No. 100039108

Gio Ponti - Lo Stile - 1942

No. 100039108

Gio Ponti - Lo Stile - 1942

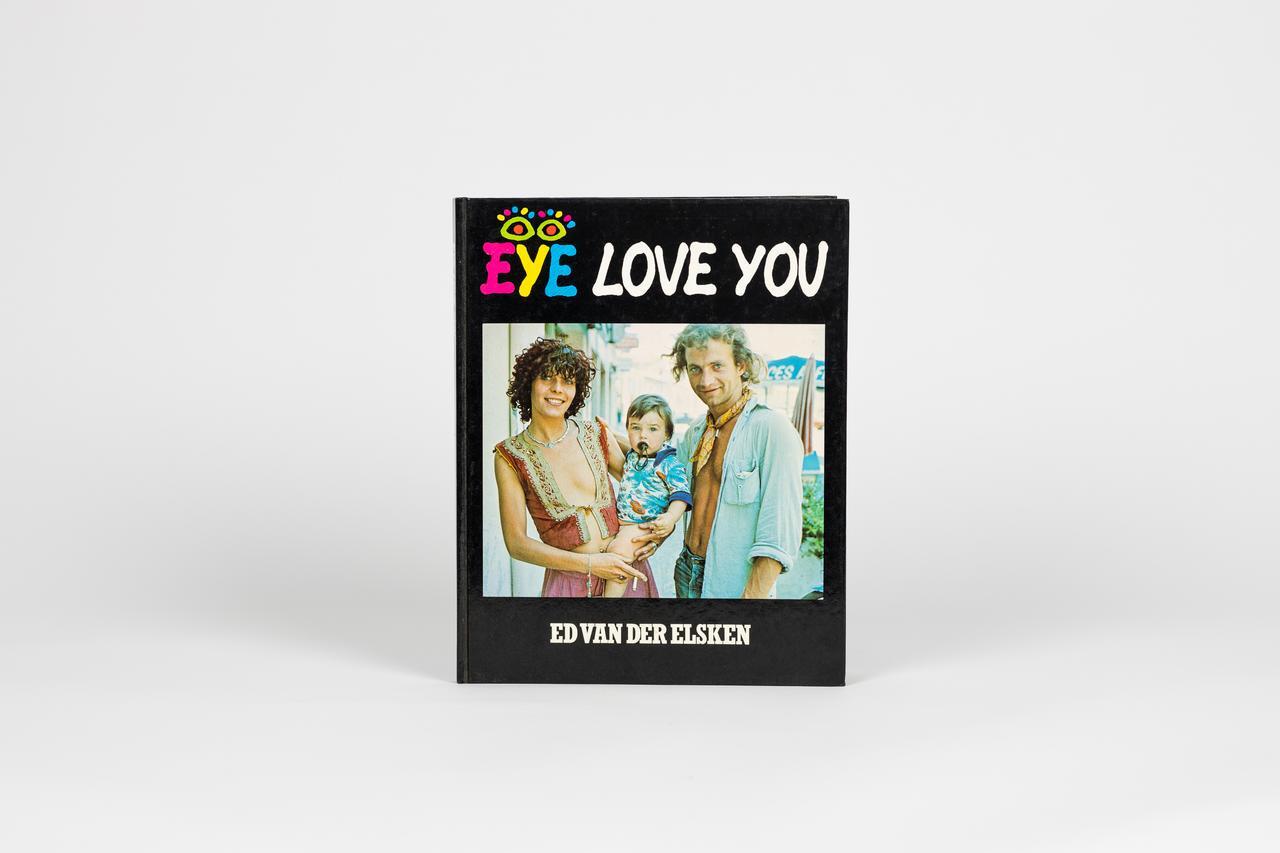

Gio Ponti. Lo Stile nella casa e nell'arredamento, n.13/1942. Milano, Garzanti, 1942. Copertina firmata con l'acronimo ‘Gienlica’, (Gio Ponti, Enrico Bo, Lina Bo, Carlo Pagani). Dimensione 32,5x24,5 cm. Brossura editoriale, pagine numerate 59. Illustrazioni e disegni in bianco e nero. In questo numero: Giorgio De Chirico, Considerazioni sulla pittura moderna; Gio Ponti, Opere durature agli artisti non premi ed esposizioni; Un arredamento dell'architetto Franco Buzzi; Gio Ponti, Disegni di Mobili; De Pisis in casa; ecc. ecc. In buono stato - qualche abrasione al dorso e normali segni del tempo.

'Stile', un'indicazione di opere d'architettura e d'arredamento, e anche di disegni, e di opere di pittura e di scultura". Sotto l’egida d’una parola altamente impegnativa, ‘Stile’, si inizia una indicazione di opere d’architettura e d’arredamento, e anche di disegni, e di opere di pittura e di scultura”. Così scrive Gio Ponti, nel gennaio 1941, nel primo numero di “Stile”, la rivista “di idee, di vita, d’avvenire, e soprattutto d’arte” da lui creata e diretta per le edizioni Garzanti, dopo aver lasciato l’Editoriale Domus. “Lo Stile nella casa e nell’arredamento” come recita inizialmente il titolo completo della rivista – viene pubblicato con cadenza mensile per tutta la durata della guerra, e prosegue fino al 1947, quando, dopo oltre settanta numeri, Ponti riprende le trattative con Gianni Mazzocchi per ritornare alla direzione di “Domus”. In questi sei anni “Stile”, è la rivista di Ponti, la sua “creatura”: egli ne è l’ideatore e il direttore, ma anche il redattore e l’impaginatore; ne disegna numerose copertine, “a dire con arte il suo pensiero” e firma, con il suo nome o con uno dei suoi vari pseudonimi (Archias, Artifex, Mitus, Serangelo, Tipus, ecc.), oltre quattrocento articoli, tra editoriali, note e corsivi.

Giovanni Ponti, detto Gio[1] (Milano, 18 novembre 1891 – Milano, 16 settembre 1979), è stato un architetto e designer italiano fra i più importanti del dopoguerra[1].

Biografia

«Gli italiani sono nati per costruire. Costruire è carattere della loro razza, forma della loro mente, vocazione ed impegno del loro destino, espressione della loro esistenza, segno supremo ed immortale della loro storia.»

(Gio Ponti, Vocazione architettonica degli italiani, 1940)

Figlio di Enrico Ponti e di Giovanna Rigone, Gio Ponti si laureò in architettura presso l'allora Regio Istituto Tecnico Superiore (il futuro Politecnico di Milano) nel 1921, dopo aver sospeso gli studi durante la sua partecipazione alla prima guerra mondiale. Nello stesso anno si sposò con la nobile Giulia Vimercati, di antica famiglia brianzola, da cui ebbe quattro figli (Lisa, Giovanna, Letizia e Giulio)[2].

Anni venti e trenta

Casa Marmont a Milano, 1934

Il palazzo Montecatini a Milano, 1938

Inizialmente, nel 1921, aprì uno studio assieme gli architetti Mino Fiocchi ed Emilio Lancia (1926-1933), per poi passare alla collaborazione con gli ingegneri Antonio Fornaroli ed Eugenio Soncini (1933-1945). Nel 1923 partecipò alla I Biennale delle arti decorative tenutasi all'ISIA di Monza e successivamente fu coinvolto nella organizzazione delle varie Triennali, sia a Monza che a Milano.

Negli anni venti avviò la sua attività di designer all'industria ceramica Richard-Ginori, rielaborando complessivamente la strategia di disegno industriale della società; con le sue ceramiche vinse il "Grand Prix" all'Esposizione internazionale di arti decorative e industriali moderne di Parigi del 1925[3]. In quegli anni, la sua produzione fu improntata più ai temi classici reinterpretati in chiave déco, mostrandosi più vicino al movimento Novecento, esponente del razionalismo[4]. Sempre negli stessi anni iniziò anche la sua attività editoriale: nel 1928 fondò la rivista Domus, testata che diresse fino alla sua morte, eccetto che nel periodo 1941-1948 in cui fu direttore di Stile[4]. Assieme a Casabella, Domus rappresenterà il centro del dibattito culturale dell'architettura e del design italiani della seconda metà del Novecento[5].

Servizio da caffè "Barbara" disegnato da Ponti per Richard Ginori nel 1930

L'attività di Ponti negli anni trenta si estese all'organizzazione della V Triennale di Milano (1933) e alla realizzazione di scene e costumi per il Teatro alla Scala[6]. Partecipò all'Associazione del Disegno Industriale (ADI) e fu tra i sostenitori del premio Compasso d'oro, promosso dai magazzini La Rinascente[7]. Ricevette tra l'altro numerosi premi sia nazionali che internazionali, diventando infine professore di ruolo alla Facoltà di Architettura del Politecnico di Milano nel 1936, cattedra che manterrà sino al 1961[senza fonte]. Nel 1934 l'Accademia d'Italia gli conferì il "premio Mussolini" per le arti[8].

Nel 1937 incaricò Giuseppe Cesetti di eseguire un pavimento in ceramica di vaste dimensioni, esposto alla Mostra Universale di Parigi, in una sala dove erano anche opere di Gino Severini e Massimo Campigli.

Anni quaranta e cinquanta

Nel 1941, durante la seconda guerra mondiale, Ponti fonda la rivista di architettura e design del regime fascista STILE. Nella rivista di chiaro supporto all'asse Roma-Berlino, Ponti non manca di scrivere nei suoi editoriali commenti come "Nel dopoguerra spettano all'Italia compiti grandissimi ...nei rapporti della sua esemplare alleata, la Germania", "i nostri grandi alleati [Germania nazista] ci danno un esempio di applicazione tenace, serissima, organizzata e ordinata" (da Stile, Agosto 1941, pag. 3). Stile durerà pochi anni e chiuderà dopo l'Invasione d'Italia anglo-americana e la sconfitta dell'Asse Italo-tedesco. Nel 1948, Ponti riapre la rivista Domus, dove rimarrà come editore fino alla sua morte.

Nel 1951, si unì allo studio insieme a Fornaroli, l'architetto Alberto Rosselli[9]. Nel 1952 costituisce con l'architetto Alberto Rosselli lo studio Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli[10]. Qui iniziò il periodo di più intensa e feconda attività sia nell'architettura che nel design, abbandonando i frequenti riallacci al passato neoclassico e puntando su idee più innovative.

Anni sessanta e settanta

Fra il 1966 ed il 1968 collaborò con l'impresa di produzione Ceramica Franco Pozzi di Gallarate[senza fonte].

Il Centro Studi e Archivio della Comunicazione di Parma conserva un Fondo dedicato a Gio Ponti, consistente in 16.512 schizzi e disegni, 73 plastici e maquettes. L'archivio Ponti[10] è stato donato dagli eredi dell'architetto (donatori Anna Giovanna Ponti, Letizia Ponti, Salvatore Licitra, Matteo Licitra, Giulio Ponti) nel 1982. Questo fondo, il cui materiale progettuale documenta le opere realizzate dal designer milanese dagli anni Venti agli anni Settanta, è pubblico e consultabile.

Gio Ponti morì a Milano nel 1979: riposa al cimitero monumentale di Milano[11]. Il suo nome ha meritato l'iscrizione al famedio del medesimo cimitero[12].

Stile

Gio Ponti ha disegnato moltissimi oggetti nei più svariati campi, dalle scenografie teatrali, alle lampade, alle sedie, agli oggetti da cucina, agli interni di transatlantici[13]. Inizialmente nell'arte delle ceramiche il suo disegno rifletteva la Secessione viennese[senza fonte] e sosteneva che decorazione tradizionale e arte moderna non fossero incompatibili. Il suo riallacciarsi e utilizzare i valori del passato trovò sostenitori nel regime fascista, incline alla salvaguardia della "identità italiana" e al recupero degli ideali della "romanità",[senza fonte] che si espresse poi compiutamente in architettura con il neoclassicismo semplificato del Piacentini.

Macchina da caffè La Pavoni, progettata da Ponti nel 1948

Nel 1950 Ponti cominciò a impegnarsi nella progettazione di "pareti attrezzate", ovvero intere pareti prefabbricate che permettevano di soddisfare diversi bisogni, integrando in un unico sistema apparecchi e attrezzature fino ad allora autonome. Ricordiamo Ponti anche per il progetto della seduta "Superleggera" del 1955 (prod. Cassina)[14], realizzata partendo da un oggetto già esistente e di solito prodotto artigianalmente: la Sedia di Chiavari[15], migliorato in materiali e prestazioni.

Nonostante questo, Ponti realizzerà nella Città universitaria di Roma nel 1934 la Scuola di Matematica[16] (una delle prime opere del Razionalismo italiano) e nel 1936 il primo degli edifici per uffici della Montecatini a Milano. Quest'ultimo, a caratteri fortemente personali, risente nei particolari architettonici, di ricercata eleganza, della vocazione di designer del progettista.

Negli anni cinquanta, lo stile di Ponti si fece più innovativo[17] e, pur rimanendo classicheggiante nel secondo palazzo per uffici della Montecatini (1951), si espresse pienamente nel suo edificio più significativo: il Grattacielo Pirelli in Piazza Duca d'Aosta a Milano (1955-1958)[18]. L'opera fu costruita intorno a una struttura centrale progettata da Nervi (127,1 metri). L'edificio appare come una slanciata e armoniosa lastra di cristallo[19], che taglia lo spazio architettonico del cielo, disegnata su un equilibrato curtain wall e i cui lati lunghi si restringono in quasi due linee verticali. Quest'opera anche con il suo carattere di "eccellenza" appartiene a buon diritto al Movimento Moderno in Italia[20].

Opere

Industrial design

1923-1929 Porcellane per Richard-Ginori

1927 Oggetti in peltro ed argento per Christofle

1930 Grandi pezzi in cristallo per Fontana

1930 Grande tavolo in alluminio presentato alla IV Triennale di Monza

1930 Disegni per stoffe stampate per De Angeli-Frua, Milano

1930 Tessuti per Vittorio Ferrari

1930 Posate ed altri oggetti per Krupp Italiana

1931 Lampade per Fontana, Milano

1931 Tre librerie per le Opera Omnia di D'Annunzio

1931 Mobili per Turri, Varedo (Milano)

1934 Arredamento Brustio, Milano

1935 Arredamento Cellina, Milano

1936 Arredamento Piccoli, Milano

1936 Arredamento Pozzi, Milano

1936 Orologi per Boselli, Milano

1936 Sedia a volute presentata alla VI Triennale di Milano prodotta da Casa e Giardino, poi (1946) Cassina e (1969) Montina

1936 Mobili per Casa e Giardino, Milano

1938 Tessuti per Vittorio Ferrari, Milano

1938 Poltrone per Casa e Giardino

1938 Seduta girevole in acciaio per Kardex

1947 Interni del Treno Settebello

1948 Collabora con Alberto Rosselli e Antonio Fornaroli alla creazione de "La Cornuta", la prima macchina da caffè espresso a caldaia orizzontale prodotta da "La Pavoni S.p.A."

1949 Collabora con officine meccaniche Visa di Voghera e crea la macchina da cucire "Visetta".

1952 Collabora con AVE, creazione di interruttori elettrici

1955 Posate per Arthur Krupp

1957 Sedia Superleggera per Cassina

1963 Scooter Brio per Ducati

1971 Poltrona di poco sedile per Walter Ponti

Luigi Filippo Tibertelli, semplicemente conosciuto come Filippo de Pisis (Ferrara, 11 maggio 1896 – Milano, 2 aprile 1956), è stato un pittore e scrittore italiano, uno tra i maggiori interpreti della pittura italiana della prima metà del Novecento.

Biografia

Filippo de Pisis all'età di diciotto anni

Nacque a Ferrara l'11 maggio 1896, terzo di sette figli (sei maschi ed una femmina), dal nobile Ermanno Tibertelli e Giuseppina Donini. Il predicato nobiliare che latinizza il nome della città di Pisa, luogo di origine degli antenati e dal quale l'artista trae il suo nome d'arte[1] gli è stato confermato di recente da un decreto ministeriale che ha riconosciuto la sua discendenza da un personaggio storico benemerito del Ducato estense.[2] Tra i discendenti, la scrittrice e pittrice Bona de Pisis de Mandiargues era una nipote (figlia del fratello Leone Tibertelli de Pisis). Filippo si dedica allo studio della pittura inizialmente sotto la guida del maestro Odoardo Domenichini nella sua città natale, perfezionandosi successivamente con i fratelli Angelo e Giovan Battista Longanesi-Cattani. Nel 1916 si iscrive alla Facoltà di Lettere dell'Università di Bologna, dove si laurea nel 1920 con una tesi sui pittori gotici ferraresi, sotto la guida di Igino Benvenuto Supino come relatore. Inizia la sua attività come letterato e critico d'arte, collaborando a molte testate non soltanto locali.[3] L'interesse e la passione per la pittura lo spingono a vivere in varie città come Roma, Venezia e Milano, Parigi e Londra, alla ricerca di nuovi contesti culturali e artistici.

Periodo romano (1919-1924)

A Roma frequenta la casa del poeta Arturo Onofri e incontra Giovanni Comisso, il quale diverrà suo grande amico. Sin dai primi mesi romani inizia a comporre le novelle che confluiranno nella raccolta La città dalle cento meraviglie, editata nel 1923 con in copertina un'opera del concittadino Annibale Zucchini[4]. Nel 1920 espone per la prima volta disegni e acquerelli nella galleria d'arte di Anton Giulio Bragaglia in Via Condotti, accanto alle opere di Giorgio de Chirico. È in questi anni che comincia ad affermarsi come pittore e le sue opere risentono dell'influsso di Armando Spadini. Le storie della Roma del passato, curiosità e scoperte animano de Pisis ed è proprio su questa traccia che compone "Ver-Vert": "un diario impudico di un poeta che andava diventando sempre più un pittore"[5]. Altri scritti anticipano ciò che verrà rappresentato nelle sue nature morte con paesaggi.

Periodo parigino (1925-1939)

Il periodo parigino, iniziato nel marzo del 1925, registra la sua piena maturità artistica. Dipinge en plein air come i grandi vedutisti ed entra in contatto con Édouard Manet, Camille Corot, Henri Matisse e i Fauves. Sono anni in cui realizza alcune tra le sue tele più celebri: "La grande natura morta con la lepre", "Il bacchino", "Natura morta con conchiglie". Temi ricorrenti, oltre alle nature morte, sono i paesaggi urbani, nudi maschili e immagini d'ermafroditi. In seguito a una mostra personale a Milano nel 1926 presentata da Carrà alla saletta Lidel, raggiunge il successo anche a Parigi con la sua personale alla Galerie au Sacre du Printemps con la presentazione di de Chirico[6].

Nonostante la sua produzione sia legata principalmente a Parigi, continua a esporre anche in Italia e inizia a scrivere articoli per L'Italia Letteraria e altre riviste minori. Stabilisce un rapporto intenso con il pittore Onofrio Martinelli, già incontrato a Roma. Tra il 1927 e il 1928 i due artisti dividono anche una casa-studio in rue Bonaparte. Entra nel circolo degli artisti italiani a Parigi, un gruppo che comprendeva de Chirico, Alberto Savinio, Massimo Campigli, Mario Tozzi, Renato Paresce, Severo Pozzati, e il critico francese George Waldemar (che nel 1928 cura la prima monografia su de Pisis). Durante gli anni di vita a Parigi visita Londra per tre brevi soggiorni, stringendo rapporti d'amicizia con Vanessa Bell e Duncan Grant.

Rientro in Italia (1939-1947)

Casa di de Pisis a Venezia dove visse dal 1943 al 1949

Nel 1939, dopo un soggiorno a Londra, che gli serve per allargare il mercato, rientra in Italia stabilendosi a Milano. In occasione del Premio Saint-Vincent, passa un'estate nella cittadina valdostana dove ha anche l'occasione di incontrare il pittore locale Italo Mus. Si sposta in diverse città italiane: alla Galleria Firenze di Firenze, alla fine del 1941, viene organizzata la mostra "Filippo de Pisis" che comprende sessantuno oli dipinti dal 1923 al 1940.

Nel 1943 si trasferisce a Venezia, dove si lascia ispirare dalla pittura di Francesco Guardi e di altri maestri veneziani del XVIII secolo. Partecipa alla vita culturale della città lagunare, dove stringe amicizia e diviene maestro del pittore ferrarese Silvan Gastone Ghigi, oltre che del pittore, critico e mercante d'arte Roberto Nonveiller. Alla fine dell'aprile 1945, decide di organizzare, nel giardino del suo studio di Venezia, una serata musicale, invitando decine di uomini bellissimi, i cui corpi, coperti solo da gusci di granceola, sarebbero stati dipinti dal vero. Tra gli invitati solo due donne, la scultrice Ida Barbarigo Cadorin e la critica d’arte Daria Guarnati. L'evento viene interrotto bruscamente poco dopo il suo inizio, quando un gruppo di partigiani comunisti irrompe nel palazzo grazie a una "soffiata". Accusati di "mollezza borghese", i partecipanti seminudi, con torso e volto dipinti, sono subito arrestati e scortati in questura dai partigiani, prima di subire un interrogatorio serrato alternato a scherni e reprimende. Alcuni vengono rilasciati, altri no: de Pisis è trattenuto per due notti in camera di sicurezza con una dozzina di delinquenti comuni. Prima della scarcerazione gli viene intimato di non organizzare più "orge del genere"[7].

Dopo un breve soggiorno a Parigi tra il 1947 e il 1948, in cui lo accompagnò l'allievo Silvan Gastone Ghigi, rientrò in Italia con i primi sintomi di una malattia che lo condurrà alla morte. La XXIV Esposizione internazionale d'arte di Venezia, la prima del dopoguerra, gli dedicò una sala personale con trenta opere dipinte dal 1926 al 1948. Si parlava anche di una candidatura al Gran Premio ma un telegramma da Roma ne proibì il conferimento perché omosessuale[8]. L'onorificenza verrà assegnata a Giorgio Morandi.

Similar objects

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

This object was featured in

How to buy on Catawiki

1. Discover something special

2. Place the top bid

3. Make a secure payment