame is silver-colored with a black side, 4 cm wide and 2 cm deep. The frame has minimal signs of use.

Provenance: Purchased at Reflex Modern Art Galerie in Amsterdam (purchase receipt is present, 1999).

Given the size and fragility of the work, it is preferable to pick it up from the seller in Bergen op Zoom. Hiring a courier is also an option, costs borne by the buyer. Shipping is also possible, but the risk of glass breakage lies with the buyer.

Karel Appel (Amsterdam, 25 April 1921 – Zurich, 3 May 2006) was a Dutch painter and sculptor in modern art from the second half of the twentieth century, who can be counted among the expressionists. He broke through with his membership of the Cobra group.

Biography

Appel was born on Dapperstraat in Amsterdam, in a working-class neighbourhood. As a child he was nicknamed 'Kik'. His father was the son of a milkman and owned a barber shop, where people would meet.

1940–1945 World War II

From a young age Appel knew he wanted to become a painter, but his parents preferred to see him in the barber shop. He had to work for several years with his father. In 1942 he nevertheless began studying painting at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. Discontent with this career choice, his parents put him out on the street.

Appel pursued this training up to 1944. At the academy he learned about art history, of which he had little exposure at home. He trained in traditional drawing and painting. To make his studies possible, Appel received a grant from the Department of Public Information and the Arts (DVK). To obtain that grant, Appel regularly contacted the National Socialist Ed Gerdes, head of the Department of Architecture, Visual Arts and Applied Arts of the Department of Public Information and the Arts, to whom he often asked for additional support, which he did not always receive.

In retrospect, Appel was accused of going to study during the German occupation, while the Germans in their own country pursued a very repressive policy against the so-called Entartete Kunst and, in the Netherlands, mainly against artists of Jewish descent. Appel himself stated that he had never collaborated with the Germans; he did indeed want a grant, but otherwise had only attended the academy to learn to paint well. Appel therefore did not feel connected to the Germans. Art was a matter of the heart, and political preferences interested him little. Other artists during the war were more principled and, for example, refused to join the Kultuurkamer, which meant they could not work, sell, and had to live without income.

During his time at the Rijksakademie, Appel met Corneille. A little later he became acquainted with Constant. An intense friendship developed between them that would endure for many years. With Constant, Appel undertook trips after the war to Liège and Paris. The two exhibited together.

At the beginning of the Hunger Winter, Appel fled his home—he no longer lived with his parents—out of fear of being arrested by the German occupiers because of his refusal to work in Germany. During the winter he wandered across the Netherlands, heading toward his brother who lived near Hengelo. Painting was hardly possible during that period, although he did draw a few portraits of starving people.

After the war Appel returned weakened to Amsterdam, where he had a short relationship with Truusje, who, however, soon died of tuberculosis. There were few people who saw anything in Appel at that time. The exceptions were the art critic H. Klinkenberg, who wrote a positive article about Appel, and the wealthy Liège collector Ernest van Zuylen, who bought Appel’s art annually.

1946–1956 Cobra

In 1946 Appel had his first solo exhibition at Het Beerenhuis in Groningen. Some time later, he took part in the exhibition Jonge Schilders at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. During this period he was particularly influenced by the art of Picasso, Matisse, and Jean Dubuffet. In particular, the latter made raw works using materials other than paint.

Appel began sculpting in 1947, after consulting sculptor Carel Kneulman about it. Appel's contemporaries, however, did not call his works sculptures. Appel collected all kinds of junk, even dismantled the wooden shutters of his windows and the hook of the hoist beam in his attic room. From that wood, a broom handle, and a vacuum cleaner hose, he made the work Drift on the Attic. With red and black paint, he laid on the form of a head and eyes. During this period, Appel lived with Tony Sluyter.

On July 16, 1948, the artists Karel Appel, Corneille and Constant together with Anton Rooskens, Theo Wolvecamp, who called himself Theo Wolvé, and Jan Nieuwenhuys, Constant’s brother, founded the Experimental Group in Holland. Tjeerd Hansma was also involved in the founding, but this rogue and tough guy left the group. The Belgian writer Hugo Claus joined later.

The first publication of the group contained a strongly left-oriented manifesto by Constant. Appel didn’t feel he belonged to it; it was about art alone—“l'art pour l'art.” When Appel created a series of paintings called Kampong Blood, in response to the Netherlands’ police actions in Indonesia, it was to him more about the human indignation at the suffering of the individual than about disseminating a Marxist stance.

In November 1948, several members of the Experimental Group attended an international conference on avant-garde art in Paris, organized by French and Belgian surrealist colleagues. Constant read there a translation of his manifesto, which, however, did not resonate with the audience.

Among others, the Belgian Christian Dotremont found the French approach too sectarian. Some Danish, Dutch and Belgian artists withdrew from the congress as a result and formed the Cobra group. 'CoBrA' is an abbreviation of Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam. Meanwhile, the work of the Experimentele Groep in the Netherlands was poorly received.

A Christian monthly magazine, "Op den uitkijk", wrote that they would do better to pave Kalverstraat with their works, or throw the work into the IJ, rather than bring it before the eyes of the respectable bourgeois Dutch people.

Nevertheless De Bijenkorf exhibited the work of Appel, Corneille and Constant, where, among others, the architect Aldo van Eyck came under scrutiny.

The director of the Stedelijk Museum, Willem Sandberg, however (still) had "no room" to exhibit art by the Experimentele Groep.

In Denmark, Cobra's work was warmly received by the press.

When Appel traveled to Copenhagen, he enjoyed there the congenial atmosphere.

To the astonishment of the members, Cobra nevertheless received an exhibition in 1949 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The exhibition became a scandal. Disappointed by this, Appel settled in Paris in 1950. He later said that the constant swearing had driven him out of the Netherlands. The same exhibition as in the Stedelijk Museum was subsequently shown in Paris and was received much better there than in Amsterdam.

In Paris, Hugo Claus introduced Appel to Michel Tapié, who subsequently organized several exhibitions of Appel's work. Thus, Appel received a solo exhibition in 1953 at the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels. In 1954 he received the UNESCO Prize at the Venice Biennale.

Appell was still not accepted in the Netherlands. He did, however, receive a commission from the municipality of Amsterdam to create a wall painting for the cantine of the city hall (the current hotel The Grand), but this led to a scandal. After protests by the civil servants, the work, titled 'Vragende kinderen', at the time called 'Twistappel', was covered behind wallpaper for ten years. The civil servants found the painting barbaric, cruel, and violent.

At the end of 1950, Appel and Hugo Claus together produced a set of illustrated poems, The Joyful and Unforeseen Week, which people could receive through pre-order. There turned out to be only three subscribers. The booklet appeared in 200 copies, copied, and hand-colored. Claus wrote about this in 1968: "It was our policy to make such a booklet in one afternoon. With a tiny bit of encouragement we had then produced fifty per year." But that encouragement proved insufficient given the number of subscribers. A copy of this edition is one of the highlights of the Special Collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague.

After the dissolution of Cobra, Karel Appel began painting with increasingly thick paint, impasto. His work grew increasingly wilder and seemingly less controlled.

Appel's international breakthrough began around 1953, when his work was shown at the São Paulo Biennial. In 1954 there were solo exhibitions of Appel in Paris and New York. He created numerous murals for public buildings. In 1955 he made an 80-meter-long mural for the National Energy Manifestation 1955.

1957–2006: International breakthrough

From 1957, Appel regularly traveled to New York. There he painted, among other things, portraits of jazz musicians. He developed his own style, independent of others. During this period he moved increasingly toward abstract art, although he continued to deny it himself. The title of a work such as Composition does seem to point to that.

In the late 1960s, Appel moved to the Château de Molesmes, near Auxerre. In the meantime, Appel was increasingly internationally acclaimed. In 1968 there was also a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Exhibitions followed at the Kunsthalle in Basel, in Brussels (1969), and at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht (1970). A traveling exhibition through Canada and the United States followed in 1972.

Around 1990 Appel had four studios, in New York, Connecticut, Monaco, and Mercatale Valdarno (Tuscany). He mainly used the New York studio to experiment with his painting. He developed the New York experiments in his other studios. The different light, for instance in Tuscany, gave rise there to works on the same themes with a wholly distinctive character.

On the occasion of an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, he told Rudi Fuchs, then-director of the museum, about his work. Before he began, he looked at the canvas for a long time, but once he started painting, he could hardly restrain his impulses to apply paint. He gave the impression of working like a man possessed, though he took a lot of time to mix the paint to the right color. When the canvas was almost finished, he worked more slowly; finally he would add only a single brushstroke or even omit the last refinements. Appel always worked on one painting at a time.

Just before his death in 2006, Appel completed a postage stamp for TPG Post. The 39-cent stamp appeared in September 2006 on the occasion of an exhibition about visual artists and stamps titled Kunst om te versturen.

Karel Appel was buried in a private ceremony at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Statements

Appel made many pithy, quotable statements that, for the general public in the years after World War II, provoked the necessary resistance:

• I’m making a bit of a mess. These days I lay it on thick, I fling the paint at it with brushes and putty knives and bare hands, I sometimes throw whole pots at it at once. To the Vrij Nederland magazine in response to the film by Jan Vrijman.

This statement in Bargoens gave rise to the creation of the verb 'aanappelen', meaning 'to act with indifferent caprice' or 'just do something'. The word probably fell out of use later when Appel was generally accepted as an artist. [2]

• I paint like a barbarian in this barbaric age.

• I have, over the years, learned how to apply oil paint to canvas. I can now do anything with paint that I want. But it is still a struggle, still a fight. At the moment I am still in the chaos. But it is simply my nature to make the chaos positive. That is the spirit of our time today. We always live in a terrible chaos, and who can still make the chaos positive? Only the artist. Monaco, 1986.

• Shut up and be pretty. Keep your mouth shut and be nice to Sonja Barend.

• I also use more paint!!, after Appel had stashed a large part of the revenues from a Cobra group exhibition in his own pocket.

The painting style of Karel Appel

Appel, in his own words, never painted abstractly, although his work comes close to that. There are always recognizable figures to be discovered: people, animals, or, for example, suns.

During the Cobra period, from 1948 onward, Appel painted simple shapes with strong contour lines, filled in with vivid colors.

His work belongs to modern art, and the painting style is Abstract Expressionism.

Subjects were friendly, innocent, childlike beings and fantasy animals. He was influenced by the way people with intellectual disabilities draw and paint, something that at the time could be called revolutionary. Appel's work prompted remarks such as, "I can do that too." The style of child drawings was supplemented by Appel with the style of African masks.

Later Appel loosened the coherence between form and color. He worked mostly with black outlines to indicate figures. Often he used unmixed paint for those contours, squeezed straight from the tube. But he seemed to pay little heed to the contours, with the color he applied to give the figures their form. The colors spread beyond the outlines, and the background color often intrudes into the figure.

According to art historian Willemijn Stokvis, Appel, in his painting career, has plunged wholeheartedly into the paint, to utter a primal scream there. This approach is completely opposite to the working method of Appel’s world-famous Dutch contemporary Mondrian. “Both represent two poles of the history of modern art, in which they relate to each other as the utmost mastery to eruptive spontaneity. Both sought the primal source of creation, a quest that perhaps forms the basis for a large part of modern art. Mondrian sought the primal formula on which the construction of the cosmos rests; of Appel one can say that he tried to wake the creative drive within himself with which that universe would have been made,” according to Willemijn Stokvis.

Appel's work is usually built up in multiple layers, giving it depth and relief. On a nearly monochrome, yet carefully painted ground, he painted his subjects in at least two stages. According to his own words, he often turned the work upside down or looked at it between his legs. This is a well-known method of checking whether a work's composition is balanced.

Appel often created several versions in response to the same theme. For example, he produced various works with the title of the controversial mural in Amsterdam, Vragende kinderen. Those were not only paintings, but also artworks consisting of a wooden relief, painted in primary and secondary colors. Appel kept making series on the same theme throughout his life. At the end of the 1970s, for example, he created a series Gezicht in landschap, through which he wanted to express that humans and nature form a unity.

Appels' drive comes through in his statement:

A life without inspiration is, to me, the absolute lowest, the most base thing there is.

Karel Appel (1921-2006)

Title: Happy Encounter

Year: 1979

Edition: 13 / 160

Technique: Lithography

Signed: signed and numbered.

Condition: Good

Image size: 80 x 60 cm inside the mat.

Frame size: 107 x 87 cm. The frame is silver-colored with a black side, 4 cm wide and 2 cm deep. The frame has minimal signs of use.

Provenance: Purchased at Reflex Modern Art Galerie in Amsterdam (purchase receipt is present, 1999).

Given the size and fragility of the work, it is preferable to pick it up from the seller in Bergen op Zoom. Hiring a courier is also an option, costs borne by the buyer. Shipping is also possible, but the risk of glass breakage lies with the buyer.

Karel Appel (Amsterdam, 25 April 1921 – Zurich, 3 May 2006) was a Dutch painter and sculptor in modern art from the second half of the twentieth century, who can be counted among the expressionists. He broke through with his membership of the Cobra group.

Biography

Appel was born on Dapperstraat in Amsterdam, in a working-class neighbourhood. As a child he was nicknamed 'Kik'. His father was the son of a milkman and owned a barber shop, where people would meet.

1940–1945 World War II

From a young age Appel knew he wanted to become a painter, but his parents preferred to see him in the barber shop. He had to work for several years with his father. In 1942 he nevertheless began studying painting at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. Discontent with this career choice, his parents put him out on the street.

Appel pursued this training up to 1944. At the academy he learned about art history, of which he had little exposure at home. He trained in traditional drawing and painting. To make his studies possible, Appel received a grant from the Department of Public Information and the Arts (DVK). To obtain that grant, Appel regularly contacted the National Socialist Ed Gerdes, head of the Department of Architecture, Visual Arts and Applied Arts of the Department of Public Information and the Arts, to whom he often asked for additional support, which he did not always receive.

In retrospect, Appel was accused of going to study during the German occupation, while the Germans in their own country pursued a very repressive policy against the so-called Entartete Kunst and, in the Netherlands, mainly against artists of Jewish descent. Appel himself stated that he had never collaborated with the Germans; he did indeed want a grant, but otherwise had only attended the academy to learn to paint well. Appel therefore did not feel connected to the Germans. Art was a matter of the heart, and political preferences interested him little. Other artists during the war were more principled and, for example, refused to join the Kultuurkamer, which meant they could not work, sell, and had to live without income.

During his time at the Rijksakademie, Appel met Corneille. A little later he became acquainted with Constant. An intense friendship developed between them that would endure for many years. With Constant, Appel undertook trips after the war to Liège and Paris. The two exhibited together.

At the beginning of the Hunger Winter, Appel fled his home—he no longer lived with his parents—out of fear of being arrested by the German occupiers because of his refusal to work in Germany. During the winter he wandered across the Netherlands, heading toward his brother who lived near Hengelo. Painting was hardly possible during that period, although he did draw a few portraits of starving people.

After the war Appel returned weakened to Amsterdam, where he had a short relationship with Truusje, who, however, soon died of tuberculosis. There were few people who saw anything in Appel at that time. The exceptions were the art critic H. Klinkenberg, who wrote a positive article about Appel, and the wealthy Liège collector Ernest van Zuylen, who bought Appel’s art annually.

1946–1956 Cobra

In 1946 Appel had his first solo exhibition at Het Beerenhuis in Groningen. Some time later, he took part in the exhibition Jonge Schilders at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. During this period he was particularly influenced by the art of Picasso, Matisse, and Jean Dubuffet. In particular, the latter made raw works using materials other than paint.

Appel began sculpting in 1947, after consulting sculptor Carel Kneulman about it. Appel's contemporaries, however, did not call his works sculptures. Appel collected all kinds of junk, even dismantled the wooden shutters of his windows and the hook of the hoist beam in his attic room. From that wood, a broom handle, and a vacuum cleaner hose, he made the work Drift on the Attic. With red and black paint, he laid on the form of a head and eyes. During this period, Appel lived with Tony Sluyter.

On July 16, 1948, the artists Karel Appel, Corneille and Constant together with Anton Rooskens, Theo Wolvecamp, who called himself Theo Wolvé, and Jan Nieuwenhuys, Constant’s brother, founded the Experimental Group in Holland. Tjeerd Hansma was also involved in the founding, but this rogue and tough guy left the group. The Belgian writer Hugo Claus joined later.

The first publication of the group contained a strongly left-oriented manifesto by Constant. Appel didn’t feel he belonged to it; it was about art alone—“l'art pour l'art.” When Appel created a series of paintings called Kampong Blood, in response to the Netherlands’ police actions in Indonesia, it was to him more about the human indignation at the suffering of the individual than about disseminating a Marxist stance.

In November 1948, several members of the Experimental Group attended an international conference on avant-garde art in Paris, organized by French and Belgian surrealist colleagues. Constant read there a translation of his manifesto, which, however, did not resonate with the audience.

Among others, the Belgian Christian Dotremont found the French approach too sectarian. Some Danish, Dutch and Belgian artists withdrew from the congress as a result and formed the Cobra group. 'CoBrA' is an abbreviation of Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam. Meanwhile, the work of the Experimentele Groep in the Netherlands was poorly received.

A Christian monthly magazine, "Op den uitkijk", wrote that they would do better to pave Kalverstraat with their works, or throw the work into the IJ, rather than bring it before the eyes of the respectable bourgeois Dutch people.

Nevertheless De Bijenkorf exhibited the work of Appel, Corneille and Constant, where, among others, the architect Aldo van Eyck came under scrutiny.

The director of the Stedelijk Museum, Willem Sandberg, however (still) had "no room" to exhibit art by the Experimentele Groep.

In Denmark, Cobra's work was warmly received by the press.

When Appel traveled to Copenhagen, he enjoyed there the congenial atmosphere.

To the astonishment of the members, Cobra nevertheless received an exhibition in 1949 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The exhibition became a scandal. Disappointed by this, Appel settled in Paris in 1950. He later said that the constant swearing had driven him out of the Netherlands. The same exhibition as in the Stedelijk Museum was subsequently shown in Paris and was received much better there than in Amsterdam.

In Paris, Hugo Claus introduced Appel to Michel Tapié, who subsequently organized several exhibitions of Appel's work. Thus, Appel received a solo exhibition in 1953 at the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels. In 1954 he received the UNESCO Prize at the Venice Biennale.

Appell was still not accepted in the Netherlands. He did, however, receive a commission from the municipality of Amsterdam to create a wall painting for the cantine of the city hall (the current hotel The Grand), but this led to a scandal. After protests by the civil servants, the work, titled 'Vragende kinderen', at the time called 'Twistappel', was covered behind wallpaper for ten years. The civil servants found the painting barbaric, cruel, and violent.

At the end of 1950, Appel and Hugo Claus together produced a set of illustrated poems, The Joyful and Unforeseen Week, which people could receive through pre-order. There turned out to be only three subscribers. The booklet appeared in 200 copies, copied, and hand-colored. Claus wrote about this in 1968: "It was our policy to make such a booklet in one afternoon. With a tiny bit of encouragement we had then produced fifty per year." But that encouragement proved insufficient given the number of subscribers. A copy of this edition is one of the highlights of the Special Collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague.

After the dissolution of Cobra, Karel Appel began painting with increasingly thick paint, impasto. His work grew increasingly wilder and seemingly less controlled.

Appel's international breakthrough began around 1953, when his work was shown at the São Paulo Biennial. In 1954 there were solo exhibitions of Appel in Paris and New York. He created numerous murals for public buildings. In 1955 he made an 80-meter-long mural for the National Energy Manifestation 1955.

1957–2006: International breakthrough

From 1957, Appel regularly traveled to New York. There he painted, among other things, portraits of jazz musicians. He developed his own style, independent of others. During this period he moved increasingly toward abstract art, although he continued to deny it himself. The title of a work such as Composition does seem to point to that.

In the late 1960s, Appel moved to the Château de Molesmes, near Auxerre. In the meantime, Appel was increasingly internationally acclaimed. In 1968 there was also a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Exhibitions followed at the Kunsthalle in Basel, in Brussels (1969), and at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht (1970). A traveling exhibition through Canada and the United States followed in 1972.

Around 1990 Appel had four studios, in New York, Connecticut, Monaco, and Mercatale Valdarno (Tuscany). He mainly used the New York studio to experiment with his painting. He developed the New York experiments in his other studios. The different light, for instance in Tuscany, gave rise there to works on the same themes with a wholly distinctive character.

On the occasion of an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, he told Rudi Fuchs, then-director of the museum, about his work. Before he began, he looked at the canvas for a long time, but once he started painting, he could hardly restrain his impulses to apply paint. He gave the impression of working like a man possessed, though he took a lot of time to mix the paint to the right color. When the canvas was almost finished, he worked more slowly; finally he would add only a single brushstroke or even omit the last refinements. Appel always worked on one painting at a time.

Just before his death in 2006, Appel completed a postage stamp for TPG Post. The 39-cent stamp appeared in September 2006 on the occasion of an exhibition about visual artists and stamps titled Kunst om te versturen.

Karel Appel was buried in a private ceremony at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Statements

Appel made many pithy, quotable statements that, for the general public in the years after World War II, provoked the necessary resistance:

• I’m making a bit of a mess. These days I lay it on thick, I fling the paint at it with brushes and putty knives and bare hands, I sometimes throw whole pots at it at once. To the Vrij Nederland magazine in response to the film by Jan Vrijman.

This statement in Bargoens gave rise to the creation of the verb 'aanappelen', meaning 'to act with indifferent caprice' or 'just do something'. The word probably fell out of use later when Appel was generally accepted as an artist. [2]

• I paint like a barbarian in this barbaric age.

• I have, over the years, learned how to apply oil paint to canvas. I can now do anything with paint that I want. But it is still a struggle, still a fight. At the moment I am still in the chaos. But it is simply my nature to make the chaos positive. That is the spirit of our time today. We always live in a terrible chaos, and who can still make the chaos positive? Only the artist. Monaco, 1986.

• Shut up and be pretty. Keep your mouth shut and be nice to Sonja Barend.

• I also use more paint!!, after Appel had stashed a large part of the revenues from a Cobra group exhibition in his own pocket.

The painting style of Karel Appel

Appel, in his own words, never painted abstractly, although his work comes close to that. There are always recognizable figures to be discovered: people, animals, or, for example, suns.

During the Cobra period, from 1948 onward, Appel painted simple shapes with strong contour lines, filled in with vivid colors.

His work belongs to modern art, and the painting style is Abstract Expressionism.

Subjects were friendly, innocent, childlike beings and fantasy animals. He was influenced by the way people with intellectual disabilities draw and paint, something that at the time could be called revolutionary. Appel's work prompted remarks such as, "I can do that too." The style of child drawings was supplemented by Appel with the style of African masks.

Later Appel loosened the coherence between form and color. He worked mostly with black outlines to indicate figures. Often he used unmixed paint for those contours, squeezed straight from the tube. But he seemed to pay little heed to the contours, with the color he applied to give the figures their form. The colors spread beyond the outlines, and the background color often intrudes into the figure.

According to art historian Willemijn Stokvis, Appel, in his painting career, has plunged wholeheartedly into the paint, to utter a primal scream there. This approach is completely opposite to the working method of Appel’s world-famous Dutch contemporary Mondrian. “Both represent two poles of the history of modern art, in which they relate to each other as the utmost mastery to eruptive spontaneity. Both sought the primal source of creation, a quest that perhaps forms the basis for a large part of modern art. Mondrian sought the primal formula on which the construction of the cosmos rests; of Appel one can say that he tried to wake the creative drive within himself with which that universe would have been made,” according to Willemijn Stokvis.

Appel's work is usually built up in multiple layers, giving it depth and relief. On a nearly monochrome, yet carefully painted ground, he painted his subjects in at least two stages. According to his own words, he often turned the work upside down or looked at it between his legs. This is a well-known method of checking whether a work's composition is balanced.

Appel often created several versions in response to the same theme. For example, he produced various works with the title of the controversial mural in Amsterdam, Vragende kinderen. Those were not only paintings, but also artworks consisting of a wooden relief, painted in primary and secondary colors. Appel kept making series on the same theme throughout his life. At the end of the 1970s, for example, he created a series Gezicht in landschap, through which he wanted to express that humans and nature form a unity.

Appels' drive comes through in his statement:

A life without inspiration is, to me, the absolute lowest, the most base thing there is.